The mind is the real instrument of sight and observation, the eyes act as a sort of vessel receiving and transmitting the visible portion of consciousness (Pliny, the Elder 1st c. A.D.)

Perception is the gateway to our understanding of our world (E. Bruce Goldstein).1

Perception of the field of medicine has changed in the last fifty years. So has that of the doctor and the doctor-patient relationship, the core of medical practice since Hippocratic times. The reasons have been well articulated elsewhere but chief among them has been a neo-liberal agenda of competition and ‘progress,’ consumerism, managerialism, medical litigation, and the dominance of a scientific model of knowledge based primarily on research. However, Dr. Seamus O’Mahony, an Irish gastroenterologist, claims that there is a problem with scientific research. In Can Medicine Be Cured: The Corruption of a Profession (2019), he outlines the case that since the 1980s, medical research has become a global business and the driver of the medical-industrial complex. He adds, provocatively, that the majority of medical research is a waste of time and money either because it is badly carried out, or serves the needs of researchers and allied commercial interest [2].2 It is a view that has been corroborated by Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, when he stated that perhaps 50% of findings in medical research could not be duplicated.3 So clearly, there is a problem with too great a reliance on this model.

The exponential growth of technology has exacerbated these issues and led to public distrust of doctors, rising costs, lack of compassion by doctors, and undue pressure and frustration for doctors burdened with budget and treatment targets, guidelines, quantitative measurement, and conditions better suited to running a business rather than a health service. It became clear that there was a crisis in healthcare and something needed to be done.

Many medical schools in the United States, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Europe, tried to counterbalance the above forces by attempting to rediscover the values of caring and compassion through the medical humanities. As Dr. David Nathan remarked, “…if you’re going to be a doctor, you’re going to see people from all walks of life and in your personal experience you can’t know people from all walks of life. You’re going to learn more from James Joyce, than you are from your own experience…I read…the great novelists…and from them I learnt about people”.4 In other words, through the arts, it is possible to have experiences vicariously, through the imagination, that one could not have in reality.

Experience, we know, is central to growth and as a medium of education that expands consciousness. The influential American pragmatist psychologist/philosopher, John Dewey (1859-1952), wrote that art is also a mode of human experience.5 He noted, however, that it requires apprenticeship, time, to see through a microscope or to see a landscape as a geologist sees it. It is a similar with perception: the more one looks, the more one sees. Artist Paul Cèzanne once said: “Time and reflection gradually modify vision, and at last comprehension comes”. Yet, perception is far from a passive, reflexive process as Dewey observed: “…to perceive, a beholder must create his own experience.”6

The basis of art, but also of science and medicine, is curiosity in order to devise new ways of looking at the world. To do this, thinking itself has to be liberated from a mechanistic, reductive process in favor of one that encourages creativity, collaboration, and critical thinking. The arts can provide a path to achieving this. At a cognitive level they can provide a way of knowing not experienced before; liberate us from the literal; enable us to step into the shoes of others; tolerate ambiguity; explore what is uncertain; help exercise judgment free from prescriptive rules, and direct attention inwards to what we feel or believe.

When asked in 2008 by Trinity College Dublin’s School of Medicine if I would like to participate in the newly inaugurated medical humanities modular programme, I decided to link my twenty-year medical experience with that of art history training and teaching. Searching for that link led me to realize that there were many overlapping, yet little appreciated, points of confluence between the two disciplines. Both begin in close observation, progressing step-by-step to take account of context, history, time, and physical examination to arrive at a tentative diagnosis or narrative. Both processes depend primarily on the doctor’s or art historian’s perception. This in turn is a complex matter informed by one’s cultural background, knowledge, experience, memory and worldview, each of which is open to change over time. As William James (1842-1910), the American pragmatist psychologist and philosopher put it, perception is not simply what we take from the world, but what we make of it: “Whilst part of what we perceive comes through our senses from the object before us, another part (and it may be the larger part) always comes out of our own mind.”7

“Perception in Medicine and Art”, the title of the module, drew on a number of sources, some already mentioned, which informed the structure and thinking of the module. While the arts are often seen as intellectually undemanding and emotional, the view taken was that this is far from the case. The arts involve a transformation of consciousness through perception which is a process shaped by culture, language, beliefs, values and individual sensibility. And, as James pointed out, the sensory system becomes an extension of the mind. The difference behind recognizing something and perceiving it is fundamental. Recognition is where a percept is merely given a label, whereas perception requires exploration and further experience. To find meaning in images, whether medical or artistic, requires acquiring a set of skills that move from simple identification to a complex interpretation based on context, psychology and philosophy. Thus, like a child learning to read a book, “reading” a medical or art image takes time.

