Case

An 80-year-old man, previously well, was diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia. He eats meat and has no evidence of malabsorption. Both upper and lower endoscopy were negative, and he is not on anticoagulants and reports no bleeding symptoms. The clinical question is whether video capsule endoscopy has a role in further evaluation of his unexplained iron deficiency anemia.

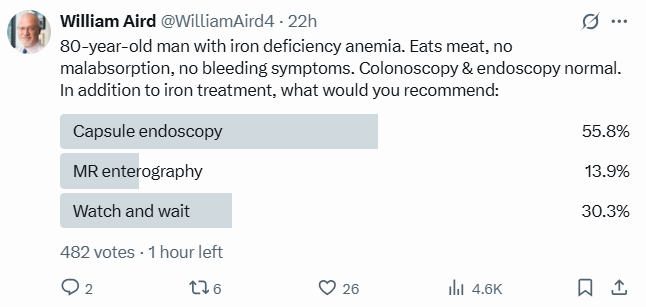

Twitter Poll

For AI-Generated Podcast Addressing This Case

Expert Opinion

- UpToDate:

- Recommendation:

- VCE may be used to evaluate suspected small bowel bleeding in adults, to evaluate patients with suspected Crohn disease, assess mucosal healing, and to detect small bowel tumors. In addition, VCE is being used to detect small bowel injury associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Notes:

- The most common indication for VCE is the evaluation of suspected small bowel bleeding (including iron deficiency anemia).

- The overall yield of VCE for suspected small bowel bleeding has been reported to be in the range of 30 to 70 percent.

- A large meta-analysis included 227 studies with 22,840 procedures, 66 percent of which were done for suspected small bowel bleeding. In that analysis, the detection rate for VCE in patients with suspected small bowel bleeding was 61 percent.

- A large meta-analysis included 12 studies with a total of 1703 IDA patients. The diagnostic yield of VCE for overall lesions in the small bowel was 61%. When analyzing only small bowel lesions likely responsible of IDA, the diagnostic yield was 40%

- In a study of 911 patients with suspected small bowel bleeding published subsequent to the meta-analysis, 509 patients (56 percent) had a lesion identified on capsule endoscopy that was thought to be responsible for the bleeding [75]. The findings included:

- Small bowel angiodysplasia – 22 percent

- Small bowel ulcerations – 10 percent

- Small bowel tumors – 7 percent (benign and malignant)

- Small bowel varices – 3 percent

- Blood in the small bowel with no lesion identified – 8 percent

- Esophagogastric lesions (eg, esophagitis, gastritis) – 11 percent

- Colonic angiodysplasia – 2 percent

- A meta-analysis of 14 observational studies compared capsule endoscopy with other tests for suspected small bowel bleeding. They estimated that the overall yield (i.e., the yield of VCE for any small bowel findings) of VCE (63 percent) was significantly higher than for push enteroscopy (26 percent) and barium studies (8 percent).

- The yield appears to be higher for patients who take antithrombotic agents who are undergoing small bowel VCE for suspected bleeding compared with patients who are not taking antithrombotics.

- The diagnostic yield of VCE (ie, the percentage of studies that provided a clear-cut explanation for the bleeding) is highest when it is performed as close as possible to the bleeding episode and in patients with overt (visible), rather than occult, bleeding.

- Recommendation:

- The Cost-Effectiveness of Video Capsule Endoscopy (PMID: 33743935):

- Small intestinal bleeding (occult or obscure) is defined as GIB from an unidentified source that recurs despite negative endoscopic examinations.

- Based on previous literature, VCE used in this scenario can increase the diagnostic yield by 25% to 50% compared with push enteroscopy or angiography.

- Cost utilization analyses have demonstrated that when definitive therapy is needed, push enteroscopy is the most cost-effective strategy, whereas when localization and visual diagnosis are needed, VCE is the most cost-effective.

