A guide for patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance

Access the Resources

Note: The video and audio linked above were generated with the assistance of AI. Clinical accuracy has been reviewed, but no AI-generated content can be guaranteed to be fully error-free.

MGUS can sound alarming, especially when you first see the words “monoclonal protein” on a lab report.

Many people learn about MGUS only because blood tests were ordered for another reason, and the finding can feel unexpected. MGUS is common, especially as people get older, and most people never develop a serious blood disorder from it. Your doctor will explain what the protein means, why follow-up matters, and how monitoring keeps you safe.

This guide applies to MGUS found in outpatient, non-urgent settings and does not apply to patients with symptoms concerning for myeloma, rapidly changing labs, or emergency presentations.

First things first

MGUS is not cancer. It is a slow-moving condition in which a small, stable group of plasma cells makes a measurable protein in the blood.

MGUS is often found by accident during routine blood work.

Most people with MGUS feel well and require monitoring rather than treatment.

What is MGUS?

MGUS occurs when a population of plasma cells produces a monoclonal protein (M-protein).

Unlike cancerous plasma cells, the MGUS cell population does not behave like a cancer and often stays stable over time.

MGUS becomes more common with age and is found in several out of every 100 older adults.

Why it happens (causes)

Doctors do not know the exact cause of MGUS. Contributing factors may include:

- an age-related change in plasma cells

- chronic immune activation from repeated infections or inflammation

- a possible genetic susceptibility

No lifestyle factor is known to cause MGUS.

Does it cause symptoms?

MGUS itself does not cause symptoms.

If you are feeling unwell, this usually relates to another condition rather than the monoclonal protein.

If MGUS ever progresses, symptoms would relate to that new disorder rather than MGUS itself.

Is it dangerous?

MGUS carries a low annual risk of progression to a related condition, such as myeloma or lymphoma.

Most people never progress, and for those who do, changes are usually very slow over many years or decades.

Your individual risk depends on protein type and level, as well as other laboratory markers.

How your doctor evaluates it

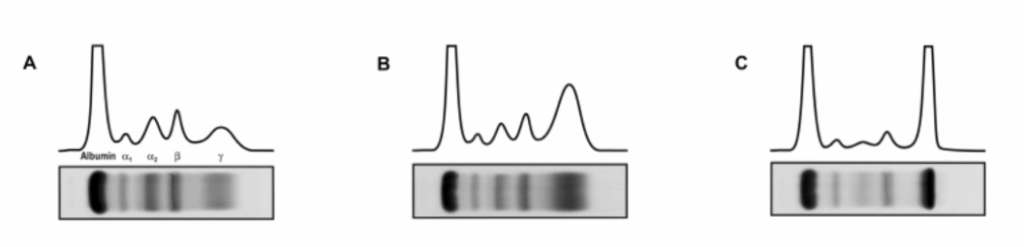

Your doctor tracks MGUS using blood tests that measure the M-protein, which is a small, extra amount of one type of immunoglobulin (antibody). Immunoglobulins are normal proteins your immune system makes, and in MGUS one of them is produced a little more than usual. This creates a small “spike” on a blood test called a serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP).

Most of the follow-up is based on simple blood work, including:

- the M-protein level

- light chain ratio

- kidney function, calcium, and blood counts

For most people, blood tests are the main tool, and a bone marrow biopsy is not usually needed unless something changes or the initial results are more concerning.

How is it treated

MGUS does not require treatment because the abnormal cells are not harmful on their own.

Treatment begins only if progression occurs, such as development of myeloma-related findings.

Daily life and self-care

Most people with MGUS can live their usual lives without restrictions.

There are no special diets or supplements proven to affect MGUS.

General wellness — exercise, sleep, limiting alcohol, and not smoking — supports overall well-being.

When should I contact my doctor?

Contact your doctor if you have:

- new bone pain

- unexplained fatigue

- repeated infections

- new numbness or tingling

- changes in your labs reported elsewhere

What is the usual plan going forward?

Most people with MGUS are seen once or twice per year, depending on the protein level and other risk factors.

Your doctor will focus on regular follow-up, checking stability, and adjusting visits if anything changes.

Making sense of it

MGUS is like a small, quiet signal on a radar screen.

It does not cause harm by itself, but the radar helps us watch for changes over time.

MGUS means a small group of plasma cells is making a steady protein.

Most people stay stable for life.

Regular monitoring keeps you safe.

Key takeaways

- MGUS is not cancer; it is a slow-moving condition.

- risk of progression is low (on average about 1 in 100 people per year).

- monitoring is usually all that’s needed for most people.

- call if symptoms change or new symptoms appear.

For clinicians: Read our detailed guide on how to communicate about MGUS to patients.