For Your Healthcare Provider

Have your patient scan this QR code with their smartphone camera to instantly access this educational guide on their device.

A guide for patients with elevated hemoglobin or hematocrit

Access the Resources

Note: The video and audio linked above were generated with the assistance of AI. Clinical accuracy has been reviewed, but no AI-generated content can be guaranteed to be fully error-free.

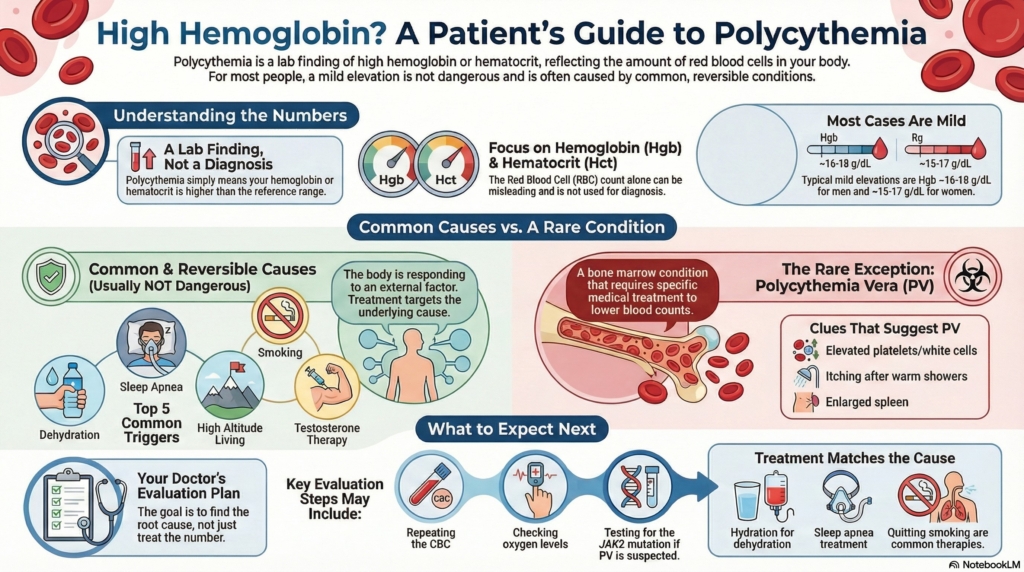

Seeing a high hemoglobin or hematocrit on a blood test can be worrying.

Most mild elevations are not dangerous and usually reflect common, reversible causes such as dehydration, sleep apnea, smoking, testosterone, or living at altitude, rather than a blood cancer. You may see the terms “erythrocytosis” or “polycythemia” used, but for practical purposes the key values are your hemoglobin and hematocrit. Your doctor will explain what your numbers mean, whether they are changing over time, and what follow-up is needed to keep you safe.

This guide is intended for outpatient evaluation of elevated red blood cell levels and does not apply to emergency situations, ICU care, or acute conditions such as severe hypoxia, dehydration, or suspected polycythemia vera crisis.

First things first

Seeing a high hemoglobin or hematocrit can be worrying, but most mild elevations are not dangerous and do not mean cancer. Many common conditions—such as dehydration, sleep apnea, smoking, or living at altitude—can temporarily or chronically raise these values.

The key is understanding how high the numbers are, whether they are changing over time, and whether the rest of your CBC is normal.

What are hemoglobin and hematocrit?

Hemoglobin and hematocrit are the two main markers used today to define polycythemia.

- hemoglobin (Hgb) is the concentration of the oxygen-carrying protein inside red blood cells

- hematocrit (Hct) is the percentage of your blood made up of red cells

These two measurements reflect your red cell mass, which is the true basis for defining polycythemia.

Although red cell mass can be measured directly, it is no longer done in routine practice, so hemoglobin and hematocrit are used instead.

Why not use the red blood cell count?

The red blood cell count (RBC) can be misleading.

It may be high even when hemoglobin and hematocrit are normal—for example, in:

- thalassemia trait

- iron deficiency with very small red cells

This pattern is called erythrocytosis, and does not mean polycythemia.

For diagnosing polycythemia, hemoglobin and hematocrit are what matter.

What is polycythemia?

Polycythemia means that the hemoglobin or hematocrit is higher than the laboratory’s reference range.