- In a robust international study, Mueller and colleagues34 performed a predicted cost model incorporating sensitivities and specificities of 7 controlled trials from 5 countries comparing initial VCE versus push enteroscopy. In all 5 countries, VCE was more effective and less costly than push enteroscopy when prevalence of disease was at least 30%. The most common use of VCE was at a prevalence of 50%. The findings support the use of VCE for obscure GIB, when localization of the bleeding source is needed.

Clinical Practice Guidelines

- British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia in adults (PMID 34497146)

- Recommendations:

- In those with negative bidirectional endoscopy of acceptable quality and either an inadequate response to IRT or recurrent IDA, we recommend further investigation of the small bowel and renal tract to exclude other causes (evidence quality—moderate, consensus—85%, statement strength—strong).

- We recommend capsule endoscopy as the preferred test for examining the small bowel in IDA because it is highly sensitive for mucosal lesions. CT/MR enterography may be considered in those not suitable, and these are complementary investigations in the assessment of inflammatory and neoplastic disease of the small bowel (evidence quality—high, consensus—100%, statement strength—strong).

- Notes:

- CE is now the first-line test for assessment of the small bowel in the setting of covert bleeding/IDA, as it has a higher diagnostic yield than radiology.

- A pooled diagnostic yield of 66.6% (95% CI 61% to 72%) has been reported in a systematic review of CE in IDA.

- Angioectasia, Crohn’s disease and NSAID enteropathy are common findings.

- Factors such as transfusion dependence, increasing age and comorbidity all positively influence the diagnostic yield.

- The pathology found on CE is actually within reach of standard gastroscopy in up to 28% of cases.

- While the pick-up rate for small bowel pathology is significantly higher in the elderly, there is emerging evidence of the value of CE in younger age groups with IDA.

- The rebleeding potential is low following a negative CE, and a conservative approach can in general be followed.

- CE does however have a miss rate, importantly for small bowel tumours.

- Indications warranting additional investigation after a negative CE may include a further Hb drop of >40 g/L, and a change in presentation from occult to overt bleeding.

- In the context of suspected small bowel bleeding including IDA, there is limited evidence to support repeating CE after an initial negative study in cases where there remains a strong suspicion of undiagnosed pathology, with a yield of up to 45%.

- The majority of small bowel lesions underlying IDA are subtle vascular or inflammatory abnormalities, undetectable by conventional radiology.

- Recommendations:

- AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Gastrointestinal Evaluation of Iron Deficiency Anemia (PMID 32810434)

- Recommendation:

- In uncomplicated asymptomatic patients with iron deficiency anemia and negative bidirectional endoscopy, the AGA suggests a trial of initial iron supplementation over the routine use of video capsule endoscopy. Strength of recommendation: Conditional; Quality of evidence: Very low1

- Notes:

- No studies that directly compared small bowel investigation of any type with iron replacement therapy or clinical observation were identified, and no direct evidence that performing video capsule endoscopy reduces the risk of adverse outcomes was found.

- The Technical Review Panel considered studies of the diagnostic yield of small bowel evaluation in the absence of overt gastrointestinal bleeding in formulating this recommendation.

- In the technical review, pooled analysis of 16 studies of the diagnostic yield of video capsule endoscopy found that small bowel malignancy was identified in 1.3% (95% CI, 0.8%–1.8%).

- However, these studies were believed to be at very serious risk of bias due to the potential for referral bias and the inclusion of symptomatic patients.

- The diagnostic yield for malignancy in asymptomatic patients without overt gastrointestinal bleeding could not be determined from available evidence, and the diagnostic yield for other outcomes, such as inflammatory bowel disease, small bowel ulcers or erosions, and vascular lesions is also unknown.

- Available studies did not include an appropriate gold standard to define the sensitivity and specificity of video capsule endoscopy.

- Whether video capsule endoscopy leads to any change in clinical management in a clinically meaningful proportion of patients is unclear.

- Therefore, the evidence required to evaluate the benefits of video capsule endoscopy in IDA is not currently available.

- Given the uncertainty about diagnostic yield and effect on overall clinical management in asymptomatic patients without overt gastrointestinal bleeding, as well as concerns about resource utilization, the routine use of video capsule endoscopy is not well supported.

