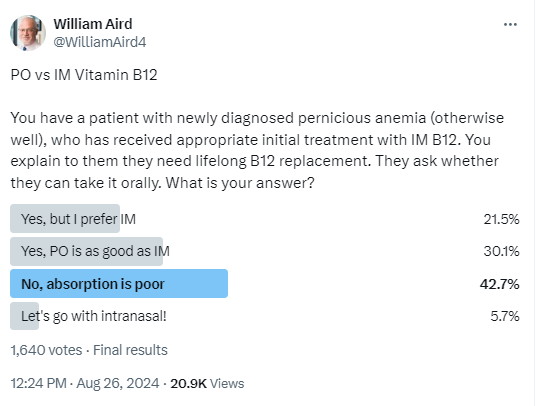

I posted a poll on Twitter that asked learners/users you would replace vitamin B12 in a patient with pernicious anemia, focusing on the choice between intramuscular (IM) and oral (PO) routes. Interestingly, the most popular answer was to treat with IM, not oral vitamin B12. In this tutorial, we will drill down on the question of IM vs. PO vitamin B12.

Introduction

- Traditionally, vitamin B12 replacement is administered intramuscularly (IM). However, oral vitamin B12 can be absorbed passively independent of intrinsic factor. Passive diffusion accounts for about 1% of total absorption, and this route of absorption is unaffected in patients with pernicious anemia. High doses of oral vitamin B12 (e.g. 1000 µg daily) may be able to produce adequate absorption of vitamin B12 even in the presence of intrinsic factor deficiency, and therefore may be an alternative to the intramuscular route for many people.

Bottom line

- Existing evidence comparing oral with IM vitamin B12 is suboptimal.

- A total of three randomized clinical trials have been published.

- Each of these studies shows that oral vitamin B12 is just as effective as IM B12 in terms of increasing serum vitamin B12 levels. However, none of the studies reported on hematological or clinical outcomes.

- There are differences in practice between countries, with Canada and Sweden favoring use of oral vitamin B12.

- The choice between PO and IM vitamin B12 seems ideal for shared decision making.

Nomenclature

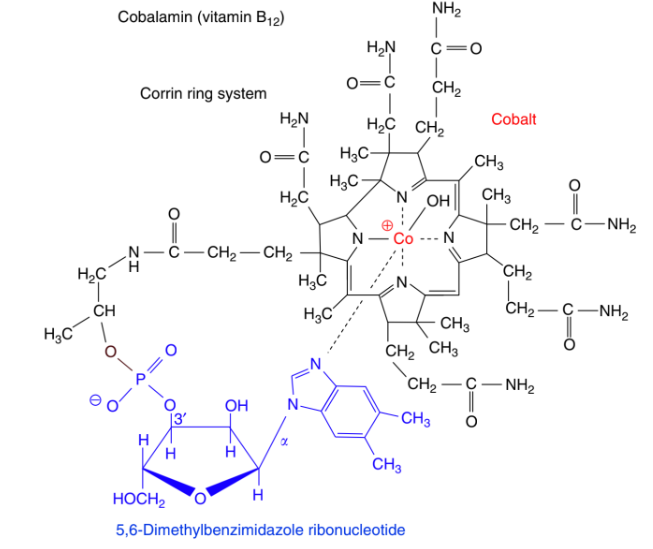

- Vitamin B12, one of eight B vitamins, is also known as cobalamin.1

- It consists of cobalt as the central atom and a corrin ring that encloses the metal atom.2

- In comparison with other B vitamins, B12 is not synthesized by animals, fungi, or plants; it is produced exclusively by microorganisms (mainly anaerobes) or archaebacteria in the presence of cobalt.3

- The most frequently occurring natural and active forms of B12 are adenosylcobalamin (also known as coenzyme B12) and methylcobalamin.

- Vitamin B12 is known by several names, depending on its chemical form and usage. The different names for vitamin B12 include:

- Cobalamin:

- This is the general term for compounds having vitamin B12 activity.

- These compounds contain cobalt in a corrin ring.

- Cyanocobalamin:

- This is the synthetic produced form of vitamin B12 commonly found in supplements and fortified foods.

- It is a stable form of the vitamin.

- Inactive form: needs to be metabolized in order to be used by humans.

- Recommended biochemical nomenclature restricts the term “vitamin B12” for cyanocobalamin.4

- Hydroxocobalamin:

- A form of vitamin B12 used in injectable medications, often used to treat vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Inactive form; needs to be metabolized in order to be used by humans.

