Listen: Roots to Rivers — An Audio Companion

An AI-generated narrated version of this essay.

Why Galen Matters

Modern medicine is built on measurement and mechanism, yet it still depends on imagination. The metaphors we use to think about the body, whether networks or circuits or codes, shape what we believe life to be. Galen matters because he reminds us that this has always been so. A Greek physician of the second century, working at Rome and writing across anatomy, philosophy, and theology, he lived in a world where those disciplines were not divided. His writings stand at a crossroads where physiology, philosophy, and theology were one conversation, and where the study of the body was inseparable from the search for meaning.

Galen was also the most accomplished anatomist of antiquity, and he regarded anatomical structure not only as the foundation of medical practice but as a window into the purposive order of Nature.[efn)_note]May describes Galen’s anatomical works as “comprehensive, logical… far better organized than the other treatises of his time… clear, detailed, sometimes brilliant,” written by an anatomist who “has seen and studied again and again what he is describing” and who brought “no little” contribution to anatomical knowledge.[/efn_note] His importance is vast: he shaped medical thought for centuries, integrated empirical observation with philosophical reasoning, and developed a physiology that joined organic process to moral order. But he also left something more subtle. He showed that scientific understanding is inseparable from the language that expresses it, and that metaphor can be an instrument of knowledge rather than a rhetorical flourish.

This essay explores one dimension of Galen’s work: how his metaphors of roots and rivers, cities and aqueducts, workshops and living fires, organize his understanding of blood formation and vascular flow. These are not the only domains where he thinks in images. Galen deploys metaphor throughout his medicine—in digestion, respiration, neurology, embryology, pathology, and even therapeutics. His physiology is knit together by a network of analogies that illuminate structure and purpose across the whole body. Here, however, I concentrate on the vascular system not because it is the sole arena of his metaphoric reasoning, but because it reveals that reasoning with exceptional clarity. In the vessels that form, branch, and flow, Galen shows most vividly how metaphor becomes a mode of explanation.

Galen the Anatomist: Seeing and Knowing

Before one can understand Galen’s metaphors, one must understand what he saw. Galen was not simply a reader of texts or an inheritor of doctrines. Galen was not only a prolific writer; he was an anatomist whose technical skill and observational discipline shaped every aspect of his physiology. His understanding of the body was grounded in the physical labor of dissection and vivisection, not merely in inherited doctrine. He learned by opening bodies, handling organs, and following vessels with his fingers, and his metaphors arise from that tactile, empirical practice.

Galen offered remarkably practical instructions for exposing the vascular system. To observe the delicate epigastric veins beneath the abdominal skin, he recommended dissecting animals with little subcutaneous tissue and while the blood still remained in them. Fine vessels of the mesentery could be revealed, he explained, by compressing the larger veins upstream, “filling the smaller ones with blood” so that they stood out against the membrane. He advises the anatomist to use the fingers rather than the knife to peel apart the vessels of the liver and lungs, preserving their branching pattern for study.

His experiments show a careful control of physiological conditions. The heart must be exposed in a warm room, such as a bath-house, because cold air disturbs its natural rhythm. Hemorrhage must be anticipated and mastered: the left hand is to be placed so as to clamp the spurting artery before the anatomy can be examined. Once exposed, the heart can be grasped with the fingers or with forceps to observe how its motion changes, and when removed entirely from the chest it continues to beat long enough for its cavities, valves, and great vessels to be studied as if in a living diagram.

Galen’s anatomical work extended beyond dissection. He cut and ligated arteries in two places and then opened the segment between the ligatures, demonstrating that arteries contain blood rather than air. He pierced vessels with fine knives and reeds to watch blood empty from them and inserted hollow tubes into exposed arteries to understand the mechanism of the pulse. He poured hot and cold water over exposed hearts to study the effects on their contractions. His observations were not accidental but systematic, guided by a disciplined sense of how to produce the conditions that made physiological action visible.

Although he was barred from human dissection, Galen refined his understanding by examining wounded gladiators, soldiers injured in battle, and patients with traumatic openings that exposed internal structures.1 He studied apes to prepare for the rare opportunity to dissect a human body, regarding them as the closest anatomical analogues to humankind. He compared species not only to note differences but to identify universal patterns, inferring the common principles of organ function from the shared structures of red-blooded animals.2

This is the world from which Galen’s metaphors emerge: a world of exposed vessels, compressible channels, living heat, pulsating organs, and tissues that can be filled, emptied, or illuminated at will. His analogies are not speculative images but conceptual distillations of what he had cut open, manipulated, and held. To follow Galen’s metaphors, therefore, is to follow his hands. It is to see how the anatomist who worked in flesh transformed the observation of nature into images that think. Even the most ordinary features of structure confirmed for him that Nature builds with foresight. The roundness of arteries and veins, which he judged least susceptible to injury,3 the denser arterial coats that guarded volatile pneuma,4 the looser venous walls that allowed heavy blood to seep into surrounding parts, and even the “mouths” by which certain arteries seemed to breathe through skin or intestine—all of these observations made form appear already half metaphorical, predisposed to the images that would later organize his physiology.

Galen and Metaphor

As Heinrich von Staden observes, Galen was acutely aware that one of the chief hazards facing science lies in its dependence on language: the physician cannot do without words, yet words continually threaten to betray the precision that science demands. Galen therefore reflects repeatedly on the relation between scientific knowledge and the language that seeks to express it, even devoting treatises to questions of terminology and style. His concern with language extends across more than twenty surviving works, from linguistic and logical writings to anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology, and includes a sustained discussion in On the Differences of the Pulse, where he pauses amid technical exposition to consider how figurative language can both clarify and mislead, and why the physician must employ it with deliberate restraint.