Abigail Housen’s research on Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) also informed the module. In her paper entitled “Aesthetic Thought, Critical Thinking and Transfer”, she outlined the results of a five-year longitudinal study in school children which showed that viewing art led to a transfer of critical thinking skills. 8 Visual literacy (finding meaning in images), as mentioned, involves a set of skills that moves from simple identification to interpretation on contextual, metaphoric, psychological and philosophical levels. Learning to see requires time, exposure and education. While growth is related to age, it is not determined by it. Thus, an adult will not automatically be at a higher level of aesthetic development than a child.

Housen formulated five stages of aesthetic development from her extensive research: Stage 1: viewers are storytellers using memories, personal associations, and observation of the work, making a judgment based on what is known and liked. Stage 11: viewers start building a framework using their perceptions, knowledge and values. Stage 111: viewers adopt an analytical and critical stance like an art historian. Stage IV: interpretive viewers explore the work and appreciate subtleties of line, shape, colour. Stage V: experienced viewers combine personal contemplation with broadly universal concerns. Interestingly, Housen found that most interviewees, even frequent museum visitors, fell between Stages 1 and 11. Thus it was assumed that most first-year medical students would also fall into these categories.9

A chance encounter at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 2006 was another defining moment. While attending a conference on the arts in health, I heard art historian /lawyer, Amy Herman, then arts educator at the Frick Museum of Art, New York, describe how she used images from the Frick Collection to teach medical students to look closely and communicate better to improve their visual intelligence. 10 She subsequently used the programme with New York police officers, the FBI, State Department, Fortune 500 Companies and the U.S. military. Speaking to her afterwards, I realized that with my dual background, I could do something similar, using medical and art imagery interchangeably. 11

My experience of receiving two contrasting kinds of education, in medicine and art history, was also critical to my thinking about this module. In the 1960s and 1970s, medical training involved a scientific, rational analytical approach to the body and disease, but at the same time the place of the time-honored clinical history and examination of a patient was still a central component. One could argue that this was probably the golden era of modern medicine where scientific advances could be applied to patient care, yet, clinical diagnosis was still valued and respected, often in the absence of ‘tests’. It was implied and understood, that clinical medicine required more than rationalism and doctors were part of a learned profession rather than vocationally trained practitioners. Moving to study the arts in the 1990s was a joyous experience as it opened up other fields of knowledge and human experience which involved history, art, philosophy, psychology, literature, cultural theory, and politics. This was a different approach with its own scientific tools of qualitative analysis as opposed to the quantitative one of science and with a broader view of knowledge that could not be reduced to mathematical verification.

The Module

Beginning with a pilot in 2008, all first-year medical students from Trinity College Dublin (TCD) could choose from thirteen Student Selected Modules (SSM) (Fig. 1). These are compulsory since 2010. “Perception in Medicine and Art” takes a maximum of twelve students. No prior knowledge of art is required. The themes that loosely inform the module are: 1) looking and seeing; what are you looking at: is this a radiograph, patient image, painting, photograph, sculpture or print? 2) seeing and believing; 3) what might lie beneath the surface? 4) what is happening outside of the painting and how do you know from observation alone? For example, where is the light coming from? 5) body language and gesture and what it tells us; 6) how does the artist gain our attention? 7) how does color affect the work? 8) what possible narrative (s) can you apply to the work?

