Definition and Overview

Hemolysis is the pathologic accelerated clearance of red blood cells (RBCs) before the end of their normal 120-day lifespan. It can occur within the blood vessels (intravascular) or outside of them and may lead to anemia, reticulocytosis, and release of hemolytic markers. It should be distinguished from normal red cell senescence, which is the physiologic extravascular clearance by macrophages; normal rate of turnover (~1% of RBCs per day). This is not hemolysis, since it is expected, slow, and not associated with lab abnormalities.

Causes/Classification of Hemolysis

Hemolysis can be classified by several schemes according to mechanism, location, or etiology.

- Classical Scheme (immune vs non-immune → intracorpuscular vs extracorpuscular)

- Immune-mediated:

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia:

- Warm

- Cold

- Mixed types

- Alloimmune hemolysis:

- Transfusion reactions

- Hemolytic disease of the newborn)

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia:

- Non-immune mediated:

- Intracorpuscular (RBC-Intrinsic Defects):

- These are problems inherent to the red cell itself (in the membrane, enzymes, or hemoglobin) that make it prone to hemolysis. They are usually inherited. Exceptions include paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), an acquired clonal defect in PIGA gene, and drug-induced oxidant stress on a background of normal G6PD levels.

- Causes include:

- Metabolic/oxidative stress:

- G6PD deficiency (oxidative injury)

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency (energy failure → premature RBC death)

- Oxidant drugs (dapsone, sulfas, nitrofurantoin)1

- Membrane instability:

- Hereditary spherocytosis

- Hereditary elliptocytosis

- Hereditary stomatocytosis

- PNH2

- Hemoglobinopathies:

- Sickle cell disease

- Thalassemia

- Unstable hemoglobin (Hb)

- Other Hb variants

- Metabolic/oxidative stress:

- Extracorpuscular:

- These are factors external to the red cell that damage or destroy otherwise normal RBCs. They include immune-mediated processes, mechanical injury, toxins, and infections. Unlike intracorpuscular causes, they are usually acquired.3

- Causes include:

- Thrombotic microangiopathies (TMA):

- TTP

- HUS

- DIC

- HELLP

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia:

- Cardiac prosthetic valves

- Vascular grafts

- March hemoglobinuria

- Congo drumming

- Infectious:

- Malaria

- Babesiosis

- Clostridial sepsis

- Liver disease:

- Spur cell anemia

- Wilson disease

- Other:

- Thermal injury

- Venoms (snakes, spiders, bees)

- Thrombotic microangiopathies (TMA):

- These are factors external to the red cell that damage or destroy otherwise normal RBCs. They include immune-mediated processes, mechanical injury, toxins, and infections. Unlike intracorpuscular causes, they are usually acquired.3

- Intracorpuscular (RBC-Intrinsic Defects):

- Immune-mediated:

For larger image, click here.

- Classification According to Location (where the RBC is destroyed): Very few hemolytic disorders are purely intravascular or purely extravascular. Most have a mix of both, though one pathway usually predominates:

- Intravascular hemolysis:

- Destruction of RBCs within the circulation/blood vessels → free hemoglobin released into plasma, hemoglobinuria, ↓haptoglobin, ↑LDH):

- Causes include:

- Immune-mediated (acute hemolytic transfusion reactions (ABO incompatibility))

- MAHA (TTP, HUS, DIC, HELLP)

- PNH

- Infections (malaria, clostridia)

- Mechanical trauma (march hemoglobinuria, prosthetic valves)

- Severe G6PD deficiency crises

- Burns (thermal injury)

- Extravascular hemolysis (within spleen/liver macrophages):

- Destruction of RBCs by macrophages in spleen/liver → spherocytes, indirect hyperbilirubinemia, normal/low LDH, no hemoglobinuria.

- Causes include:

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (esp. warm AIHA)

- Hereditary spherocytosis, elliptocytosis

- Hemoglobinopathies (sickle cell, thalassemias)

- Enzyme deficiencies (pyruvate kinase, milder G6PD)

- Hypersplenism

- Intravascular hemolysis:

- Physical Mechanism Scheme:

- Membrane Perforation and Lysis:

- Complement-mediated lysis:

- Formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC, C5b-9) punches holes in the RBC membrane.

- Seen in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), cold agglutinin disease (severe), and transfusion reactions.

- Leads to intravascular hemolysis with release of free Hb, LDH.

- Pore-forming toxins:

- Bacterial hemolysins (e.g. Clostridium perfringens α-toxin) insert into the membrane.

- Cause catastrophic, rapid intravascular hemolysis.

- Complement-mediated lysis:

- Opsonization and Phagocytosis:

- Fc receptor–mediated clearance:

- Antibody-coated RBCs (usually IgG in warm AIHA) engage Fcγ receptors on macrophages.

- Leads to partial “nibbling” (spherocyte formation) or complete engulfment.

- Occurs in spleen/liver → extravascular hemolysis.

- Complement receptor–mediated clearance:

- C3b-opsonized RBCs recognized by complement receptors on macrophages.