For Galen, however, language is not merely a tool but an impulse. As Ben Morrison notes, Galen believed that speech arises from an innate human desire to share understanding, even as he lamented that he “wished he could both learn and teach things without the names for them.”5 His reflections on language and naming have received significant scholarly attention, especially his concern with precision, definition, and the limits of terminology. Although Galen’s reflections on language and terminology have received sustained attention, his use of metaphor as a mode of scientific explanation remains surprisingly underexamined. This is particularly true in the domain of physiology, where his images of roots, rivers, aqueducts, and cities illuminate how he understood blood formation and vascular flow. These metaphors are not rhetorical embellishments but instruments of thought, revealing how figurative language participates in his physiology of purpose.

Galen’s theory of language cannot be separated from his conception of scientific reasoning. Like demonstration in logic, speech must proceed from clear and agreed-upon first principles.6 For him, the supreme virtue of scientific diction is clarity, saphēneia. Metaphor is admissible only when it serves that clarity, either as a necessary resort when literal expression fails or as a shortcut for the trained mind, a gesture that indicates rather than elaborates. Crucially, such metaphors do not belong to the realm of sophistry or ornamental rhetoric that Galen so often condemns; they operate within the same rational enterprise as definition and demonstration. The disciplined use of metaphor thus parallels the discipline of demonstration. Both aim to illuminate the structure of nature without distorting it.

Galen’s metaphors must also be understood against the backdrop of his method of discovery. He held that knowledge arises from the joint operation of reason and experience, neither of which is sufficient alone. Demonstration required properly chosen premises, some evident to the senses and others grasped by the intellect, each tested and refined through repeated observation. His ideal of proof was geometric, a method that moves from secure starting points toward necessary conclusions. Yet Galen also acknowledged the limits of strict demonstration, especially in physiology, where many processes cannot be directly observed. In such cases he allowed the guidance of final causes and employed metaphors as clarifying instruments, images that reveal the structure of a problem when neither sense perception nor logic alone can resolve it. His insistence on defining terms, his refusal to quarrel over names, and his commitment to organizing experience through reason all shape the metaphors he permits. They do not decorate the argument; they disclose the relationships that make demonstration possible.

The ascent of understanding continues beyond literal precision. As von Staden and R. J. Hankinson note, the scientist must move from mere naming toward definition, the horos, which expresses the structure and essence of the thing. In this progression, metaphor gives way to literal naming, and literal naming to definition. Language becomes a ladder toward knowledge, each rung refining thought until it reaches the level of demonstrative science.7

For all his insistence on precision, Galen recognized that science could never free itself entirely from the figurative habits of thought that shaped its past. Von Staden captures the paradox: “Galen, too, is a master of metaphor,” a writer who must confront “the past army of metaphors with his own army of metaphors.”8 He knew that the errors of earlier reasoning often persist as metaphors, verbal fossils that continue to shape how we imagine nature. His task as both scientist and historian was to unmask these inherited images and to redeem them through disciplined understanding. In this act of linguistic self-correction, Galen saw not only an intellectual duty but a moral one. The pursuit of clarity in language becomes a form of philanthrōpia, the expression of humanity’s capacity for reason and care.

Galen’s use of metaphor thus reveals the unity of his thought. Between literalness and imagination lies a space of disciplined creativity, where analogy serves demonstration and language becomes an instrument of knowledge. To follow his metaphors is to glimpse the deeper conviction that nature, reason, and speech all partake of the same order, and that through careful language the physician may approach the intelligible beauty of the living world.

Table. Galen’s Metaphors for the Body, Blood, and Vessels

| Metaphor | Domain | What It Explains | Interpretive Logic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roots (rhizai) | Botany | Veins drawing nutriment from gut and tissues | Veins behave like roots absorbing sap from earth; nourishment is extracted directly from surrounding material. |

| Rivers | Hydrology | Flow of nutriment and blood through vessels | Veins as distributive channels carrying nutriment outward; no return flow. |

| Aqueducts | Civic engineering | Long venous trunks and the vena cava | Large, protected conduits constructed to deliver life-sustaining material efficiently. |

| City / Polis | Political order | Organization of organs and their interdependence | Body as an ordered civic community with roles, cooperation, and hierarchy. |

| Workshops / Craftsmen | Artisanal practice | Action of natural faculties (attractive, alterative, expulsive, formative) | Nature as artisan; organs craft, refine, and perfect nutriment like skilled workers. |

| Bellows | Metallurgy | Dilation of heart and arteries (diastole) | Expansion creates suction; active widening draws in blood and air. |

| Furnace / Hearth | Elemental physiology | The heart’s innate heat | Heart as a living fire whose heat animates and alters blood. |

| Flame drawing oil | Lampcraft | Upward pull of refined material | Heat causes fine material to rise, illustrating selective attraction. |

| Lodestone / Magnet | Natural philosophy | Selective attraction by “appropriateness of quality” | Organs draw what is akin to themselves, not by pressure but by sympathy. |

| Pores and Sieves | Domestic tools | Invisible openings between arteries, veins, organs | Fluid exchange occurs through minute passages like pores, strainers, or wicker sieves. |

| Dew / Moisture settling | Meteorology | Peripheral nutrition in tissues | Blood’s useful juice condenses like dew over parts, where it is absorbed. |

| Roads and Gates | Civic logistics | Directional movement of nutriment and residues | Pathways guide flow; gates slow, delay, or divert material for proper processing. |

| Brew / Fermentation | Viniculture | Transformation of chyle into blood | Heat ripens material; residues settle (black bile) while light portions rise. |

| Sponge / Sump | Material textures | Action of spleen and loose tissues | Thick residues are absorbed by porous organs designed to draw down and alter dregs. |

| Hearth and Bellows (Lung) | Metallurgy | Lung fanning heart’s innate heat | Lung moderates and supports cardiac fire, preventing overheating. |

| Musical Harmony | Music theory | Coordination of faculties and motions | Nature tunes the body like strings of a lyre; concordance produces life. |

Forming the First Vessels: Metaphor, Mechanism, and the Logic of Embryogenesis

Galen’s account of embryogenesis—and especially of what we would now call vasculogenesis and angiogenesis—reveals a remarkable tension between literal mechanism and metaphorical imagination. Nowhere is this more striking than in his description of how Nature fashions the first blood vessels in the embryo.

