For Your Healthcare Provider

Have your patient scan this QR code with their smartphone camera to instantly access this educational guide on their device.

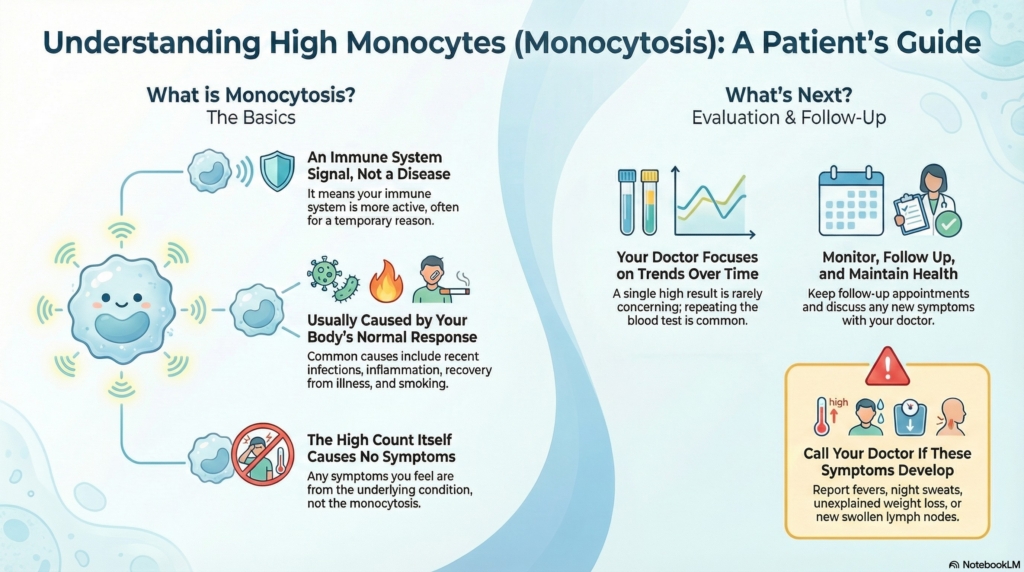

A guide for patients with elevated monocyte count

Access the Resources

Note: The video and audio linked above were generated with the assistance of AI. Clinical accuracy has been reviewed, but no AI-generated content can be guaranteed to be fully error-free.

Monocytosis means you have more monocytes (a type of white blood cell) than usual. This is a common finding and often reflects your immune system responding to something temporary, such as a recent infection, inflammation, recovery from illness, or smoking.

Your doctor looks at your symptoms, recent health events, and whether the number changes over time to understand what it means for you. Most people with monocytosis feel completely well, and the count returns to normal once the underlying cause resolves.

This guide applies to outpatient evaluation and does not apply to emergency or rapidly worsening illness.

First things first

Seeing a higher monocyte count on your CBC is common. Monocytes often increase for simple reasons, such as recent infections, inflammation, or recovery from illness. Your doctor will typically recheck your blood count in a few weeks to a few months to see whether the elevation has settled or is still present. A single elevated value almost never gives the full story, and many temporary elevations return to normal on their own.

Some common recent events that can raise monocytes include:

- recent cold or flu

- recent COVID-19 or other viral infection (even if mild)

- recovering from surgery or dental procedures

- recent injury or trauma

- starting or changing certain medications (including steroids)

- a flare of an autoimmune or inflammatory condition

If you can connect your elevated monocytes to one of these events, it is more likely to be a temporary immune response.

What are monocytes?

Monocytes are a type of white blood cell that help defend your body. They circulate briefly in the bloodstream, then move into tissues where they become macrophages, cells that help clean up debris, fight infections, support healing, and regulate immune responses.

What is monocytosis?

Monocytosis means your monocyte count is higher than the normal range. Labs may define this using either:

- a monocyte percentage above the normal range, or

- an absolute monocyte count (AMC) above about 0.8–1.0 × 10⁹/L (exact cutoffs vary by lab)

Monocytosis is a lab finding, not a disease by itself. It is a clue that the immune system is more active than usual and helps your doctor look for the underlying reason.

How monocytes are measured

Monocytes are counted as part of the CBC differential. The automated analyzer measures:

- the percentage of monocytes among all white blood cells

- the absolute monocyte count (AMC), calculated by multiplying the total white count by the monocyte percentage

The AMC is the more reliable number when evaluating monocytosis.

Ranges that matter

Monocytes are counted as part of the CBC differential (the white cell breakdown). The report typically includes:

- the percentage of monocytes among all white blood cells

- the absolute monocyte count (AMC), calculated from the total white count and the monocyte percentage

The AMC is generally the most useful number when evaluating monocytosis.