- Methylcobalamin:

- A natural, bioactive form of vitamin B12 found in food and also available as a supplement.

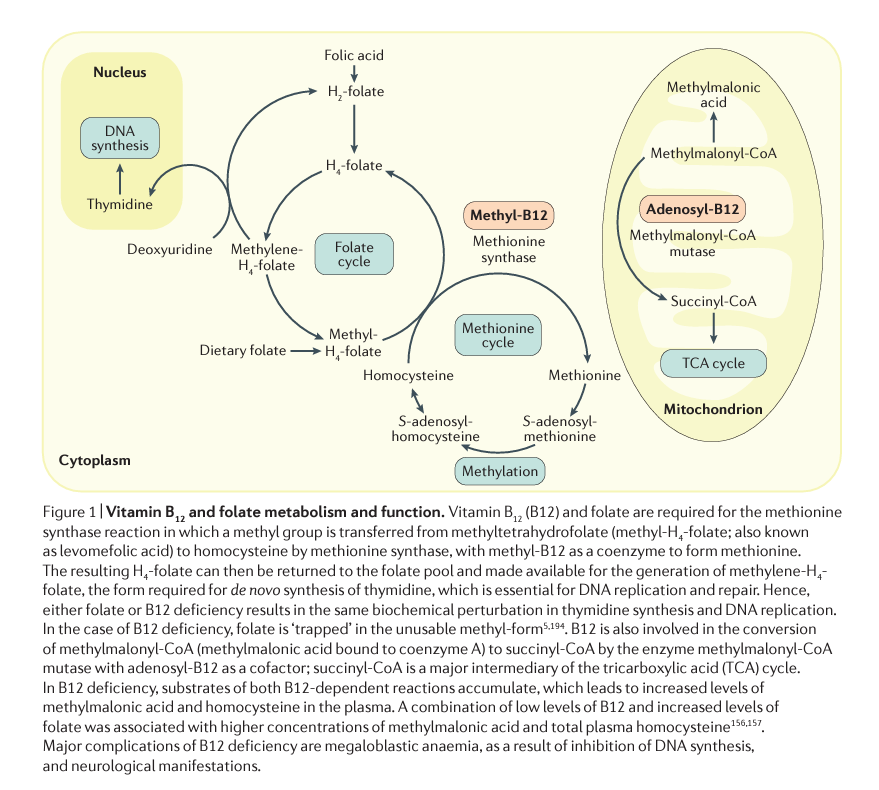

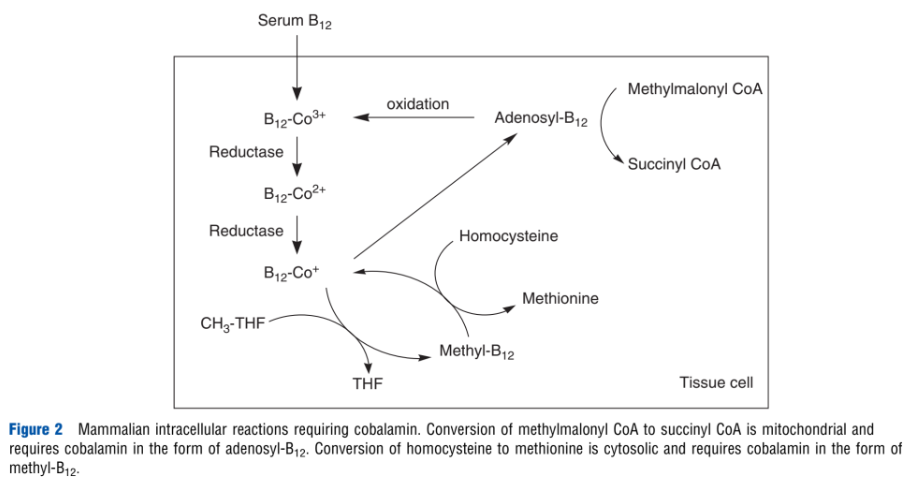

- Functions as a co-enzyme for metabolic reaction required for synthesis of purines and pyrimidines:

- The reaction depends on methyl cobalamin as a co-factor and is also dependent on folate, in which the methyl group of methyltetrahydrofolate is transferred to homocysteine to form methionine and tetrahydrofolate.