Galen begins with a material principle and an active principle. Menstrual blood provides the raw substance of generation, “a single uniform matter… like the statuary’s wax,” while the semen acts as craftsman, the shaping and altering faculty that draws this material to itself, assimilates it, and gives it form.⁽¹⁾ The earliest embryo is thus not an inert mixture but an incipient workshop, where the seminal faculty warms, cools, dries, and moistens the material into differentiated parts.

From this starting point, Galen moves to one of his most vivid accounts of how vessels arise:

“The Creator made blood vessels from a certain plastic juice like wax by mingling the moist with the dry… then, breathing through the material and inflating it… made a long hollow vessel, pouring out more of the material when it was to be thick and less when it was to be thin.”⁽²⁾9

The imagery is astonishing: Nature mixes a plastic substance, adjusts its viscosity with heat and cold, and then inflates it like a glassblower forming a tube. Is this metaphor or mechanism?

For Galen the distinction scarcely applies. What may strike a modern reader as metaphorical – the wax, the blowing, the plastic juice – operates for Galen as a literal model of the causal powers at work. In his physiological epistemology, you describe nature’s invisible acts by analogizing them to the most intelligible crafts. Metaphor is not decoration but demonstration by likeness. The “plastic juice” is not meant as a chemical compound but as an intelligible analogy for a stage of matter that is neither fluid nor solid, a substance capable of being thickened, dried, hollowed, or extended. Likewise, Nature’s “breathing” into the material is not respiration but an image for the expansive tension that produces hollow channels, an attempt to make sense of how a seamless tube could arise from undifferentiated matter.

Galen himself gives clues to this logic. He insists elsewhere that Nature constructs parts at the earliest stage of generation using her four faculties (warming, cooling, drying, moistening) and that these faculties act upon the substrate by altering its mixture.⁽³⁾ When he says that vessels are formed by “breathing through” the substance, he does not imply that a literal cosmic craftsman leans over the embryo and blows. Instead, he maps the invisible formative tension (tonos) onto a craft process that makes it intelligible. The mixing and blowing are not poetic fantasies but explanatory devices anchored in the behavior of the four qualities.

The same semi-literal logic appears in On the Formation of the Embryo, where Galen assumes that the earliest vessels arise when the seminal and sanguineous matter thickens into a viscid substrate capable of being stretched into hollow forms.⁽⁴⁾ In Mixtures he explains this as a process in which tension produces the vessels, just as solidification produces bone or hoof.⁽⁵⁾ Vessels are thus the tense outcome of the right blend of qualities, just as bone is the solid outcome.

What emerges is not a contradiction between metaphor and mechanism but a convergence. Galen’s embryological metaphors are the closest thing he can offer to an intelligible causal model for processes hidden from view. They function as analogical mechanisms: models that behave like the phenomena they explain. When he likens vessel formation to blowing wax, he is not imagining a divine craftsman literally at work but describing the logic by which Nature creates a hollow channel out of a plastic mass. The metaphor is a scaffold for demonstration, a speculative mechanism expressed in the language of craft.

The question “Did Galen believe this literally?” thus misfires. For Galen, the plasticity, the blowing, the mixture, the tension: all are literally real as causal powers even if their imagery is artisanal. His embryology shows how metaphor and mechanism fuse at the very moment life begins.

The Animated Body: Blood, Pneuma, and the Powers of Nature

To follow Galen’s thought, one must also follow his language, for his metaphors are not sequential but cumulative. What begins as architecture becomes organism; what begins as structure becomes movement. This cumulative logic becomes clearest when one traces how his metaphors unfold alongside the actual movement of nourishment and blood through the body.

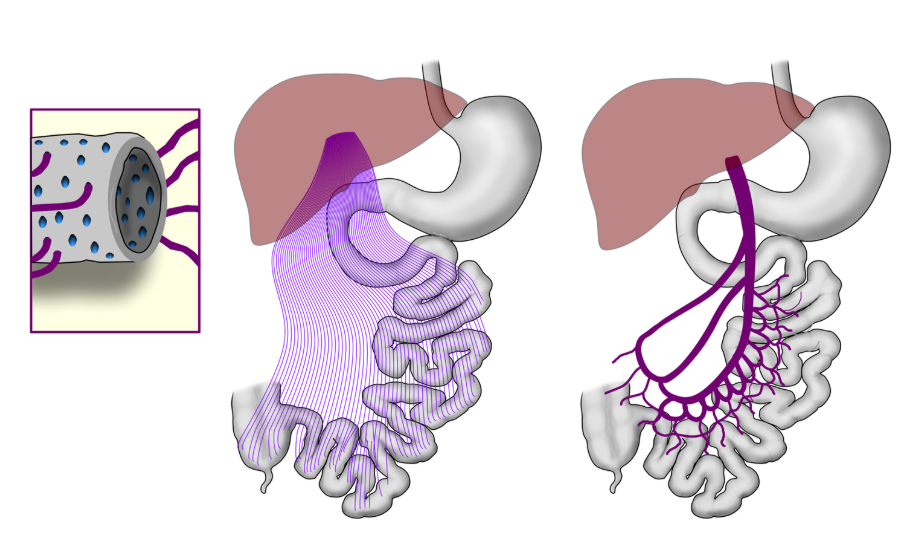

To understand how these metaphors take shape in the body, one must begin with the outline of his physiology, how nourishment, blood, and spirit move through the body. Food enters through the mouth, passes down the esophagus to the stomach, and is transformed there into chyle. The chyle travels through the mesenteric veins to the liver, where it is perfected into blood. From the convex surface of the liver, this newly formed blood enters the great vein, the single venous trunk that divides into one major branch upward toward the head and upper body, a small offshoot toward the heart, and another major branch downward to the lower body. As these venous branches subdivide, the blood they carry is gradually taken up by the surrounding tissues, for in Galen’s view the veins are not conduits of return but open-ended distributive channels whose contents dissipate at their terminals.