It is a finding, not a diagnosis.

Most people with an elevated hemoglobin or hematocrit do not have a bone marrow disease.

You may see the terms “erythrocytosis” and “polycythemia” used interchangeably, but doctors focus on hemoglobin and hematocrit when deciding what evaluation is needed.

How hemoglobin and hematocrit are measured

On your CBC:

- hemoglobin is reported as g/dL

- hematocrit is reported as %

Your report may show:

- values marked in red

- comments such as “polycythemia” or “erythrocytosis”

- normal platelets and white blood cells (very common in benign causes)

Ranges that matter

Typical thresholds used in adults:

- mild elevation:

Hgb ~16–18 (men), ~15–17 (women) - marked elevation:

Hct >52–56% - very high:

Hct >56% or Hgb >18.5

Most outpatient cases fall into the mild range.

Why hemoglobin and hematocrit go up (causes)

Relative polycythemia

Hemoglobin or hematocrit appears high because the plasma (fluid) part of the blood is low, not because the body has too many red blood cells.

Common triggers include dehydration, diuretics, vomiting, sweating, and acute stress.

The red cell mass is normal, and levels often improve with hydration.

- normal red cell mass

- low plasma volume

- dehydration, diuretics, vomiting, sweating, stress

True (absolute) polycythemia

The body is truly making extra red blood cells.

This may occur because of low oxygen, changes in kidney signaling, certain medications or hormones, or (rarely) a bone marrow condition such as polycythemia vera.

- increased red cell mass

- due to ↑ EPO or EPO-independent mechanisms

Oxygen-related causes

Anything that lowers oxygen can signal the kidneys to make more red blood cells.

Examples include:

- sleep apnea

- chronic lung disease (such as COPD)

- obesity-related nighttime low oxygen

- living at high altitude

- some heart or lung conditions

These are among the most common causes of true polycythemia.

Hormones, medications, and metabolic factors

Some therapies or hormonal conditions can raise hemoglobin and hematocrit.

Examples include:

- testosterone therapy

- anabolic steroids

- certain supplements or hormonal regimens

- some medications that shift fluid balance or metabolism

These often cause mild-to-moderate increases.

Kidney-related causes

Your kidneys make a hormone called erythropoietin (EPO), which tells the bone marrow to make red blood cells. Certain kidney-related issues can increase this signal even when oxygen levels are normal.

Examples include:

- kidney cysts or polycystic kidney disease

- renal artery narrowing

- hydronephrosis

- kidney or liver tumors that produce EPO (rare)

These causes are still uncommon but important to recognize.

Rare bone marrow causes (polycythemia vera)

Polycythemia vera (PV) is an uncommon bone marrow condition in which the body makes too many red blood cells without an external trigger.

Polycythemia vera is linked to a change (mutation) in a gene called JAK2, which your doctor can test for.

Clues that make PV more likely include:

- elevated platelets or white cells

- itching after warm showers

- redness or burning of the hands or feet

- an enlarged spleen

- a positive JAK2 mutation

Most people with elevated hemoglobin or hematocrit do not have PV.

Inherited or genetic causes

Rarely, inherited conditions can increase red blood cell production, including:

- high-oxygen-affinity hemoglobins

- changes in the body’s oxygen-sensing pathway

These are uncommon and usually lifelong patterns.

Does polycythemia cause symptoms?

Most people with polycythemia do not have symptoms, especially when the cause is common and reversible (such as dehydration, sleep apnea, smoking, altitude, or hormone-related changes).

Symptoms mainly occur in polycythemia vera (PV), a rare bone marrow condition.

When symptoms are unlikely

In secondary or relative polycythemia, symptoms usually come from the underlying condition, not the elevated hemoglobin itself.

For example:

- sleep apnea → daytime fatigue or snoring

- smoking → cough

- dehydration → thirst or dizziness

The high hemoglobin or hematocrit does not usually cause symptoms on its own.

Symptoms more typical of polycythemia vera

If symptoms do occur, they may include:

- itching after warm showers

- headaches or dizziness

- a flushed feeling

- visual changes

- tingling, burning, or redness in the hands or feet

- fullness in the left upper abdomen (from an enlarged spleen)

These symptoms are much more specific to PV, not to other causes of polycythemia.