- Adenosylcobalamin:

- Another bioactive form of vitamin B12, which plays a role in cellular energy production.

- Functions as a co-enzyme for metabolic reaction; methylmalonyl CoA mutase converts methylmalonyl CoA to succinyl CoA, with 5-deoxy adenosyl cobalamin required as a cofactor.

- Cobalamin:

Function

- Vitamin B12 is an essential cofactor that is integral to methylation processes important in reactions related to DNA synthesis and cell metabolism; thus a deficiency may lead to disruption of DNA synthesis/cell metabolism and have serious clinical consequences.

- Intracellular conversion of vitamin B12 to two active coenzymes, adenosylcobalamin in mitochondria and methylcobalamin in the cytoplasm, is necessary for the homeostasis of methylmalonic acid and homocysteine, respectively.

- Vitamin B12 appears to have only two functions in eukaryotes: as a cofactor for the enzymes:

- Methionine synthase

- MethylmalonylCoA mutase

Sources of vitamin B12

- Vitamin B12 is synthesized by certain bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract of animals and is then absorbed by the host animal.

- Although the intestinal flora of humans is able to synthesize vitamin B12, humans are not able to absorb bacteria-generated vitamin B12 since the location of synthesis (the colon) is too distal from the location of absorption (the small intestine). Therefore, vitamin B12 has to be consumed through food.

- Vitamin B12 is concentrated in animal tissues, hence, vitamin B12 is found only in foods of animal origin.

- Foods that are high in vitamin B12 (µg/100g) include:

- Liver (26–58)

- Beef and lamb (1–3

- Chicken (trace)

- Eggs (1–2.5)

- Dairy foods (0.3–2.4)

- In normal humans the absorption of vitamin B12 from foods has been shown to vary depending on the quantity and type of protein consumed. Vitamin B12 from foods appear to have different absorption rates with better absorption from chicken and beef as compared to eggs.

- There are no naturally occurring bioactive forms of vitamin B12 from plant sources.

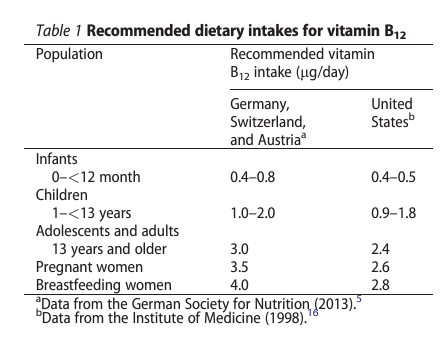

Dietary requirements

- The daily requirement of vitamin B12 has been set at 2.4 μg, but higher amounts — 4 to 7 μg per day — which are common in persons who eat meat or take a daily multivitamin, are associated with lower methylmalonic acid values.5

- As described in the vitamin B12 Dietary Fact Sheet from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the recommended daily intake of vitamin B12 ranges from 0.4 mcg in young infants to 2.4 mcg in adults; slightly higher amounts might be needed during pregnancy and lactation.6

- Total body storage of vitamin B12 ranges from 2 to 5 mg, and approximately half of it is stored in the liver. If vitamin B12 intake ceases, deficiency would usually not develop for at least 1-2 years, sometimes even longer.7

Absorption8

- Active absorption:

- Vitamin B12 is bound to protein in food.

- Vitamin B12 is available for absorption after it has been cleaved from protein by the hydrochloric acid produced by the gastric mucosa.9

- The released cobalamin then attaches to R protein (or R-binder; haptocorrin) and passes into the duodenum where the R protein is removed by pancreatic proteases and free cobalamin binds to intrinsic factor (IF).10

- The IF-cobalamin complex is absorbed by the distal ileum and requires calcium:

- Binds to the cubam receptor in the terminal ileum and is internalized).

- The complex is eventually released from lysosomes and transported across the cell membrane bound to one of two proteins in the blood circulation:

- Haptocorrin, which is responsible for the transport of B12 to the liver.

- Transcobalamin (TC) (he active form of B12).11

- Vitamin B12 enters the circulation about 3–4 hours later bound to TC.

- Excessive vitamin B12 in the circulation, e.g., such as after injections, usually exceeds the binding capacity of TC and is excreted in the urine.

- 1.5–2.0 µg of synthetic vitamin B12 saturates the IF-cobalamin ileal receptors, but other studies have shown higher absorption rates.