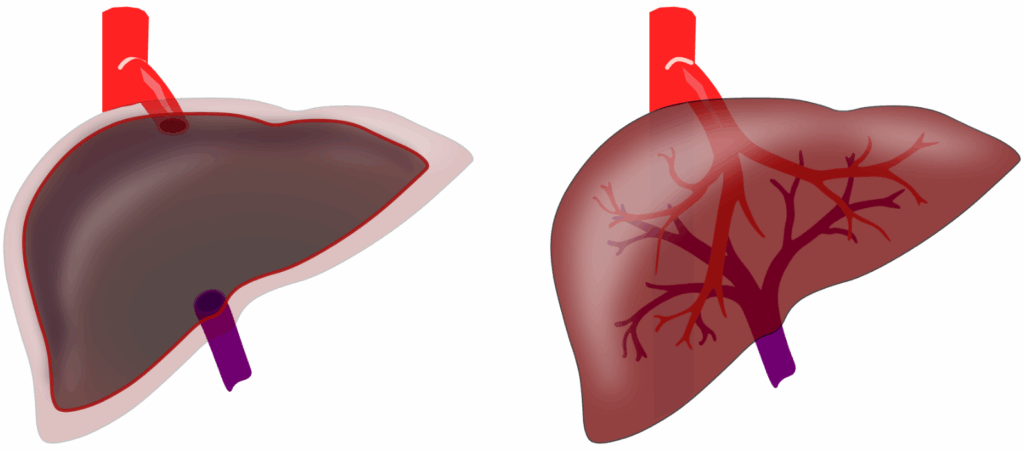

The heart, for Galen, is the “principal viscus,” a cone-shaped organ set almost in the middle of the thorax so that it is well protected and evenly cooled by the surrounding lung,10 yet remains the hottest part of the animal, a hearthstone that “must always be on the boil.” Around its base runs a crown of vessels: a coronary vein that nourishes its hard flesh and a coronary artery that cools that nourishing vein to preserve the heart’s innate heat.

Within this organ a portion of the venous blood passes through the tiny pores of the interventricular septum into the left ventricle, where it mixes with the pneuma drawn from the lungs via the vessels we would call the pulmonary artery and vein, though Galen classified them by wall thickness and pulsation.11 In this chamber the blood is enlivened and refined, acquiring the vital spirit that enables motion and sensation. From here it enters the great artery, the aorta, which rises from the heart like a living trunk before dividing into branches that reach the head, limbs, and trunk. As these arterial branches become progressively finer, their contents too are taken up by the surrounding tissues. Like the veins, the arteries form an open-ended system, distributing their mixture of blood and pneuma outward until it vanishes into the parts that require it.

The venous and arterial trees mirror one another in form: each arises from a single source, branches in orderly fashion, and spends itself in service of the parts. But their functional unity does not lie in this symmetry. The arteries possess their own distinctive power—a pulsative faculty that runs from the heart along their coats and allows the entire arterial tree to dilate and contract with its source. This rhythm concerns arteries alone. What truly binds the two systems, Galen insists, are the innumerable “common openings” where arteries and veins meet. Through these tiny junctions the arteries draw from the veins during diastole and return a trace of pneuma in exchange. Morphology provides the parallel; inosculation provides the unity.

Throughout the body, this conceptual unity is secured by the close anatomical pairing of arteries and veins. Galen describes them as intricately interwoven, their junctions formed by “common openings” that, though invisible to the eye, allow the two systems to communicate in action. Through these tiny passages the arteries draw from the veins during diastole and return a trace of pneuma in exchange. No artery exists without a companion vein, though many veins run unaccompanied, for all parts require nourishment while not all require the same degree of innate heat.12 These inosculations also explain why wounding a major artery empties the veins as well: the two systems drain together because they share a continuous network of junctions. Nature’s design therefore joins the arterial and venous trees not only in form but in action, creating a community of vessels that nourish, warm, and enliven the body through mutual exchange. Galen extends this reciprocity to the heart and lung themselves, which he casts as partners in continual barter: the heart feeds the lung with elaborated blood, and the lung returns refined air in exchange.

Underlying this anatomy is a theory of life itself. The body’s motions are governed not by pressure or mechanics but by natural faculties that draw, retain, alter, and expel according to need, the powers that secure the proper balance of matter and form. Every part possesses its own faculty of attraction, by which it pulls toward itself what is useful and repels what is harmful; the tissues take up blood and pneuma not by force but by an innate desire for what sustains them. These faculties are expressions of the soul, which Galen, following the Platonic and Aristotelian tradition, divides into three kinds: the vegetative or nutritive soul shared by all living things, the vital soul seated in the heart and carried by the pneuma, and the rational soul unique to humans, whose command reflects the divine intellect. Blood, pneuma, and faculty thus form a single continuum of life, matter animated by spirit and directed by reason.

To read Galen today is to recover that unity of science and meaning. His body is not merely a machine but a moral and cosmic order, animated by purpose as much as by motion. He matters because he shows how the imagination of nature can be rational without being reductive, a reminder that the history of medicine is also the history of how we imagine life itself.

Nature the Architect: The Body as City

In describing the routes of food from mouth to stomach, Galen adopts the language of the polis.13The body is a city governed by Nature, who plans its thoroughfares with the prudence of an engineer. “It is not possible that any city should be better ordered than the body, which Nature has constructed for the common good of all its citizens.”³ The mouth is a gate, the esophagus an avenue, the stomach a storehouse, and the veins and arteries the streets and aqueducts that distribute supplies. Each part performs its civic duty in service to the common good, and the organism as a whole functions as a polis governed by reason.