- Seen in cold agglutinin disease and some warm AIHA.

- Fc receptor–mediated clearance:

- Mechanical Fragmentation (Shear Stress):

- Prosthetic heart valves and circulatory devices:

- Rigid surfaces and turbulence → shear stress → schistocyte formation.

- Microangiopathic processes (TTP, HUS, DIC, HELLP):

- RBCs shredded on fibrin strands, platelet plugs, and damaged endothelium.

- March hemoglobinuria:

- Repetitive foot-strike trauma damages RBCs in capillaries.

- Prosthetic heart valves and circulatory devices:

- Oxidative and Metabolic Injury:

- Oxidant stress:

- Drugs (dapsone, sulfas), fava beans, infections → excess ROS.

- G6PD deficiency → impaired NADPH → glutathione depletion → Hb oxidation, Heinz bodies, membrane rigidity → splenic bite cells, intravascular hemolysis.

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency:

- ATP depletion → failure of Na⁺/K⁺ pumps → membrane rigidity → splenic clearance.

- Oxidant stress:

- Structural Instability of Hemoglobin:

- Sickle cell disease (SCD):

- HbS polymerizes under deoxygenated states → membrane distortion, sickling.

- Leads to repeated deformation, oxidative injury, and premature clearance (both intra- and extravascular).

- Thalassemia:

- Imbalanced globin chain synthesis → precipitation of excess unmatched chains.

- Causes oxidative membrane damage, ineffective erythropoiesis, and splenic clearance.

- Unstable hemoglobins:

- Prone to denaturation and Heinz body formation → membrane rigidity and hemolysis.

- Sickle cell disease (SCD):

- Infectious Injury:

- Malaria (Plasmodium spp.):

- Parasite replicates inside RBC → physical rupture on schizont release.

- Also marked by immune clearance of parasitized cells.

- Babesiosis:

- Similar intraerythrocytic rupture mechanism.

- Clostridial sepsis:

- Exotoxins directly lyse RBC membranes.

- Malaria (Plasmodium spp.):

- Physical/Chemical Injury:

- Thermal damage

- Hypotonic environments:

- Osmotic swelling and rupture.

- Chemical agents:

- Snake venoms, certain detergents, or chemicals disrupt membrane lipids.

- Accelerated senescence:

- Premature expression of physiologic clearance signals: rigidity, PS exposure, band 3 clustering, natural Ig binding

- “Fast-forwarded senescence” mechanism of hemolysis

- Overlaps with oxidation and energy failure

- Examples include:

- Sickle cell disease → repeated sickling/unsickling accelerates membrane damage → early PS exposure.

- Thalassemia → globin chain imbalance → oxidative injury → band 3 clustering.

- G6PD deficiency → oxidant stress → premature senescent signals.

- Teaching Pearl: Hemolysis can be thought of structurally as:

- Punching holes (complement, toxins).

- Engulfment/nibbling (Fc- or complement-mediated).

- Shredding/shearing (valves, fibrin, platelet plugs).

- Oxidizing/energy failure (G6PD, PK deficiency).

- Hb precipitation/polymerization (thalassemia, SCD, unstable Hb).

- Infection/parasite burst (malaria, babesiosis).

- Physical/chemical burn (heat, toxins, osmotic lysis).

- Membrane Perforation and Lysis:

For larger image, click here.

- Comparing the classical classification scheme with the classification based on physical mechanism:

- Classical scheme (immune vs non-immune → intracorpuscular vs extracorpuscular)

- Question it answers: What is the broad category of the cause?

- It sorts diseases by etiologic mechanism (immune-mediated vs not, inherited vs acquired, intrinsic vs extrinsic to the RBC).

- It’s a diagnostic scaffold: it points you to lab tests and clinical reasoning steps.

- Example: AIHA → “immune” bucket → DAT positive → diagnosis.

- Physical/mechanistic scheme (pores, phagocytosis, shearing, oxidant injury, etc.)

- Question it answers: What is physically happening to the RBC at the moment of destruction?

- It zooms in one level deeper: not just “immune” but how antibodies + complement kill the cell (e.g., MAC pore formation vs Fc receptor–mediated phagocytosis).

- It’s a proximate/mechanistic scaffold: it abstracts the endgame pathways of RBC death.

- Example: AIHA → “phagocytosis/nibbling” spoke; PNH → “pore formation” spoke.

- Take home:

- Classical = etiologic / diagnostic classification (broad cause, useful at bedside).

- Physical = proximate / mechanistic classification (structural pathway, useful conceptually).

- Both = complementary layers:

- Classical tells you who the culprit is (immune system? RBC gene defect? outside trauma?).

- Physical tells you how the RBC is actually killed (engulfed, punched, shredded, oxidized).

- Classical scheme (immune vs non-immune → intracorpuscular vs extracorpuscular)

Hemolysis Mimics

Conditions where red cell breakdown products appear elevated (LDH, bilirubin, low haptoglobin), but the process is not classical hemolysis of intact circulating RBCs:

- Hematoma resorption: Extravasated RBCs broken down by tissue macrophages → lab pattern similar to hemolysis.