- Passive absorption:

Treatment

IM iron

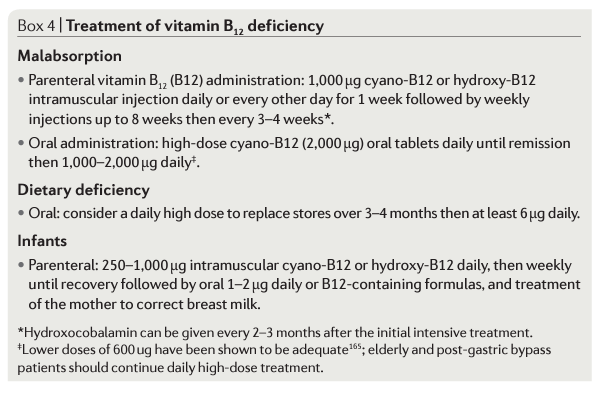

- There are many recommended schedules for injections of vitamin B12 (called cyanocobalamin in the United States and hydroxocobalamin in Europe).14

- About 10% of the injected dose (100 of 1000 μg) is retained; after an intramuscular injection of 1,000 μg of cyanoB12, about 150 μg is ultimately retained in the body 15

- Most vitamin B12-deficient individuals in the UK and other countries are treated with intramuscular vitamin B12, and vitamin B12 replacement has been traditionally administered intramuscularly.

- Intramuscular vitamin B12 can be administered in two different forms: cyanocobalamin and hydroxocobalamin.

- In some countries hydroxocobalamin has completely replaced cyanocobalamin as first choice for vitamin B12 therapy because it is retained in the body longer and can be administered at intervals of up to three months.

- Gastrointestinal absorption barriers of vitamin B12 can be avoided by intramuscular injection.

- Rare side effects: itching, exanthema, chills, fever, hot flushes, nausea, dizziness, and very rarely anaphylaxis.16

Oral iron

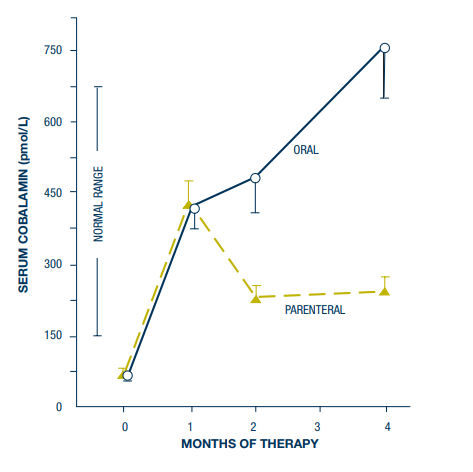

2000 micrograms daily. Parenteral therapy was 9 injections of 1000 micrograms vitamin B12 intramuscularly on days 1,

3, 7, 10, 14, 21, 30, 60 and 90. Bars indicate +/- 1 SEM. At 2 and 4 months, mean serum cobalamin concentrations were

significantly higher with oral therapy (p< 0.001 and p< 0.0005 respectively). Source.

- Despite its widespread availability in most countries and its very safe track record, vitamin B12 is rarely prescribed in the oral form; two exceptions to this are in Canada and Sweden, where in the year 2000 oral vitamin B12 accounted for 73% of the total vitamin B12 prescribed.17

- Possible reasons for doctors not prescribing oral formulations may include a lack of awareness of this option or concerns regarding unpredictable absorption.

- The mechanism for the oral route is based on passive absorption of vitamin B12 (without binding to intrinsic factor) as well as active absorption (following binding to intrinsic factor, if present, e.g. in those patients with dietary deficiency) in the terminal ileum.

- The dose absorption ratio is remarkably constant in an oral dose range from 1 to 100,000 µg of hydroxocobalamin.

- Cyanocobalamin requires conversion to metabolically active cobalamin.

- Advantages of oral form over IM injection:

- Less nursing time on injections

- Less complexity of care

- Less discomfort/pain

- Less bleeding in patients who take anticoagulants

- Less costly according to some analyses

- Disadvantages of oral form over IM injection::

- Greater risk of non-compliance

- In 1991, a survey done on Minneapolis internists led one commentary to conclude that oral vitamin B12 replacement for pernicious anemia was one of “medicine’s best kept secret.”18

- In 1996, when the survey was repeated again in the same area, awareness and use of oral vitamin B12 for pernicious anemia had increased substantially (0–19%), but the majority of doctors still remain unaware of this treatment option (61%).19

- Early studies:

- There were studies in the 1950s and the1960s that showed that oral vitamin B12 could be absorbed by patients with pernicious anemia and could lead to resolution of the anemia.20

- Systematic reviews:

- Oral vitamin B12 replacement for the treatment of pernicious anemia 21

- Relevant articles were identified by PubMed search from January 1, 1980 to March 31, 2016, focusing on patients with pernicious anemia.