This metaphor is more than poetic. It expresses the teleological principle that underlies On the Usefulness of the Parts: every structure exists for a purpose, and the order of that purpose reflects the harmony of Nature’s design. The alimentary routes that carry food from intake to storage foreshadow the body’s first vascular roads, the portal veins, which transport the partly refined nutriment toward the liver. Only after this stage do the major venous and arterial networks appear, conveying fully formed blood and pneuma throughout the body. The body, like the city, depends on organized movement through properly constructed channels.

Galen calls the stomach “a work of divine, not human, art”³ a phrase that elevates infrastructure from the practical to the theological. The smooth functioning of digestion becomes a hymn to the rational craftsmanship of Nature, who acts both as builder and steward. This civic order governs only the alimentary phase of life, the world of gates, storehouses, and delivery routes that convey food to the liver. Once the chyle enters the veins and is transformed into blood, roads no longer suffice as an image. What had moved as cargo now flows as current.

The Economy of Nutrition

The stomach performs the first pepsis, an artisanal transformation akin to milling or cleaning grain. Galen calls it a “great boiling cauldron surrounded by burning hearths,” contracting around its contents until they have been softened and altered by heat. Digestion is imagined as purification and improvement. Impurities are expelled downward as waste, while the purified portion is refined and carried onward to the liver, where Nature completes her work. Galen frames this not chemically but vocationally; the stomach has a faculty analogous to a skilled artisan’s craft.

Although the stomach prepares nutriment for the parts that follow, it works first for itself. It contracts around the food and draws off the portion most appropriate to its own coats, “enclosing it on all sides” until it is satisfied. Only then does the pylorus open and the remainder is expelled “like an alien burden” toward the intestines. The material is “alien” only from the stomach’s point of view, for what it cannot use becomes precisely what the liver requires for its own craft of elaboration. In this early stage of pepsis, the stomach behaves less like a servant passing material forward and more like a craftsman who keeps the best of what he has made; the rest continues its journey only after the organ has taken its own due.

The veins of the portal system then appear as city porters, carrying the processed nutriment from the stomach to the liver, the city’s public bakery, where it is baked into true blood. The prevailing direction of flow becomes visible: nutriment moves inward toward the liver to be perfected into blood, and from there outward through the veins to nourish the body. The veins supply nourishment; the arteries convey vitality, carrying refined pneuma from the heart and lungs to every part.

This imagery also conveys a theological economy. The body is a polis animated by purposeful labor, each organ performing its appointed task under Nature’s supervision. The stomach, veins, and liver together transform nourishment into life. Galen’s urban physiology anticipates a systems view of the body as an organized whole sustained by cooperation among its parts, though his logic remains teleological rather than quantitative, moral rather than mechanical.

The Hierarchy of Service

When Galen writes that “the liver has received the nutriment already prepared by its servants,” he reveals the hierarchical structure of his physiology.14 Nature’s household is a divine economy in which each organ performs its appointed task.15 The chain of service runs from mouth and esophagus (intake and routing) to stomach (first concoction), to veins (transport and preliminary preparation), and finally to the liver (second concoction and elaboration into blood). The lower organs serve the higher, yet all cooperate toward a single end. Galen describes this as a continuous series of preparations in which “each [part] prepares and predigests the nutriment for the part that comes after it in the continuity of distribution.” The chain from mouth to stomach, from stomach to veins, from veins to liver, and from liver to the rest of the body is thus not a loose association of functions but an ordered procession of crafts, each passing on a more refined material to the next.

The Greek pepsis means “cooking” or “ripening,” a transformation by heat that begins in the stomach and reaches completion in the liver, making matter resemble the living body. The liver’s work of elaboration is the final perfection, the finishing touch that differentiates crude nutriment into true blood. The theological meaning is clear: every organ fulfills its purpose in obedient sequence, mirroring the cosmic hierarchy. Nature’s workshop is also Nature’s temple, where utility is a form of piety.

The Fermentation of Life

As the chyle enters the portal veins on its way to the liver, Galen introduces one of his most vivid images: this mixture is like new wine still working in its casks. Nature’s alchemy converts the crude into the vital, the inert into the animate.16In this fermenting mass, the heaviest residues gravitate downward to become black bile, gradually settling toward the spleen, whose loose, sponge-like flesh is designed to attract and work over this thick, earthy sediment.17 The lightest, most fire-like portion rises upward as yellow bile, destined for the intestines and gall bladder. Between these extremes lies the middle, fermenting must from which the liver fashions true blood.

For Galen, this fermentative stratification is not metaphor but mechanism. Heat ripens the mixture toward perfection: the coarse and earthy is pressed downward as dregs; the sharp and fiery ascends as choler; and the balanced, temperate portion is seized by the liver for elaboration into blood. In this economy of residues, each organ takes what is “appropriate” to its nature. The spleen draws down the atrabilious lees and alters what it can use as its own nutriment; the stomach and intestines receive the overflow of yellow bile; and the liver holds the finest part long enough for Nature to complete the second pepsis that makes nutriment resemble the living body.

Fermentation here expresses both a physical and a moral order. What is pure rises, what is coarse sinks, and the middle substance—the part of just proportion—is transformed into blood. The liver’s work is thus the culmination of a stratified process in which heat separates, distributes, and perfects the mixture so that each organ receives its due and the body as a whole is nourished.

The Metamorphosis of Flow

Once blood has been fashioned in the liver, Galen changes his way of seeing, not by abandoning earlier images but by adding new ones that reveal different aspects of the same system. The nutritive landscape that had been terrestrial, rooted in soil and animated by the measured labors of artisans and porters, begins also to appear as a flow of living current. The veins that had drawn sustenance upward like roots from the intestinal earth now carry blood as water through a branching network of channels. The liver becomes a reservoir, and the vena cava, the great trunk, conducts its streams outward in every direction. The body’s order of nourishment therefore undergoes not a replacement of metaphors but an enrichment of them, a shift in element rather than in form.