Why it happens (causes)

Common outpatient causes of monocytosis include:

- recent infection, especially viral or bacterial

- recovery phase after an illness

- inflammation, including autoimmune conditions

- stress on the body, such as surgery or trauma

- smoking, which can raise certain white blood cell types

- some medications, including steroids

- chronic infections (less common in high-resource settings)

Smoking is a very common cause of mild, persistent monocytosis. If you smoke, this alone may fully explain a mild, stable elevation.

Bone marrow disorders, including certain leukemias, are uncommon causes of monocytosis and almost always come with other abnormal blood counts (such as very high or very low white cells, anemia, or low platelets) and significant symptoms. Isolated monocytosis without other concerning findings is rarely due to these conditions.

Does it cause symptoms?

Monocytosis itself does not cause symptoms. Any symptoms you notice usually relate to the underlying condition that raised the monocyte count, for example:

- fatigue during an infection

- joint pain, stiffness, or swelling with an inflammatory condition

Many people have no symptoms at all when monocytosis is found.

Is it dangerous?

Most cases are not dangerous and improve over time.

A higher monocyte count becomes more concerning when:

- it is persistently elevated, especially beyond about 3–6 months

- it rises over time

- it occurs along with other abnormal blood counts

- you develop symptoms such as fevers, night sweats, weight loss, swollen lymph nodes, or a feeling of fullness under the left ribs

Your doctor looks at the pattern over time, other blood results, and your symptoms to decide whether more testing is needed.

How your doctor evaluates it

Evaluation usually includes:

- reviewing recent illnesses, symptoms, and medications

- asking about smoking and steroid use

- checking for signs of inflammation or infection

- repeating the CBC to see if the elevation persists or improves

- focusing on trends rather than relying on a single result

If you feel well and have no other concerning findings, your doctor may recheck your CBC in 4–8 weeks. If the count is still elevated but stable, another check in a few months is common. Additional testing is more likely if monocytosis:

- persists beyond about 3–6 months

- is rising over time

- is accompanied by other abnormal blood counts

- is associated with new or worsening symptoms

How is it treated?

There is no direct treatment for monocytosis itself. The focus is on identifying and managing the underlying cause.

Most people do not need medication or procedures specifically for monocytosis. If treatment is needed, it targets infections, inflammation, or other conditions driving the higher count.

Daily life and self-care

Most people do not need lifestyle restrictions because of monocytosis.

Helpful steps include:

- monitoring for new or changing symptoms

- keeping follow-up appointments so your doctor can recheck blood counts

- taking medications as prescribed for any underlying condition

- maintaining general health habits (sleep, nutrition, activity)

- if you smoke, considering discussion of smoking cessation with your doctor

No special diet, activity restriction, or infection-control precautions are required solely because of monocytosis.

When should I contact my doctor?

Contact your doctor sooner if you develop:

- fevers, chills, or night sweats

- unexplained weight loss

- new or worsening fatigue

- swollen lymph nodes or fullness under the left ribs

- repeated or hard-to-clear infections

- persistent or worsening abnormalities on repeat blood tests

What is the usual plan going forward?

Many people see their monocyte count return to normal over time as the triggering condition improves.

Your doctor will:

- repeat your CBC as needed

- look for reversible or obvious causes

- decide whether further testing is warranted based on symptoms, trends, and other blood count changes

Most cases require only monitoring and follow-up, not aggressive intervention.

Making sense of it

Think of monocytes as emergency responders who arrive after a problem to clean up and repair.

When there has been an “incident” in the body, like an infection, injury, or inflammation, more responders show up to handle the cleanup.

Seeing more responders does not, by itself, tell you whether the original incident was small or serious, so your doctor looks at the whole picture and whether those responders are still there weeks later.

Monocytosis means your immune system is more active than usual. It is a lab finding, not a disease by itself. For most people, it is temporary and harmless, and the count settles once the underlying cause, such as infection, inflammation, or smoking, improves.

Key takeaways

- monocytosis is common and usually temporary, often related to recent infection, inflammation, recovery, or smoking

- no symptoms from the count itself, symptoms come from the underlying condition, not the monocyte number

- trends matter most, a single elevated result is rarely concerning

- persistence matters, counts that stay high for months deserve a closer look

- follow-up is usually simple, often just repeat CBC testing over time

- call if concerning symptoms develop, especially fever, night sweats, weight loss, swollen nodes, or repeated infections

For clinicians: Read our detailed guide on how to communicate about monocytosis to patients.