- Two randomized controlled trials, three prospective papers, one systematic review, and three clinical reviews fulfilled inclusion criteria.

- In all the five studies, an oral (Delpre’s study via sublingual route) dose of 1000 μg vitamin B12 was used with the exception of Kuzminski’s study, whereby a higher dose of 2000 μg was used.

- Authors: “We found that oral vitamin B12 replacement at 1000 μg daily was adequate to replace vitamin B12 levels in patients with pernicious anemia. We conclude that oral vitamin B12 is an effective alternative to vitamin B12 IM injections. Patients should be offered this alternative after an informed discussion on the advantages and disadvantages of both treatment options.”

- Oral vitamin B12 replacement for the treatment of pernicious anemia 21

| PMID | Study type | Patients | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9694707 | RCT | Newly diagnosed vitamin B12-deficient patients N (total number) = 33 Intervention = 18 (5 had pernicious anemia) Control = 15 (2 had pernicious anemia) 120 days | Oral vitamin B12 2000 μg daily for 120 days vs. intramuscular (IM) vitamin B12 1000 μg on days 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, 21, 30, 60, and 90 | Serum vitamin B12 levels were significantly higher in the oral compared with IM group (643 ± 328 vs. 306 ± 118 pg/mL; p < 0.001) at 2 months. The difference was even greater at 4 months (1005 ± 595 vs. 325 ± 165 pg/mL) |

| 14749150 | RCT | Megaloblastic anemia due to vitamin B12 deficiency N = 60 Intervention = 26 (8 had presence of anti-parietal call antibody) Control = 34 (3 had presence of anti-parietal call antibody) 90 days | Oral vitamin B12 1000 μg daily for 90 days vs. IM vitamin B12 1000 μg daily for 10 days, then once weekly for 28 days and after that continued with once monthly | Serum vitamin B12 levels increased in both groups at 90 days (oral group 213.8 pg/mL and IM group 225.5 pg/mL). There was a statistically significant difference between day 0 and day 90 in both groups (p < 0.0001) but authors did not analyze difference between both groups |

| 10475189 | Prospective | Vitamin B12 deficiency N = 18 (inclusive of patients with pernicious anemia but did not state number) 7–12 days | Sublingual vitamin B12 1000 μg daily for 7–12 days | Normalization of serum vitamin B12 levels was seen in all patients. An increase in vitamin B12 level was as much as fourfold compared with pretreatment in most patients. The mean change of 387.7 pg/mL was statistically significant (p = 0.0001, Student’s t-test) |

| 12743340 | Prospective | Vitamin B12 deficiency N = 40 (10 patients had pernicious anemia) 3–18 months | Loading dose of IM vitamin B12 till vitamin B12 level reached lower 25th centile (418 pg/ mL) and then converted to oral vitamin B12 1000 μg daily | Oral vitamin B12 was effective in all the patients (no patients had to restart IM vitamin B12). At 3 months, the median serum vitamin B12 level was 1193 pg/mL |

| 24672108 | Prospective | Pernicious anemia N=10 | Oral vitamin B12 1000 μg daily for 3 months | After 3 months, serum vitamin B12 levels were increased in all 9 patients (mean increase, 117.4 pg/ mL; p < 0.001). One patient’s result was not available due to technical problem |

- Cochrane Review; Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency 22

- Background: “Vitamin B12 deficiency is common, and the incidence increases with age. Most people with vitamin B12 deficiency are treated in primary care with intramuscular (IM) vitamin B12. Doctors may not be prescribing oral vitamin B12 formulations because they may be unaware of this option or have concerns regarding its effectiveness.”

- Objectives: “To assess the effects of oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency.”

- Selection criteria: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the effect of oral versus IM vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Three RCTs met inclusion criteria (2 included in review discussed above).

- The trials randomized 153 participants (74 participants to oral vitamin B12 and 79 participants to IM vitamin B12).

- Treatment duration and follow-up ranged between three and four months.