Form remains botanical even as content becomes hydraulic. The veins branch as trees yet act as conduits of water. Galen himself calls the vena cava “a sort of aqueduct full of blood,” with “very many conduits, both large and small, leading off from it” into every region, and likens it to the stem of a tree whose double trunk ascends and descends to supply the upper and lower body. Nature’s design, constant in geometry, moves between registers of earth and water, root and river, each metaphor capturing what the other cannot. What had risen as sap now courses as stream. What had moved as cargo now flows as current. Roman readers would have recognized in this dual imagery both the natural and the engineered, the living tree and the civic aqueduct, each an emblem of life carried from source to destination. The veins therefore inherit the virtues of both. They are the organic roots of the body and the public works of Nature, distributing the vital fluid that sustains its commonwealth of flesh.

This hydrological imagination also carries theological meaning. The aqueduct is not merely an architectural metaphor but an expression of Providence. Blood, like water, must reach every quarter, neither stagnating nor flooding. Through the aqueducts of the veins, the body becomes a self-regulating city whose measured distribution expresses the care and foresight that Nature exercises in all her works. In this sense every organ is a kind of stomach in miniature. Each draws the nutriment that lies alongside it, keeps what is useful until it is “thoroughly satisfied,” then makes that material adhere and finally assimilates it to its own substance, expelling the excess. The local faculty repeats, on a smaller scale, what the gastric faculty does on a larger one.

The Dynamic Metaphor: Nature’s Faculties in Motion

In On the Natural Faculties, Galen turns from the architecture of channels to the inward powers that govern living parts, and these he describes in organic rather than hydraulic terms. Nature is no longer the architect who builds but the artisan who acts. Each part functions according to its distinctive mixture of the four elemental qualities, and the faculties express this mixture in motion. Her instruments are the four faculties—attractive, alterative, expulsive, and formative—through which she performs her unceasing work. The veins do not merely contain; they draw, as roots draw sap from the earth.

Galen distinguishes two modes of attraction that make this invisible labor intelligible. Some parts draw by the simple tendency of an emptied space to be refilled: when a cavity such as the ventricle, artery, or stomach dilates, it behaves like a craftsman’s bellows or a hollow tube plunged into water, creating a space into which the nearest, lightest material must rush. He explicitly rejects the image of arteries as passive wineskins that swell when pushed from behind, insisting instead that they are filled because they actively expand. Other parts attract by “appropriateness of quality,” a lodestone-like affinity—Galen’s preferred image for the selective attraction of like to like—by which a vein, organ, or tissue draws what is akin to it out of a mixed mass. The first mode is mechanical and indifferent; the second is selective, capable of pulling off the finer from the coarser through minute openings. By pairing vacuum with magnet, Galen endows the vascular tree with both motion without pressure and a kind of discriminating desire.

Galen applies the same analogy more broadly in his account of nutrition. Some parts draw by the simple mechanics of an expanding cavity, but others draw by appropriateness of quality, the selective attraction he illustrates with the Heraclean stone. The magnet becomes his emblem for this discriminating pull: from a mixed mass, each part draws only what is akin to it, just as the lodestone draws iron alone. This image helps him explain how tissues take up the fine nutritive portion of blood, leaving the coarser residues to continue their course toward organs designed to process them.

Once these modes of attraction are in place, movement follows not a closed loop of circulation but a pattern of dispersal. Blood moves as traffic does in an open city: always seeking the broadest, least-resistant routes, diverted or slowed by gates, constrictions, and the shifting pressures of neighboring parts. Flow is not dictated by a single engine but by the interplay of pathways and resistances.

Such movements form a sympathetic choreography. As Hippocrates put it, there is a “concordance” in the motions of air and fluid: each part acts upon what is near it and is acted upon in turn. Movement is not a single push or pull but a shifting network of attractions whose balance changes with heat, need, exertion, or age. Because these forces (vacuum, lodestone-like affinity, peristalsis, heat, compression) are local and variable, flow is not unilinear. The same pathway may draw inward at one moment and expel outward at another. Bidirectionality is not an anomaly but an expectation in Galen’s system.18

Galen extends this image down to the periphery. The vena cava is “a sort of aqueduct full of blood,” feeding countless conduits that irrigate the limbs and viscera, while the tiny intervals between fibers and membranes act as little caverns where the juice of the blood is presented, made to adhere, and finally assimilated. Nourishment appears as a dew-like moisture that settles over the parts, each organ drawing what is useful, transforming it into its own substance, and passing on the surplus as excrement for the next in line. Each part attracts what is proper to itself and rejects what is alien, like citizens discerning the common good.

Nature distributes the pabulum in every direction, her vessels like roads intersecting the entire body. The lung participates in this artisanal economy as well: just as the liver concocts nutriment into blood, the soft, loose-textured flesh of the lung concocts outer air into pneuma, refining it stepwise before the heart perfects it. She has contrived exits for waste lest the workshop be fouled, and she tends the vital heat of the heart as one tends a hearth, the lungs fanning its flame so that it burns steadily without consuming its source. “Nature has harmonized the faculties,” Galen writes, “as the musician tunes his strings.” The body becomes not merely an edifice but an organism of purpose and will, a workshop of living reason in which each part acts, desires, and cooperates in the music of life.

The same faculties that secure nutrition also govern excretion, for Nature’s household operates by constant balances of intake and discharge. What cannot be assimilated moves on as superfluity: yellow bile to the intestines, black bile to the spleen and stomach, the thin, whey-like serum to the kidneys, and the finest residues outward through skin and breath as visible sweat or insensible vapor. In this scheme the skin itself functions as a porous lung: when the terminal arteries dilate, they draw in air through fine openings at the surface to cool and fan the body’s heat; when they contract, they expel smoky residues so that, as Galen likes to echo Hippocrates, “the whole body breathes in and out.” Even hair becomes a miniature botany of excretion, its buried portion likened to the root of a blade of grass wedged in the pore, and its visible shaft to the plant that breaks through the surface under the pressure of thickened, sooty vapor.

