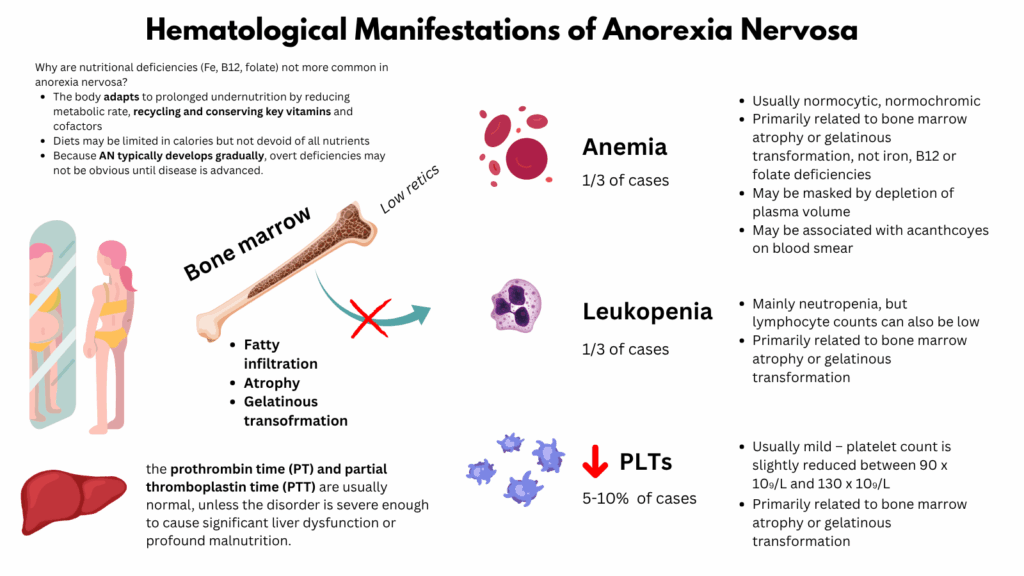

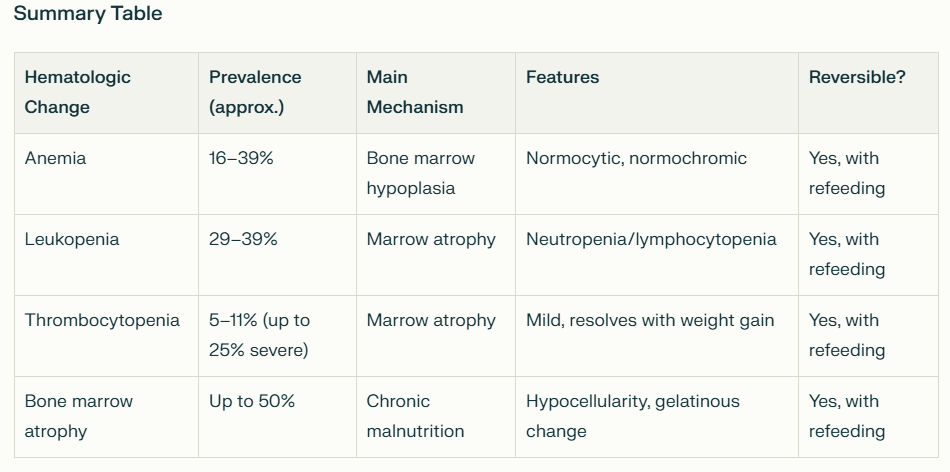

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a complex psychiatric disorder with profound systemic and hematologic effects, due to bone marrow suppression and to a lesser extent nutritional deficiency and hormonal dysregulation. Hematologic manifestations are common and can serve as key indicators of disease severity and chronicity. The most common hematological changes include:

- Mild normocytic, normochromic anemia

- Leukopenia (often with relative lymphocytosis)

- Less frequently, thrombocytopenia

These cytopenias are primarily due to chronic protein-energy malnutrition, which leads to bone marrow atrophy and, in severe cases, gelatinous marrow transformation.

- The degree of cytopenia correlates with the severity and duration of malnutrition and total body fat mass depletion.

- Pancytopenia can occur in severe or prolonged cases

- These abnormalities typically resolve with nutritional rehabilitation

Anemia:

- Seen in about 16–39% of patients.1

- Most commonly normocytic, normochromic; sometimes microcytic or macrocytic depending on specific deficiencies.

- Usually due to bone marrow hypoplasia (reduced bone marrow cell production), rather than pure iron or vitamin deficiencies, though deficiency of iron, vitamin B12, or folate can rarely contribute.

- Iron deficiency is not a typical finding in patients with AN, especially not in female patients. This is most likely due to the frequent occurrence of secondary amenorrhea resulting in a reduced iron loss in these patients. In one study 33% of the patients demonstrated an elevated level of serum ferritin.2

- Depletion of plasma volume (consequence of extracellular volume depletion, due to salt and water deficits caused by the malnutrition) may conceal the severity of an anemia.3

| Type | Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Normocytic normochromic anemia | Most common; due to bone marrow suppression and decreased erythropoiesis |

| Microcytic anemia | Iron deficiency from poor intake, menstrual irregularities, or GI losses |

| Macrocytic anemia | Less common; due to folate or vitamin B12 deficiency |

- Low reticulocyte count due to hypoproliferation

- Often mild to moderate in severity

- May coexist with leukopenia and thrombocytopenia (pancytopenia)

- May be associated with acanthocytosis on peripheral smear (rapidly dis-appears during the refeeding process)

- Acquired hemolytic syndrome may develop secondary to hypophosphatemia during the refeeding process4

Leukopenia:

- The most common hematologic abnormality (29–39% of patients).