- Two trials reported data for serum vitamin B12 levels.

- The overall quality of evidence for this outcome was low due to serious imprecision (low number of trials and participants).

- In two trials employing 1000 μg/day oral vitamin B12, there was no clinically relevant difference in vitamin B12 levels when compared with IM vitamin B12. One trial used 2000 μg/day vitamin B12 and demonstrated a mean difference of 680 pg/mL (95% confidence interval 392.7 to 967.3) in favor of oral vitamin B12.

- No trial reported on clinical signs and symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency, health-related quality of life, or acceptability of the treatment scheme

- Orally taken vitamin B12 showed lower treatment-associated costs than intramuscular vitamin B12 in one trial.

- Authors’ conclusions: Low quality evidence shows oral and IM vitamin B12 having similar effects in terms of normalizing serum vitamin B12 levels, but oral treatment costs less. We found very low-quality evidence that oral vitamin B12 appears as safe as IM vitamin B12. Further trials should conduct better randomization and blinding procedures, recruit more participants, and provide adequate reporting. Future trials should also measure important outcomes such as the clinical signs and symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency, health related-quality of life, socioeconomic effects, and report adverse events adequately, preferably in a primary care setting.”

| PMID | Patients | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14749150 | 60 participants | 1000 μg/day oral or IM vitamin B12 (total dose 15 mg): | MD was -11.7 pg/mL (95% CI -29.5 to 6.1) |

| 9694707 | 33 participants | 2000 μg/day vitamin B12 (total dose 240 mg) or 1000 μg/day IM vitamin B12 | MD was 680 pg/mL (95% CI 392.7 to 967.3) in favor of oral vitamin B12 |

| Gastroenterology 2012;142:S216 | 60 participants | 1000 μg/day oral or IM vitamin B12 (total dose 90 mg and 15 mg, oral and IM respectively) | 27/30 in the IM vitamin B12 group (90%) and 20/30 in the oral vitamin B12 group (66.7%) achieved normalization of serum vitamin B12, defined as ≥ 200 pg/m |

- Clinical practice guidelines

- British Columbia Medical Services Commission (MSC). Cobalamin (vitamin B12) Deficiency – Investigation & Management

- Early treatment of cobalamin deficiency is particularly important because neurologic symptoms may be irreversible.

- Oral crystalline cyanocobalamin (commonly available form) is the treatment of choice. Dosing for pernicious anemia or food-bound cobalamin malabsorption is 1000 mcg/day. In most other cases a dose of 250 mcg/day may be used.

- Oral administration of cobalamin is as effective as parenteral.

- Advantages of oral supplementation are comfort, ease of administration, and cost.

- Parenteral administration should be reserved for those with significant neurological symptoms; It includes 1-5 intramuscular or subcutaneous injections of 1000 mcg crystalline cyanocobalamin daily, followed by oral doses of 1000-2000 mcg/day

- NICE guideline: Vitamin B12 deficiency in over 16s: diagnosis and management:

- Malabsorption as the confirmed or suspected cause of vitamin B12 deficiency:

- Offer lifelong intramuscular vitamin B12 replacement to people if:

- Autoimmune gastritis is the cause

- They have had a total gastrectomy

- They have had a complete terminal ileal resection

- If the person has a vitamin B12 deficiency because of malabsorption that is not caused by autoimmune gastritis, or a total gastrectomy or complete terminal ileal resection (for example, malabsorption caused by coeliac disease, partial gastrectomy or some forms of bariatric surgery):

- Offer vitamin B12 replacement and

- Consider intramuscular instead of oral vitamin B12 replacement.

- When offering oral vitamin B12 replacement to people with vitamin B12 deficiency caused, or suspected to be caused, by malabsorption, prescribe a dosage of at least 1 mg a day.

- Offer lifelong intramuscular vitamin B12 replacement to people if:

- Dietary vitamin B12 2 deficiency

- consider oral vitamin B12 replacement.

- Consider intramuscular vitamin B12 injections instead of oral replacement for suspected or confirmed vitamin B12 deficiency caused by diet if:

- The person has another condition that may deteriorate rapidly and have a major effect on their quality of life (for example, a neurological or hematological condition such as ataxia or anemia).

- There are concerns about adherence to oral treatment, for example, if the person:

- Is older, is or has recently been in hospital and has either multimorbidity or frailty.

- Has delirium or cognitive impairment.