The six-week three hourly module is completely interactive (and playful) with no preparation required. Students work on the spot, and never know from one week to the next what to expect. This is designed to heighten expectation and collaboration. Besides discussion, classroom activities comprise looking closely at medical and art imagery, videos, films and small exercises in perception and memory. The latter involves getting students to sit back-to-back, then briefly describe the colleague behind them (for example, hair color, eyes, clothes, and shoes). These are then read out, usually to laughter, as errors of description are often made, showing the fallibility of memory. A discussion follows of the difference between a glance, a stare, a gaze, and the factors that influence looking and seeing, including attention, memory, knowledge, and cultural background.

Classroom activities are augmented by trips to nearby art galleries in which an initial discussion takes place as to the meaning of the architecture, and the variety of reasons why artworks find their way into the gallery. The group is divided into pairs and put in front of pre-selected paintings to look at carefully. Each pair then present their findings to reassembled colleagues, as if on a ‘ward round’ in hospital in which they offer a tentative narrative (diagnosis) based on an accurate description of what they see. Each statement must be qualified, for example “why do you say that man is old?” The painting thus plays the role of proxy for a patient.

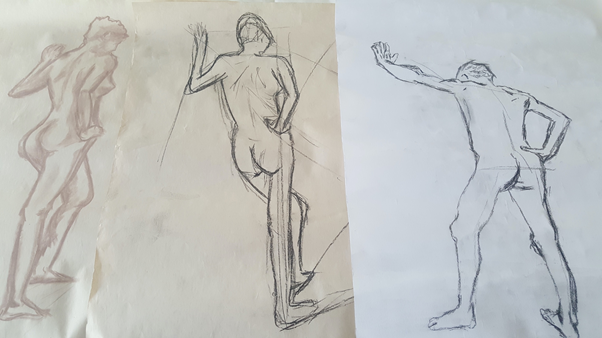

Another aspect of the module involves the students becoming art students as they learn to draw from the life model, taught by a practicing artist. This is designed not only to slow down the looking process but also to get a sense of themselves looking, as well as seeing the human body from the different perspective of an artist (Fig. 2). They learn through drawing that the perspective of the body changes as it moves through space. This makes a great impression on many as concurrently in their medical classes they are dissecting cadavers.

Another popular part of the module is done in cooperation with the education staff of the National Gallery of Ireland, located beside Trinity College. Here the role of the sense of touch used by the blind and partially blind to ‘see’ is the focus. The blindfolded students learn to feel their way by touch around a pre-treated painting from the collection with raised lines and contours (Fig. 3). They are then brought to view the particular painting in the gallery and are often surprised at the difference of their conception of the work and the reality. Other activities include visits to an artist’s studio, a conservation laboratory, or particular exhibitions.

At the beginning of the course, students fill out a simple questionnaire about why they chose the module and what they expected. They are also given a medical and art image and simply asked to list briefly what they see. A similar procedure takes place at the end of the course. Once again, a medical and art image are described, this time usually with greater accuracy. Finally, students may choose any artwork they wish, to write a short descriptive analysis, using a basic art vocabulary, supplemented by their own drawing. Very often, with the drawing, other aspects of the work are discovered which were missed on earlier viewing. An annual exhibition with prizes takes place for all of the modules at the end of term and the medical school collects student reflections on each course. The following are a selection for “Perception in Medicine and Art”.

This module made me think outside of the box and allowed me to venture outside my comfort zone. Because of this, I think this module was very beneficial to me!

This module opened my eyes to see the world in a different way. How I can tie art in my life as I progress my journey in medicine.

I am more observant and find myself more drawn to looking into the links between art and medicine. Life as a student can be very fast paced and this module definitely taught me to take the opportunity to stop and just be aware of everything going on; it’s easy to miss the big picture when you’re caught up in the details.

As I hope is clear, this module’s approach could be used in many areas both inside and outside of medicine. But in relation to haematology specifically, it would find a place in both the clinical diagnosis of patient signs and the analysis of blood smears.

About the author

Brenda Moore McCann received her M.B. at University College Dublin and was medical director of a non-governmental agency, Family Planning Services, before taking a Diploma in the History of European Painting at Trinity College Dublin followed by a B.A. (Mod) in Art History and Classical Civilisation and a Ph.D. in Art History. Click here to learn more.