- A trial of adequate iron supplementation with further small bowel investigation only if iron deficiency persists may provide similar clinical outcomes, although no direct comparisons are available.

- Evidence on the utility of other methods of small bowel investigation, including computed tomography or magnetic resonance enterography, small bowel follow through, tagged red blood cell scintigraphy, push or deep enteroscopy, and angiography was also lacking.

- This recommendation does not apply to patients who have symptoms suggestive of small bowel disease or at higher risk of small bowel pathology, such as patients with increased propensity for small bowel angioectasias, in whom diagnostic video capsule endoscopy might otherwise be indicated.

- Similarly, video capsule endoscopy may be indicated in select circumstances where identification of small bowel pathology may alter medical management. Examples include patients who use anticoagulation or antiplatelet medications, in whom identification of a bleeding lesion may be important for prognostic or management purposes.

- Likewise, patients with anemia refractory to adequate iron supplementation may be appropriate candidates for video capsule endoscopy.

- Recommendation:

“A large evidence gap is apparent regarding the outcomes and proper techniques of small bowel investigation in patients with negative bidirectional endoscopy. Well-designed studies of the diagnostic yield of video capsule endoscopy and comparative studies of outcomes of initial iron replacement vs small bowel investigation would guide future practice. In addition, there is little evidence about the role of fecal occult blood testing and the comparative efficacy of various methods of small bowel investigation, such as video capsule endoscopy, deep enteroscopy, or magnetic resonance/computed tomography enterography, in this clinical scenario. Future studies that define patient subgroups that are likely to benefit from small bowel investigation are clearly needed. Finally, further research on the utility of repeating the diagnostic evaluation in patients with persistent or recurrent IDA and negative prior evaluation is needed.”

- European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline (PMID: 36423618)

- Recommendations:

- ESGE recommends small-bowel capsule endoscopy as the first-line examination, before consideration of other endoscopic and radiological diagnostic tests, for suspected small-bowel bleeding, given the excellent safety profile of capsule endoscopy, its patient tolerability, and its potential to visualize the entire small-bowel mucosa. Strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence.

- ESGE recommends small-bowel capsule endoscopy in patients with overt suspected small-bowel bleeding as soon as possible after the bleeding episode, ideally within 48 hours, to maximize the diagnostic and subsequent therapeutic yield. Strong recommendation, high quality evidence.

- ESGE does not recommend routine second-look endoscopy prior to small-bowel capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected small-bowel bleeding or iron-deficiency anemia. Strong recommendation, low quality evidence.

- ESGE recommends the performance of small-bowel capsule endoscopy as a first-line examination in patients with iron-deficiency anemia when small bowel evaluation is indicated. Strong recommendation, high quality evidence.

- ESGE recommends that in patients with iron-deficiency anemia, the following are undertaken prior to small-bowel evaluation: acquisition of a complete medical history, esophagogastroduodenoscopy with duodenal and gastric biopsies, and ileocolonoscopy. Strong recommendation, low quality evidence.

- Notes:

- Small-bowel (SB) bleeding is defined as bleeding in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract between the ampulla of Vater and the ileocecal valve.

- SB bleeding is suspected when a patient presents with GI bleeding but has negative upper and lower endoscopy findings; it can present as overt or occult bleeding.

- The diagnostic yield of small-bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) in patients with suspected small-bowel bleeding (SSBB) ranges from 55% to 62%.

- Compared with alternative modalities, SBCE has been consistently shown in prospective studies to be significantly superior to push-enteroscopy, computed tomography enterography (CTE), CT angiography and standard angiography [10], and intraoperative enteroscopy, and to be as good as DAE in evaluating and finding the lesion(s) causing the bleeding in patients with SSBB.

- Careful patient selection may improvethe diagnostic yieldof SBCEinpatients with SSBB. Diagnostic yield is greatest if the interval between SBCEandthelastbleeding episodeisas short as possible.