- HLH (hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis): Activated macrophages engulf circulating RBCs (and other hematopoietic cells), producing a hemolysis-like lab profile, though the mechanism is immune dysregulation rather than primary RBC pathology.

- Intramedullary cell death / ineffective erythropoiesis. Megaloblastic erythroid precursors in the marrow undergo intramedullary apoptosis/lysis before they can mature. This releases LDH and indirect bilirubin, and lowers haptoglobin, mimicking hemolysis. But unlike classical hemolysis, the red cells never reach circulation → sometimes called “intramedullary hemolysis,” though it’s really ineffective erythropoiesis.4

From Cell Lysis to Lab Findings

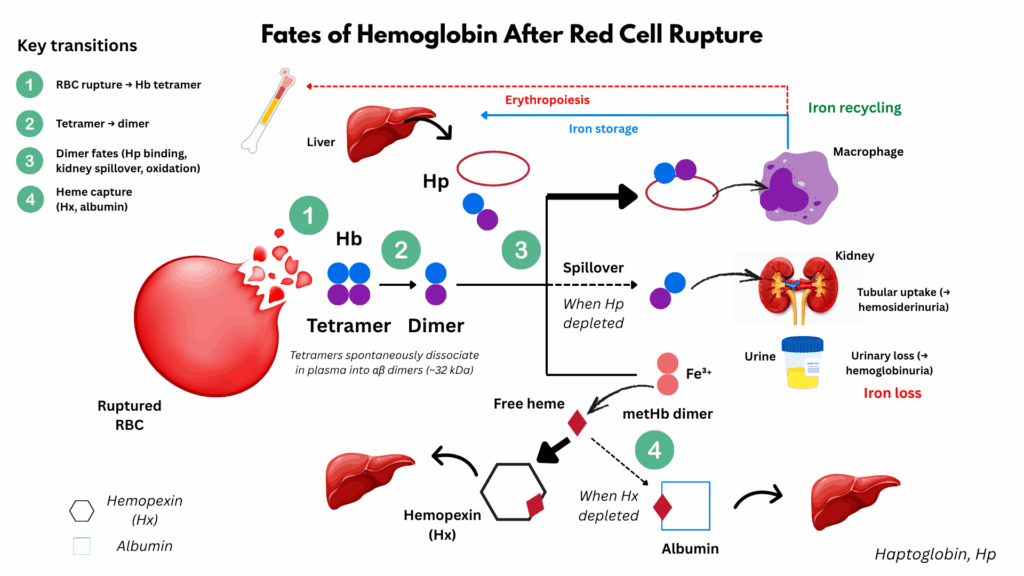

When a red blood cell is destroyed, the story doesn’t end with its rupture. What follows are predictable biochemical and physiological events—the release of hemoglobin and other cell contents, their binding and clearance pathways, and the downstream effects on bilirubin metabolism, iron handling, and the kidneys.

This section will focus on those post-lysis consequences, because they form the basis for interpreting the laboratory findings of hemolysis. In other words, we’re shifting from why RBCs break (classification) to what happens after they break (consequences and lab correlations).

- Intravascular hemolysis: RBCs lyse directly in circulation, releasing:

- Hemoglobin:

- RBC lysis and release of hemoglobin:

- In intravascular hemolysis, RBC membranes rupture directly in the circulation.

- This releases tetrameric hemoglobin (α₂β₂) into plasma.

- The tetramer is unstable and quickly dissociates into αβ dimers (much smaller and freely diffusible).

- Binding to haptoglobin:

- These αβ dimers are immediately bound by haptoglobin (Hp), a plasma glycoprotein.

- The Hb–Hp complex:

- Prevents renal filtration of Hb dimers.

- Directs the complex to macrophages (mostly Kupffer cells in the liver).

- Receptor: CD163 (on macrophages/monocytes) recognizes Hb–Hp.

- Fate: Complex is endocytosed and degraded.

- Haptoglobin is not recycled → serum haptoglobin becomes depleted in active intravascular hemolysis.

- Hemoglobin → split into globin chains (broken down to amino acids) and heme.

- Heme metabolism inside macrophages:

- Free heme is degraded by heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1).

- Reaction: heme → biliverdin + Fe²⁺ + CO.5

- Biliverdin is then converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase.

- Bilirubin is released into plasma → bound to albumin → transported to liver for conjugation.

- Free heme is degraded by heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1).

- When Hp is saturated:

- Free Hb dimers circulate.

- These small dimers are filtered by the kidney → hemoglobinuria + renal tubular uptake → hemosiderinuria.

- They are not broken down into heme first before filtration; the whole Hb dimer spills into urine.

- Oxidative breakdown of Hb:

- Free Hb dimers in plasma are unstable. They undergo auto-oxidation (Hb → metHb → release of free heme).

- This results in free heme in circulation.

- Handling of free heme:

- Free heme is tightly bound by hemopexin, another hepatocyte-derived plasma glycoprotein.