- Is affected by social issues that may prevent them accessing care, such as homelessness.

- Malabsorption as the confirmed or suspected cause of vitamin B12 deficiency:

- BSH Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders:

- Treatment of established cobalamin deficiency should follow the schedules in the BNF (Grade 1A).

- Standard initial therapy for patients without neurological involvement is 1000 mcg intramuscularly (i.m.) three times a week for 2 weeks. The BNF advises that patients presenting with neurological symptoms should receive 1000 mcg i.m. on alternate days until there is no further improvement.

- British Columbia Medical Services Commission (MSC). Cobalamin (vitamin B12) Deficiency – Investigation & Management

- Expert opinion

- Hunt et al23

- Data from randomized controlled trials and observational studies for parenteral treatment are lacking.

- However, the expert consensus for standard treatment in the United Kingdom is to begin parenteral treatment with intramuscular hydroxocobalamin.

- This bypasses the possibility of the debate about whether the treatment will be adequately taken, absorbed, and metabolized.

- Standard initial treatment for patients:

- Without neurological involvement:

- 1000 µg intramuscularly three times a week for two weeks.

- With neurological symptoms:

- 1000 µg intramuscularly on alternate days should be continued for up to three weeks or until there is no further improvement.

- Without neurological involvement:

- If the cause is irreversible then parental therapy should be continued for life.

- National consensus is that there are arguments against the use of oral cobalamin in severely deficient patients and those with malabsorption. High dose oral cobalamin may be a suitable alternative in selective cases, where intramuscular injections are not tolerated and compliance is not a problem.

- Oral treatment may be considered in certain situations—for example, in mild or subclinical deficiency with no clinical features and when absorption and compliance are definitely not a problem.

- Stabler24

- Patients with severe abnormalities should receive injections of 1000 μg at least several times per week for 1 to 2 weeks, then weekly until clear improvement is shown, followed by monthly injections.25

- Treatment of pernicious anemia is lifelong.

- High-dose oral treatment is effective and is increasingly popular.

- Oral doses of 1000 μg deliver 5 to 40 μg, even if taken with food.

- Data are lacking from long-term studies to assess whether oral treatment is effective when doses are administered less frequently than daily.

- Proponents of parenteral therapy state that compliance and monitoring are better in patients who receive this form of therapy because they have frequent contact with health care providers, whereas proponents of oral therapy maintain that compliance will be improved in patients who receive oral therapy because of convenience, comfort, and decreased expense.

- Self-administered injections are also easily taught, economical, and in my experience, effective.

- Patients should be informed of the pros and cons of oral versus parenteral therapy, and regardless of the form of treatment, those with pernicious anemia or malabsorption should be reminded of the need for lifelong replacement.

- Green et al26

- Severe clinical abnormalities should be treated intensively with B12, cyanoB12 or hydroxyB12:

- HydroxyB12 is commonly used in Europe, often at intervals of 2–3 months, as it seems to have better retention than cyanoB12.

- There is no advantage to using the light sensitive forms of cobalamin, such as methylB12 or adenosylB12, instead of the stable cyano or hydroxy forms, which are readily converted in the body into the coenzyme forms, methylB12 and adenosylB12

- High dose oral supplementation is an effective alternative to parenteral treatment.

- Randomized studies of daily high oral doses of 1,000–2,000 μg have shown equivalence or superiority to injected B12.

- Severe clinical abnormalities should be treated intensively with B12, cyanoB12 or hydroxyB12:

- Hunt et al23

- Salinas et al27

- The traditional treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency is the intramuscular injection of cyanocobalamin, generally, 1 mg/d for 1 week, followed by 1 mg/wk for 1 month, and then 1 mg every 1 or2 months ad perpetuum.

- Oral administration of high-dose vitamin B12 (1 to 2 mg daily) is considered as effective as intramuscular administration for correcting anemia and neurologic symptoms.

- Despite many studies suggesting oral administration of vitamin B12 to be easy, effective and less costly than intramuscular administration, debate surrounds the effectiveness of the oral route. This may help explain why it is little used by health professionals.

- In the United States, patients usually receive vitamin B12 injections of 1 mg/d in their first week of treatment; then weekly injections in the following month, and finally monthly injections after that.

- In Denmark, however, patients receive injections of 1 mg cyanocobalamin per week during the first month and every 3 months after that, or 1 mg hydroxycobalamin every other month.