- Other characteristics associated with an increased yield include a history of an overt bleed, use of antithrombotic agents, inpatient status, male sex, older age, and liver and renal comorbidities

- The evidence published since the previous ESGE guideline and the most recent practice guideline on IDA confirm that, before evaluation of the small-bowel, patients with IDA should undergo a thorough anamnestic evaluation and a multistep diagnostic–therapeutic workup that includes endoscopic evaluation of the upper and lower digestive tract.

- The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guideline for the management of IDA in adults recommends that, before the SB evaluation is planned, an empirical iron replacement trial (IRT), should be performed with appropriate dosage and duration. According to the BSG guideline, endoscopic SB examination should be performed only if the target values are not reached in the initial IRT or if anemia recurs at the end of treatment. However, no clinical trials have compared the clinically relevant outcomes (e. g., diagnostic yield and possible diagnostic delay) in patients referred for SB study according to the IRT outcome. This policy may lead to different results in different subgroups of patients. Therefore, the available evidence appears insufficient to recommend using the IRT as a decision-making tool in deciding to perform an SB study.

- Several studies pursued the aim of identifying such predictive factors for SB pathology; diagnostic yield has been shown to correlate with:

- Male sex

- Older age

- Low mean corpuscular volume (MCV)

- Low hemoglobin values

- High transfusion requirement

- Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the last 2 weeks before SBCE

- Antithrombotic therapy H

- In recent years, new evidence has also emerged concerning the possible role of fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), either guaiac or immunochemical, as a filter test to select IDA patients for SBCE. Nevertheless, there is still insufficient evidence to recommend FOBT in routine practice as a screening tool for deciding whether to perform SBCE in IDA patients. Larger studies may better clarify its usefulness and lead to future guidance changes.

- In recent years, it has also been shown that, although there are some differences in terms of both diagnostic yield and the spectrum of findings between young and elderly patients, age is not a discriminating factor when SB studies are performed in patients with IDA and negative bidirectional endoscopy.

- According to previous ESGE guidelines, large studies have confirmed that SBCE is the test of choice for evaluating the small intestine in patients with IDA, both because of its high diagnostic yield and favorable safety profile.

- There is conflicting and inconclusive evidence about the role of second-look endoscopy before SBCE in IDA patients. Therefore, repetition of upper and lower endoscopies should be decided on a case-by-case basis, considering the timing and quality of upper and lower endoscopy performed before SBCE.

- SB neoplasia and diverticula are mural-based lesions that can cause IDA but can be missed at SBCE, and for which CTE has been shown to have higher sensitivity.

- Recommendations:

Back to the case

Most major clinical practice guidelines, including those from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), advise against the routine use of VCE in asymptomatic individuals with uncomplicated IDA following negative upper and lower endoscopy. Instead, they recommend a period of observation with oral iron supplementation and monitoring for recurrence or persistence of anemia (the majority of patients with unexplained IDA respond to iron supplementation alone, and only a minority have clinically significant small bowel pathology that alters management). This strategy is based on evidence that routine VCE in such patients has a relatively low diagnostic yield for life-threatening or treatable lesions and rarely changes management (i.e., low diagnostic yield [40–61%] and low clinical impact [most lesions identified are vascular or inflammatory and may not require intervention, especially in the absence of ongoing bleeding or symptoms]).2 The AGA notes that available studies are at high risk of bias, lack appropriate gold standards, and do not demonstrate that video capsule endoscopy improves patient outcomes or alters management in a meaningful way. Additionally, the prevalence of clinically significant small bowel pathology in this population is low, and resource utilization is a concern.

When to Consider Capsule Endoscopy:

- VCE may be considered if:

In summary, for this patient profile, current guidelines do not support immediate video capsule endoscopy. Ongoing reassessment—with iron trial and monitoring—is the appropriate next step, reserving VCE for cases of refractory anemia or if new symptoms develop.

Practical Summary:

- Trial of oral iron first: If anemia corrects and remains stable → defer VCE (most patients).

- Persistent/recurrent anemia or poor response → proceed to small bowel evaluation (VCE, enterography, etc.).