- The heme–hemopexin complex is cleared by hepatocytes via the CD91 (LRP1) receptor.

- This protects tissues from heme’s pro-oxidant toxic

- If hemopexin is depleted, heme binds albumin (methemalbumin).

- These complexes are too large to be filtered → remain in plasma, cleared by hepatocytes.

- The “fork” between Hb dimeruria and heme binding (to hemopexin/albumin) depends on a few interrelated factors:

- Concentration of free Hb dimers in plasma:

- At low-to-moderate levels (once Hp is saturated but not massively overloaded), Hb dimers remain intact long enough to be filtered by the kidney → hemoglobinuria.

- At higher concentrations and longer residence times, Hb dimers undergo oxidation (Hb → metHb) and release heme → which is then captured by hemopexin or albumin.

- Rate of auto-oxidation:

- Hb in plasma is outside its natural reducing environment (no NADH–metHb reductase, no catalase, no GSH-rich cytosol).

- So it auto-oxidizes faster than inside RBCs → metHb formation → free heme release.

- The faster this occurs, the more heme (not intact Hb) ends up in circulation.

- Scavenger availability:

- Hp present → Hb dimers are stabilized and cleared before they oxidize.

- Hp depleted but hemopexin available → free heme released from oxidized Hb is rapidly bound by hemopexin.

- If both Hp and hemopexin are saturated, heme transfers to albumin (methemalbumin).

- If even albumin buffering is exceeded → free Hb/HEME spillover increases risk of renal injury.

- Kidney filtration dynamics:

- Hb dimers are freely filterable (32 kDa).

- If plasma levels rise acutely, dimers reach the glomerulus before substantial oxidative degradation occurs → hemoglobinuria dominates.

- If levels rise more chronically or subacutely, there is more time for oxidation → more heme is liberated and diverted into the hemopexin/albumin pathway.

- Key point:

- Acute / rapid intravascular hemolysis → overwhelms Hp → intact Hb dimers appear in urine.

- Slower / sustained hemolysis → allows Hb to oxidize in plasma → heme is released and bound by hemopexin or albumin, reducing renal Hb excretion.

- Concentration of free Hb dimers in plasma:

- Free Hb dimers circulate.

- Renal handling of hemoglobin dimers:

- When both haptoglobin is saturated, free Hb dimers remain in circulation.

- These dimers are small enough to be filtered at the glomerulus.

- Receptor: They are reabsorbed in the proximal tubule via the megalin–cubilin receptor complex.6

- If the reabsorptive capacity is exceeded:

- Free hemoglobin appears in urine (hemoglobinuria).

- Renal tubular cells accumulate iron as hemosiderin, later detectable as hemosiderinuria.

- RBC lysis and release of hemoglobin:

- Hemoglobin:

For larger image, click here.

- Intravascular hemolysis (cont’d):

- Enzymes:

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH):

- Role in RBCs:

- RBCs rely entirely on anaerobic glycolysis (no mitochondria).

- LDH catalyzes the interconversion:

- Pyruvate+NADH↔Lactate+NAD+

- This regenerates NAD⁺, which is essential to keep glycolysis running.

- Abundance in RBCs:

- RBCs are packed with LDH (especially LDH-1 and LDH-2 isoenzymes).

- On a per-cell basis, RBCs contain far more LDH than most other circulating cells.

- This is why LDH is a very sensitive marker of hemolysis; even small-scale lysis releases a lot into plasma.

- After release:

- LDH enters plasma, where it is measured as total LDH activity.

- Plasma half-life is ~24 hours; taken up by the liver.

- Elevated LDH is not specific to hemolysis (can also come from liver, muscle, or malignancy), but in the right context, it’s a strong marker.

- Role in RBCs:

- Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST):

- Role in RBCs:

- Contributes to amino acid and nucleotide metabolism.

- Helps maintain redox balance by supporting NAD⁺/NADH cycling.

- Abundance in RBCs:

- RBCs contain a relatively high concentration of AST compared to ALT.

- This contributes to the AST >> ALT ratio seen in hemolysis.

- While hepatocytes have much more AST in absolute terms, RBCs are the dominant non-hepatic source.

- After release:

- AST is released into plasma.

- Unlike LDH, it has a shorter plasma half-life (~12–18 hours); cleared mostly by the liver.

- Elevation is modest compared to LDH, but the AST:ALT ratio can be a clue.

- Other causes of increased AST:ALT ratio include:

- Alcoholic liver disease

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Myocardial infarction

- Role in RBCs:

- Beyond LDH and AST: What Else is Released?

- When red cells rupture, thousands of intracellular molecules are liberated into circulation, including:

- Cytosolic enzymes:

- Glycolytic enzymes (aldolase, enolase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, pyruvate kinase).

- Pentose phosphate pathway enzymes (G6PD, transketolase, transaldolase).

- Others with potential biomarker value but rarely measured clinically.

- Metabolites:

- ATP, ADP, AMP, 2,3-BPG, glutathione.

- These can influence vascular tone (ATP, ADP → purinergic signaling) and oxygen affinity (2,3-BPG).