Galen even pauses to consider whether the kidneys might act as simple sieves, like wicker strainers separating curds from whey, only to reject that model in favor of attraction: the kidneys do not filter the whole stream but draw the serous excrement toward themselves from the vena cava because it is the fluid “most appropriate” to their nature. As elsewhere in his physiology, he tests a mechanical possibility only to reaffirm that Nature works by selective affinity, not passive filtration.

The Arboreal Metaphor: The Tree of Life

The arboreal image that has threaded through Galen’s physiology becomes fully explicit when he describes the entire vascular system as a living plant. He is especially concerned with origin. The liver is the source of the veins: the portal vein rises from its concavity like a trunk, its branches running outward through the liver and then downward through the mesentery as roots that sink into the intestinal soil. From its convex surface, the vena cava emerges as a single massive trunk that divides toward the upper and lower body.

The heart, by contrast, is the source of the arteries. The aorta springs from the left ventricle like a tree from the earth, divides into two great limbs, and then into progressively finer branches, twigs, and terminal shoots that reach every part. Even the pulmonary artery, which descends to the lungs, can be imagined as a buried root that drinks air as nourishment for the heart’s flame. In this vision, nourishment, respiration, and motion belong to one continuous structure of growth.

The tree metaphor fuses morphology with teleology. As roots draw moisture toward the trunk, so the veins draw nutriment toward the liver. As branches reach toward the light, so the arteries convey vitality to the periphery. The image unites form and purpose, revealing that Nature’s architecture and Nature’s action express the same rational order.

The Heart’s Attraction: Flame, Bellows, Magnet

For Galen, the heart is not a pump but a living fire that draws life to itself. It is not, in his terms, an ordinary muscle but a special hard flesh woven from longitudinal, transverse, and oblique fibers, whose involuntary and ceaseless motion sets it apart from the voluntary muscles that move only at the animal’s command.

Dilation is not passive but active: the widening ventricle behaves like a bellows that draws in air or like a long tube lowered into water from which the air has been sucked. The newly created vacancy pulls the nearest, lightest material toward itself. This artisanal logic of suction explains why Galen treats diastole as the heart’s primary act—an expansive inhalation that snatches and drinks up blood and air through its chambers. Galen parses this motion into a choreography of fibers: the longitudinal fibers widen the cavity in diastole, the transverse fibers constrict it in systole, and the oblique fibers tense in the brief pause between them to clasp the contents, allowing the heart to “enjoy what has been attracted” before it is expelled. In On Anatomical Procedures, he describes what the eye itself can witness: expose the heart in a living animal and you see it striking the chest wall, expanding and contracting as though breathing.¹²

If attraction explains why the heart draws, rhythm explains how it moves. Galen casts the heart as a living furnace whose alternating expansions and contractions mimic the breaths of a forge. Having widened to draw in blood and air, it then contracts to expel what has been altered by heat. The arteries answer this rhythm like paired bellows, expanding in sympathy with the heart’s living fire. He makes the pulse a second form of breathing: just as respiration preserves the innate heat of the heart, so the rhythmic expansion and contraction of the arteries preserves the warmth diffused through the parts, doing for the body what breathing does for the heart alone.

The auricles stand at the threshold of this motion as both buffers and reservoirs. Galen imagines that when the heart exerts its full powers of attraction it would tear the thin-walled vena cava and pulmonary vein to pieces were they not protected by these sinewy outgrowths, which tense and contract as the ventricles dilate. The auricles absorb the violence of the suction and at the same time compress their contents forward, easing the transfer of blood and air into the chambers. He adds that the vena cava itself requires further safeguarding, for it is continually shaken by the motions of the heart, lung, diaphragm, and thorax; Nature therefore buttressed it with soft supports such as the thymus and the so-called fifth lobe of the right lung so that this single-tunicked vein would not rupture beside so violent an organ.

But mechanical suction alone cannot explain the heart’s power to draw. o clarify this deeper dimension of attraction, Galen reaches for a familiar analogy: the Heraclean stone, his standard example of the attractive faculty (dynamis helktikē). He does not liken the heart itself to a magnet, but he uses the lodestone to illuminate a general principle — that living parts attract what is appropriate to them not by force or pressure but by a natural affinity. In the heart, this faculty accompanies diastole: just as the lodestone draws only iron, not straw, so the heart draws the substance suited to its nature. The analogy does not define the heart’s substance; it clarifies its mode of action, a selective pull grounded in the vital heat that animates all its movements.

He compares this motion to a smith’s bellows that draws breath as it widens, to a lamp flame that lifts oil upward by its heat, and to the Heraclean stone that attracts iron by natural sympathy. Each image unfolds a different register of vitality—mechanical, elemental, and magnetic. Together they reveal the heart as the central agent of attraction, the source of innate heat and motion. Around this magnet of life the auricles propel and the vessels conduct, all responding to the heart’s expanding pull.

At each mouth of the heart Galen places membranous valves whose usefulness is purely mechanical yet fully teleological. They grow, he says, to prevent reflux, so that the heart may not “labor in vain” by sending matter back toward parts that should instead be supplying it. In this arrangement, the cone of hard flesh, the triple weave of fibers, the shock-absorbing auricles, and the one-way valves together form a furnace of innate heat whose every motion, however mechanical, is ordered to the preservation of life.

Thought Experiments of Design

Alongside the metaphors that animate his physiology, Galen also reasons through a series of counterfactual anatomical models. These thought experiments reveal a different dimension of his method. Instead of imagining the body as a city, tree, or aqueduct, he imagines how Nature might have constructed it differently, and why she chose the structure that exists. These counterfactuals are not metaphors but demonstrations of purpose, exercises that expose the teleological rationality behind the body’s architecture.