Bottom line:

Symptoms depend on the cause, not the number.

Is it dangerous?

For most people, polycythemia is not dangerous, especially when it is due to common, reversible, or physiologic reasons.

Danger mainly arises when the cause is polycythemia vera (PV) or, very rarely, when the hematocrit becomes extremely high in certain congenital heart or lung conditions.

When polycythemia is not dangerous

Secondary or relative polycythemia is usually safe:

- risk of blood clots is very low

- symptoms are uncommon

- the high value is often reversible, such as with sleep apnea, smoking, altitude, dehydration, or hormones

Treatment focuses on the underlying cause, not on lowering the red blood cell level directly.

When polycythemia can be dangerous

Risk increases mainly when the cause is polycythemia vera (PV).

PV can:

- increase the risk of blood clots

- enlarge the spleen

- cause symptoms such as itching, redness of extremities, headaches, or visual changes

- continue rising without a physiologic trigger

Doctors confirm PV with JAK2 mutation testing and sometimes bone marrow evaluation.

Rare exceptions

Occasionally, people with complex congenital heart disease may develop very high hematocrit levels that require specialized monitoring.

These cases are uncommon and are typically managed by a cardiologist.

Bottom line:

Whether polycythemia is dangerous depends on why it is happening, not on the number alone.

How your doctor evaluates polycythemia

Repeat CBC

to confirm the finding and assess trends

Oxygen level or sleep apnea testing

to check for low-oxygen states

Kidney function tests and erythropoietin (EPO) level

to assess kidney-related causes

Iron studies

iron status can affect interpretation

Review of smoking or nicotine use

tobacco and carbon monoxide raise red cell levels

JAK2 mutation testing

to evaluate for polycythemia vera when appropriate based on your overall results

How is it treated

Treatment depends entirely on the cause:

- sleep apnea → treat the apnea

- smoking → quitting lowers red cell levels

- dehydration → hydrate

- hormones or medications → adjust therapy if needed

- kidney-related causes → treat the underlying condition

Phlebotomy and low-dose aspirin are treatments for polycythemia vera. Some people with PV may also need cytoreductive therapy. These treatments are not used for common or reversible causes.

Daily life and self-care

Most people can:

- continue normal daily activities

- stay well hydrated

- avoid smoking or vaping

- monitor symptoms

- complete sleep apnea testing if recommended

Most routine daily activities are safe when hematocrit elevations are not due to PV.

When should I contact my doctor?

Contact your doctor if you have:

- new headaches, dizziness, or vision changes

- unusual bleeding or bruising

- chest pain or shortness of breath

- symptoms of sleep apnea

- rising hemoglobin or hematocrit on repeat testing

Seek urgent care for severe shortness of breath, chest pain, or neurologic symptoms.

What is the usual plan going forward?

Most people need:

- periodic CBCs

- evaluation for reversible causes

- monitoring of oxygen levels or sleep studies, when appropriate

- lifestyle guidance related to smoking, hydration, or sleep apnea

Many patients do very well once the cause is identified.

Making sense of it

Imagine your red blood cells as delivery drivers carrying oxygen throughout the body. Sometimes the body calls for a larger fleet, for example, at high altitude, with low oxygen at night from sleep apnea, or when the kidneys signal that more drivers are needed. The bloodstream looks busier because your body thinks it needs extra help, not because something is wrong with the cells themselves.

A higher red blood cell count (erythrocytosis) is often the body’s response to a signal, not a disease by itself. In many people, the cause is temporary or related to conditions like dehydration, sleep apnea, lung issues, or smoking. The key is understanding what signal is prompting the body to make more cells.

Your doctor’s job is to figure out whether this extra production makes sense for you, and whether the cause is benign, correctable, or something that needs closer attention.

Key takeaways

- polycythemia means high hemoglobin or hematocrit, not just a high red blood cell count

- most causes are common and reversible, such as dehydration, sleep apnea, smoking, or hormones

- relative polycythemia (low plasma volume) is common and improves with hydration

- polycythemia vera is rare, and testing is done only when appropriate

- evaluation focuses on identifying the cause, and most people need monitoring, not treatment

For clinicians: Read our detailed guide on how to communicate about polycythemia to patients.