- Membrane proteins and lipids:

- Band 3, spectrin, ankyrin, glycophorins, and phosphatidylserine-exposing fragments.

- Some of these are unique to RBCs and could serve as specific biomarkers.

- Cytosolic enzymes:

- Lineage-restricted molecules — not widely expressed in other cells. Examples:

- Band 3 (anion exchanger 1)

- Glycophorin A

- Spectrin and ankyrin complexes

- Potential biomarker candidates:

- Could provide more specific and sensitive markers of hemolysis than LDH or AST, which are ubiquitous in other tissues.

- For example, plasma glycophorin A fragments might reflect hemolysis more specifically than LDH but aren’t clinically used yet.

- When red cells rupture, thousands of intracellular molecules are liberated into circulation, including:

- Why LDH and AST Became the Classics:

- They are abundant in RBCs.

- Simple, cheap assays became available early on.

- Clinicians learned to interpret them in context.

- But they are not specific to RBCs (LDH is in virtually all tissues including muscle, liver, tumors; AST in liver, muscle, heart).

- Teaching Pearl:

- Hemolysis floods plasma with a vast array of RBC-derived proteins, metabolites, and membrane fragments. LDH and AST are just the tip of the iceberg. Many RBC-specific proteins could, in theory, serve as more specific biomarkers of hemolysis, but they are not yet widely applied clinically.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH):

- Intravascular hemolysis summary:

- Free Hb:

- → haptoglobin → CD163 uptake → degradation → bilirubin/CO.

- Hemopexin handling of free heme.

- Renal handling of Hb dimers → reabsorption → hemoglobinuria if overloaded.

- Enzyme release:

- Enzyme release

- LDH and AST as classic examples.

- Thousands of other molecules (potential future biomarkers).

- Free Hb:

- Enzymes:

- Extravascular hemolysis: RBCs removed by macrophages in spleen/liver:

- Intact RBCs are engulfed by macrophages.

- Hemoglobin is degraded intracellularly, along the same pathways as Hb–Hp complexes, resulting in predominant increase in indirect bilirubin.

- The process is largely contain:

- Small amounts of hemoglobin escape into plasma, resulting in reduction in haptoglobin.7

- LDH and other cytosolic enzymes can leak into circulation, resulting in modest elevations of LDH.

- Overlap: Many hemolytic disorders have both components; the intra/extravascular distinction is not always clear-cut.

- For example:

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is “extravascular” because macrophages nibble or engulf antibody-coated RBCs but complement activation can cause some intravascular lysis.

- PNH is “intravascular” because of MAC formation, but chronic complement opsonization also leads to extravascular clearance.

- In microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), RBCs fragment (intravascular) but are also cleared by macrophages (extravascular).

- In malaria, parasite rupture causes intravascular release, but infected cells are also recognized and phagocytosed.

- Why the overlap?

- The fate of an RBC depends on where and how it’s injured:

- Mild surface damage → macrophages detect and remove it (EVH).

- Severe membrane rupture → immediate intravascular hemolysis.

- Complement, mechanical stress, and antibody burden can tip the balance in either direction.

- The fate of an RBC depends on where and how it’s injured:

- For example:

Laboratory Findings

- Directly Released by RBCs (cytosolic or membrane contents) (primary “cytosolic leak” markers):

- Release of cytosolic contents from RBCs, including:8

- Hemoglobin → free Hb dimers in plasma

- LDH (especially LDH-1, LDH-2 isoforms)

- AST (lower levels compared with LDH, but still released)

- Carbonic anhydrase (minor, not routinely measured)

- Potassium (rarely clinically relevant except in severe acute hemolysis or storage lesions)

- These markers arise most dramatically when red cells rupture directly in plasma (intravascular hemolysis), but may also increase to a lesser degree from macrophage digestion of intact cells (extravascular hemolysis):

- Intravascular hemolysis

- RBCs rupture directly in the circulation.

- Cytosolic contents spill immediately into plasma.

- Leads to sharp elevations in LDH, free Hb, AST, K⁺.

- Leak from macrophages (after engulfment of intact RBCs in extravascular hemolysis)

- RBCs are digested in phagolysosomes.

- Some cytosolic components (LDH, AST) can “leak” or be released during processing.

- Elevations tend to be smaller/milder, but still measurable.

- Intravascular hemolysis

- Summary: Reflects the release of RBC cytoplasm; elevations are most dramatic in intravascular hemolysis but may also arise secondarily from macrophage digestion.

- Release of cytosolic contents from RBCs, including:8

- Products of macrophage processing of RBCs (extravascular hemolysis) (secondary metabolic byproducts of RBC destruction):

- When intact red cells are engulfed, hemoglobin is catabolized through the heme oxygenase pathway:

- Indirect (unconjugated) bilirubin (heme → biliverdin → bilirubin)

- Iron (stored in ferritin/hemosiderin, recycled via transferrin)

- Carbon monoxide (from heme oxygenase activity; not usually measured clinically except in special settings like neonatal jaundice studies or research)

- Summary: Secondary metabolic byproducts of RBC destruction; these dominate in extravascular hemolysis.