One of Galen’s most striking demonstrations concerns the structure of the portal vein. He asks why Nature did not fashion thousands of tiny vessels rising from every part of the intestine, each carrying nutriment separately to the liver. Such a design is anatomically possible, Galen insists, yet Nature rejected it. A forest of thin vessels would be exposed, fragile, and easily injured. Their sheer multitude would create confusion rather than order. Instead, Nature selected the wiser plan: a single robust venous trunk, deeply situated and well protected, that gathers nutriment from the intestinal region and conveys it securely to the liver. This, for Galen, is proof that Nature chooses not merely what can exist, but what should exist.

Galen develops a second counterfactual model concerning the structure of the liver itself. Why, he wonders, is the liver not a hollow cavity, with the portal vein entering and the hepatic vein leaving like pipes in a vat? He rejects the idea because blood cannot be formed in a void. What the liver requires, he insists, is not an empty vat but a dense mesh of interlacing portal and hepatic branches that slow the flow, multiply contact with the parenchyma, and give Nature time to “change the nutriment completely into blood.” For elaboration to occur, nutriment must be slowed, retained, and spread across a dense network of communicating vessels. Interlacing channels create surface area; they hold the blood long enough for transformation. A cavity would let nutriment pass too swiftly, defeating Nature’s purpose. The meshwork of vessels, therefore, is a functional necessity.

From Galen to Harvey

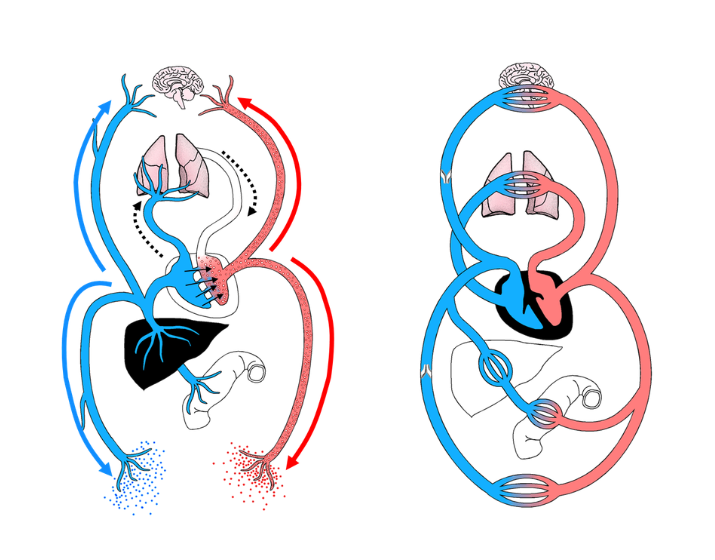

In Harvey’s world the heart becomes a machine. Motion replaces attraction; circulation replaces desire. What Galen had taken to be the heart’s violent diastole, the outward strike of a furnace drawing in its fuel, Harvey redefined as systole, the contraction of a pump driving blood forward under pressure. The body is no longer a moral city but a hydraulic system driven by pressure. What Galen saw as purpose Harvey measured as pulse.

Yet something is lost in this transformation. The world that Galen pictured as an order of living waters becomes a hydraulic circuit. Galen’s veins and arteries are alive; they draw, select, and respond to need. Harvey’s are largely inert; they conduct. In gaining precision, physiology forfeits a certain intimacy. Galen’s uneasy compromise over arterial blood—his attempt to hold together one matter, two mixtures, and a double system of channels—marks the limit of a physiology that must honor both what the knife reveals and what his teleology demands. Harvey’s circulation solves the mechanical problem at the cost of dissolving that tension.

To see Galen through Harvey is to recognize how drastically the language of life has shifted—from attraction to propulsion, from faculties to forces, from civic labor to mechanical work. To see Harvey through Galen is to recall that our own models rest on images as surely as his did, and that every new mechanism brings with it a new metaphor.

Right (Harvey): Harvey’s circulation (red = arterial, blue = venous) forms a closed loop. Blood moves from the right heart to the lungs, then from the left heart through the arteries, returning through the veins to the heart in a continuous, unidirectional circuit. The arterial and venous systems are connected by capillaries rather than open ends, and blood is recirculated, not consumed. This side-by-side contrast highlights the key differences: Galen’s dispersive, open-ended vascular trees with outward flow from two sources, versus Harvey’s closed, circular system driven by the heart as a pump.

Conclusion

Galen’s metaphors are not stylistic embellishments but instruments of reasoning. Each image reveals a different dimension of the same living order. Veins can be roots that draw and rivers that distribute, because growth and flow belong to one design. Cities, workshops, households, trees, and currents are not competing models but complementary analogies that converge on a single teleological vision. Nature builds, transforms, separates, moves, and harmonizes with purpose, and Galen gives each of these acts its own metaphor. The result is a physiology that thinks in images, a conceptual architecture in which language becomes a mode of understanding.

To follow Galen’s metaphors is to see how the imagination of nature can itself be a form of knowledge. To read him now is not to return to a discarded physiology, but to rediscover how deeply our own medicine still thinks in images, and how much of our science continues to depend on the ways we picture life.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Vivian Nutton for his invaluable conversations and guidance over many years, and to Steve Moskowitz, whose artwork has illuminated the structures and metaphors explored in this essay.

Note on Sources

This essay draws primarily upon my own readings of Galen’s surviving works, especially On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body (UP), On the Natural Faculties (NF), On the Pulse for Beginners (PB), On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato (HP), and On Anatomical Procedures (AP). I have relied on modern English translations and have developed the interpretations here through close study of Galen’s language, imagery, and argumentative structure. I have also benefited from important modern scholarship, which has informed certain historical and philological contexts without determining the readings offered here.