- When intact red cells are engulfed, hemoglobin is catabolized through the heme oxygenase pathway:

- “Scavenger system” markers (host response, bridging both processes):

- Not directly from RBCs or macrophages, but from host proteins handling hemoglobin/heme overflow:

- Haptoglobin (↓ as it binds free Hb)

- Hemopexin (↓ as it binds free heme)

- Methemalbumin (heme bound to albumin when hemopexin depleted)

- Summary: Reflects the host’s defense and clearance system for free Hb and heme; depletion is most striking in intravascular hemolysis.

- Not directly from RBCs or macrophages, but from host proteins handling hemoglobin/heme overflow:

- Products of renal handling of hemolysis byproducts (urinary markers):

- When plasma concentrations of hemoglobin/heme exceed binding and clearance capacity, the kidney filters and metabolizes them:

- Hemoglobinuria (free Hb dimers filtered → red/brown urine; dipstick positive for blood but no RBCs on microscopy)

- Hemosiderinuria (renal tubular cells take up Hb → convert iron to hemosiderin → sloughed in urine; marker of chronic intravascular hemolysis)

- Urobilinogen (excess bilirubin from macrophage processing → increased enterohepatic circulation → more urobilinogen excreted in urine)

- Summary: Reflects renal excretion and tubular processing of hemolysis products; most prominent in intravascular hemolysis but urobilinogen also rises with extravascular pathways.

- When plasma concentrations of hemoglobin/heme exceed binding and clearance capacity, the kidney filters and metabolizes them:

Hemolytic markers in intravascular and extravascular hemolysis

| Marker | Intravascular Hemolysis (e.g., PNH, MAHA, mechanical valves) | Extravascular Hemolysis (e.g., Hereditary spherocytosis, Warm AIHA) | Mixed/Overlap (Malaria, SCD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDH | ↑↑↑ | ↑ (variable)* | ↑↑ |

| Indirect bilirubin | ↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑ |

| Haptoglobin | ↓↓↓ (often 0) | ↓ / normal | ↓↓ |

| Plasma free Hb | ↑↑↑ | – | ↑ |

| Hemoglobinuria*** | Present | – | Possible |

| Hemosiderinuria | Present (chronic IVH) | – | Possible |

| Urobilinogen**** | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ |

| Reticulocytes | ↑↑** | ↑↑** | ↑↑** |

| Peripheral smear | Schistocytes, ghosts | Spherocytes, polychromasia | Sickle cells, bite cells, |

- Summary of changes in hemolytic markers:

- Cytosolic enzyme release:

- ↑ LDH, ↑ AST (RBC-rich enzymes).

- Hemoglobin handling:

- ↓ Haptoglobin (binds free Hb, cleared by macrophages).

- Plasma Hb (specific but rarely measured).

- ↑ Indirect bilirubin (heme breakdown).

- Urine changes:

- Hemoglobinuria: dipstick positive for blood but no RBCs.

- Hemosiderinuria: from renal tubular cell sloughing.

- Urobilinogen: elevated on dipstick.

- Bone marrow response:

- ↑ Reticulocyte count (unless impaired response).

- Cytosolic enzyme release:

- Comparison of “hemolysis markers” in different conditions:9

‘Hemolytic markers’ beyond hemolysis: cirrhosis, B12 deficiency, hematoma

| Marker | Hemolytic Anemia (IVH/EVH) | Cirrhosis/Liver disease | B12 Deficiency (Ineffective erythropoiesis) | Hematoma/Resorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDH | ↑↑ (esp. in intravascular) | ↑ (from hepatocyte injury) | ↑↑↑ (very high, due to intramedullary hemolysis) | ↑ (local RBC breakdown) |

| Indirect bilirubin | ↑ (esp. in extravascular) | ↑ (impaired conjugation, shunting) | ↑ (from ineffective erythropoiesis) | ↑ (heme breakdown in tissue) |

| Haptoglobin | ↓ (consumed by free Hb in IVH) | ↓ (reduced hepatic synthesis) | Normal / mildly ↓ (not a major feature) | Normal / mildly ↓ |

| Plasma free Hb | ↑↑ (in intravascular) | – | – | – |

| Hemoglobinuria | Present in IVH | – | – | – |

| Hemosiderinuria | Present in chronic IVH | – | – | – |

| Urobilinogen (urine) | ↑ | ↑ (poor hepatic clearance) | ↑ (secondary to bilirubin turnover) | ↑ |

| Reticulocytes | ↑ (if marrow intact) | Variable (often ↓ if marrow suppressed by liver disease) | Normal or ↓ (marrow ineffective, doesn’t release mature cells) | – |

| Peripheral smear | Schistocytes, spherocytes, sickle cells, etc. (depending on cause) | Target cells, acanthocytes | Macrocytosis, hypersegmented neutrophils | Normal RBC morphology |

| How diagnosis is made | Hemolysis labs + smear morphology + DAT (if immune) | Clinical context, LFTs, imaging, biopsy | Macrocytosis, megaloblasts, B12/folate levels | Clinical history (trauma, surgery), imaging, physical exam |

Teaching Pearls:

- Overlap: LDH and bilirubin rise in all four, but for different reasons. Context is key.

- Haptoglobin: Low both in hemolysis (consumption) and cirrhosis (reduced synthesis).

- B12 deficiency: Looks like “hemolysis” because of intramedullary RBC destruction (ineffective erythropoiesis) — LDH and indirect bilirubin can be as high or higher than in classic hemolysis.

- Hematoma: Local RBC breakdown outside vessels can mimic hemolysis labs (bilirubin ↑, LDH ↑, urobilinogen ↑), but no hemoglobinemia/hemoglobinuria.

Clinical Features

Symptoms depend on acuity, severity, and cause.

- General anemia symptoms: fatigue, pallor, dyspnea, tachycardia.

- Hemolysis-specific:

- Jaundice (indirect bilirubin).

- Dark urine (hemoglobinuria).

- Splenomegaly (extravascular).

- Gallstones (pigment stones in chronic hemolysis).

- Intravascular crisis: fever, chills, back pain, hemoglobinuria.

Complications

Ongoing hemolysis can lead to secondary problems.

- Pigment gallstones (bilirubin stones).

- Pulmonary hypertension (especially in sickle cell disease).

- Aplastic crisis (parvovirus B19 infection).

- Iron overload (from repeated transfusions).

- Renal dysfunction (from hemoglobinuria).

Diagnostic Approach

HHemolysis should be considered when anemia is unexplained or when clinical clues such as jaundice, dark urine, or splenomegaly are present. The approach relies on demonstrating accelerated RBC destruction, marrow response, and then narrowing to the mechanism and etiology. Importantly, hemolysis can sometimes be compensated, with normal hemoglobin due to robust reticulocytosis, and many other conditions can mimic “hemolysis markers.” Integration of clinical context is therefore essential.

- Confirm or exclude anemia:

- CBC: Hb/Hct may be low, but not always.

- ⚠️ Compensated hemolysis: normal Hb with elevated retics and subtle lab footprint.

- MCV and indices (may suggest underlying disorder, e.g., HS with high MCHC, macrocytosis if retics high)

- Look for evidence of increased RBC destruction:

- ↑ LDH (especially in intravascular hemolysis)

- ↑ Indirect (unconjugated) bilirubin

- ↓ Haptoglobin (consumption or decreased synthesis)

- Plasma free Hb (intravascular)

- Assess marrow response:

- Reticulocytosis (expected if marrow intact)

- Absent or blunted retic rise → consider marrow disease, nutrient deficiency, or recent onset

- Evaluate urinary findings (esp. intravascular hemolysis):

- Hemoglobinuria (Hb dipstick +, no RBCs on microscopy)

- Hemosiderinuria (chronic IVH)

- ↑ Urobilinogen

- Review the peripheral smear:

- Schistocytes → MAHA, mechanical hemolysis

- Spherocytes → HS, warm AIHA

- Bite cells/Heinz bodies → G6PD deficiency

- Sickle cells, parasites, agglutination → specific clues

- Distinguish immune vs non-immune causes:

- Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT/Coombs): positive in AIHA, transfusion reaction, drug-induced

- Negative DAT: consider membrane defects, enzymopathies, mechanical causes, infections

- Identify underlying etiology:

- Membrane disorders (HS, PNH)

- Enzyme defects (G6PD, PK deficiency)

- Hemoglobinopathies (SCD, thalassemia)

- Extrinsic causes (immune, mechanical, microangiopathic, infection, toxins)

- Rule out mimics (“pseudo-hemolysis”):

- Cirrhosis/liver disease → high indirect bilirubin, low haptoglobin (from ↓ synthesis), high LDH (from hepatocytes)

- Vitamin B12 deficiency → ineffective erythropoiesis (intramedullary “hemolysis”), very high LDH, high indirect bilirubin but no reticulocytosis

- Large hematoma resorption → bilirubin and LDH elevation, but no hemoglobinuria/reticulocytosis

- Teaching pearl: Always ask, “Is this true hemolysis or just a mimic?”

- Teaching points:

- The diagnostic approach to hemolysis isn’t just about checking “hemolysis labs.” It’s about combining destruction evidence + marrow response + mechanism-specific clues to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

- Hemolysis may present with normal Hb if compensated — look for retics and labs of turnover.

- Not all abnormal “hemolysis markers” equal hemolytic anemia — always keep mimics in the workflow.

Management Principles

Treatment depends on the underlying cause.

- General supportive:

- Treat anemia (transfusions if needed).

- Folate supplementation.

- Monitor/avoid triggers (oxidant drugs in G6PD deficiency).

- Targeted therapy:

- AIHA → steroids, immunosuppression, rituximab, splenectomy.

- Thalassemia, sickle cell → disease-specific protocols.

- MAHA → treat underlying cause (TTP, DIC, etc.).

- Infections → appropriate antimicrobials.

- Complication management:

- Iron chelation for transfusion overload.

- Cholecystectomy for gallstones if symptomatic.

Key Teaching Pearls

- Not all hemolytic markers reflect the same process — LDH/AST = cell lysis, bilirubin = heme breakdown, haptoglobin = Hb binding.

- Intravascular vs. extravascular is a helpful framework, but most conditions show overlap.

- Always interpret hemolysis labs in clinical context — mimics (ineffective erythropoiesis, resolving hematoma, HLH) can produce “hemolysis profiles” without true RBC destruction in circulation.

For quiz, click here

Frequently Asked Questions

Tutorial: Hemolysis

Yes. Haptoglobin is an acute-phase reactant and can be falsely elevated in inflammation, masking the consumption from hemolysis. In addition, very mild or intermittent hemolysis may not overwhelm haptoglobin clearance.

Yes. In “compensated hemolysis,” the bone marrow increases red blood cell production enough to keep hemoglobin normal despite ongoing hemolysis.

Yes. Clostridial sepsis (via α-toxin), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (cold agglutinins), and Babesia (intraerythrocytic parasite) can all cause hemolysis through direct RBC destruction or immune mechanisms.

The diagnosis is based on a combination of:

- Clinical suspicion (e.g., anemia, jaundice, dark urine)

- Laboratory markers (LDH, haptoglobin, bilirubin, reticulocyte count)

- Exclusion of mimics

- Additional testing (DAT, peripheral smear, genetics, etc.) to determine the cause.

Malaria parasites rupture RBCs during their asexual cycle (direct destruction). Additionally, infected and uninfected RBCs are cleared by splenic macrophages due to altered membrane properties and immune recognition.

Common markers include:

- ↑ LDH (especially intravascular hemolysis)

- ↓ Haptoglobin

- ↑ Indirect bilirubin

- ↑ Reticulocyte count

- Hemoglobinuria/hemosiderinuria (in intravascular cases)

Cirrhosis, severe vitamin B12 deficiency, and resolving hematomas can all cause elevated indirect bilirubin or LDH that may resemble hemolysis.

Hemolysis is the premature destruction of red blood cells. It can occur inside blood vessels (intravascular) or in the spleen and liver (extravascular).

The DAT detects immunoglobulin and/or complement coating the RBC surface. A positive test supports immune-mediated hemolysis (e.g., warm or cold autoimmune hemolytic anemia), while a negative DAT suggests non-immune causes.

- Hemolysis: reticulocytosis, low haptoglobin, hemoglobinuria (if intravascular).

- Cirrhosis: may raise indirect bilirubin but typically without low haptoglobin or reticulocytosis.

- B12 deficiency: can elevate LDH and indirect bilirubin due to intramedullary RBC death, but smear shows macrocytosis and hypersegmented neutrophils.

The liver has a high capacity to conjugate bilirubin. In chronic or slowly progressive hemolysis, hepatic clearance can keep pace, preventing hyperbilirubinemia despite ongoing RBC destruction.

Narrow, fibrin-rich microvascular channels slice RBCs as they pass, producing fragmented cells (schistocytes) and intravascular hemolysis.

Free hemoglobin is released directly into plasma when RBCs lyse intravascularly. Once haptoglobin is saturated, unbound hemoglobin dimers are filtered by the kidney, appearing in urine. In extravascular hemolysis, intact RBCs are phagocytosed, so hemoglobin is not released directly into circulation.

Red cells are physically traumatized as they pass through turbulent flow or strike the prosthetic surface. This shear stress fragments cells, producing schistocytes and causing intravascular hemolysis.

PNH RBCs lack GPI-anchored proteins that protect against complement. This makes them highly susceptible to complement-mediated lysis in circulation, leading to chronic intravascular hemolysis, hemoglobinuria, and risk of thrombosis.

Severe B12 deficiency leads to ineffective erythropoiesis (intramedullary destruction of RBC precursors). This raises LDH and indirect bilirubin, mimicking hemolysis, but haptoglobin is usually normal and the smear shows macrocytosis with hypersegmented neutrophils.

In intravascular hemolysis, red cells rupture directly in circulation, releasing large amounts of cytosolic LDH into plasma. In hereditary spherocytosis (extravascular), intact RBCs are engulfed and digested by macrophages, so LDH remains contained within the macrophage and is not markedly elevated.

Infections generate oxidative stress through activated neutrophils and cytokines. In G6PD deficiency, RBCs cannot regenerate NADPH effectively, so oxidant damage accumulates, leading to hemolysis.

References

- Krishnadasan R. Hemolytic Anemias: Autoimmune and Beyond. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2021 Apr 1;12(3):337–340.

- Robertson JJ et al. The Acute Hemolytic Anemias: The Importance of Emergency Diagnosis and Management. J Emerg Med. 2017 Aug;53(2):202-211.

- Philips J and Henderson AC. Hemolytic Anemia: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2018 Sep 15;98(6):354-361.

- Barcellini W, Fattizzo B. Clinical Applications of Hemolytic Markers in the Differential Diagnosis and Management of Hemolytic Anemia. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:635670