- Mainly neutropenia, but lymphocyte counts can also be low.

- Severe cytopenias with a granulocyte count below 0.5 x 109/L are uncommon.

- Leukocytopenia is more frequent in AN-patients who are strict dieters than in those who vomit or purge (36% vs. 10%).5

- Primarily related to bone marrow atrophy or gelatinous transformation (replacement of cellular marrow with fat and glycosaminoglycans). Bone marrow hypoplasia leads to reduced myeloid precursors.

- Infection risk is surprisingly low, possibly due to preserved immune function despite low counts.

Thrombocytopenia:

- Seen in 5–11% overall, but up to 25% in cases of severe anorexia.

- Usually mild – platelet count is slightly reduced between 90 x 109/L and 130 x 109/L

- Significant bleeding is rare

- May result from global marrow suppression or nutritional deficiencies

Pancytopenia:

- In severe or prolonged starvation

- May be a sign of bone marrow atrophy or gelatinous marrow transformation

- Bone marrow biopsy may show:

- Hypocellularity

- Fatty infiltration

- Gelatinous transformation (replacement of hematopoietic tissue with mucopolysaccharide-rich material)

Coagulation Abnormalities:

- Prolonged bleeding time in some cases due to:

- Thrombocytopenia

- Impaired platelet function

- Nutritional vitamin K deficiency (rare)

- PT/aPTT usually normal unless severe malnutrition or liver dysfunction

Mechanisms Driving Hematologic Changes:

| Mechanism | Effect |

|---|---|

| Malnutrition/starvation | Deficient substrates for hematopoiesis (iron, folate, B12, protein) |

| Hormonal dysregulation | Hypogonadism, low IGF-1 → impaired marrow stimulation |

| Marrow hypoplasia | Reduced hematopoietic cell mass |

| Cytokine imbalance | May suppress erythropoiesis or alter immune function |

Key lab findings:

| Test | Typical Result in AN |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | Low-normal or mild anemia |

| MCV | Normal or mildly low/high (depending on deficiencies) |

| Reticulocyte count | Low (hypoproliferative pattern) |

| WBC count | Often decreased, especially neutrophils |

| Platelet count | Normal or mildly low |

| Ferritin | May be normal or low, depending on inflammation and iron stores |

| Vitamin B12/folate | Low in restrictive or purging types |

| Bone marrow biopsy | Hypocellular, possibly gelatinous transformation |

Why are nutritional deficiencies (Fe, B12, folate) not more common in anorexia nervosa?

- Chronic adaptation and nutrient conservation:

- The body adapts to prolonged undernutrition by:

- Reducing metabolic rate

- Prioritizing essential nutrient use

- Recycling and conserving key vitamins and cofactors

- This allows many nutrient levels to stay within or near normal ranges, at least for moderate durations of illness.

- The body adapts to prolonged undernutrition by:

- Selective (not total) restriction:

- Many individuals with AN do eat small amounts regularly.

- Diets may be limited in calories but not devoid of all nutrients:

- For example, some maintain intake of fruits or fortified cereals (source of folate, B12).

- Pescatarians or vegetarians may still get iron or omega-3s.

- This prevents frank deficiencies of many vitamins or minerals.

- Slow depletion of stores:

- Several nutrients have large body stores or efficient recycling:

- Vitamin B12: stored in the liver, lasts 2–5 years

- Folate: smaller stores, but deficiency still takes weeks to months

- Iron: ferritin stores can last months

- Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K): stored in adipose and liver

- Because AN typically develops gradually, overt deficiencies may not be obvious until disease is advanced.

- Several nutrients have large body stores or efficient recycling:

- Subclinical deficiencies are more common than overt ones:

- Patients with AN may have biochemical or functional deficiencies without classic symptoms:

- Example: low-normal serum zinc or vitamin D levels without clinical signs

- Subtle issues like fatigue, poor wound healing, or mood changes may not be clearly attributed to nutrient deficiency.

- Patients with AN may have biochemical or functional deficiencies without classic symptoms:

- Normal lab tests can be misleading:

- Serum levels may remain “normal” even when tissue levels are depleted:

- For example:

- Serum B12 may appear normal even in early deficiency

- Albumin is often normal despite profound malnutrition (due to slow turnover)

- For example:

- Thus, overt deficiencies may be underrecognized unless specifically tested for or clinically severe.

- Serum levels may remain “normal” even when tissue levels are depleted:

Clinical Implications:

- Hematologic abnormalities in AN are reversible with nutritional rehabilitation.

- Pancytopenia and gelatinous marrow transformation are poor prognostic signs indicating severe and prolonged malnutrition.

- In unexplained pancytopenia in a young patient, AN should be on the differential, especially when associated with low BMI or psychiatric history.

Major Hematological Changes Observed in Hunger Strikers

Studies of hunger strikes and prolonged starvation in humans provide direct insights into the hematological changes that occur. The hematological manifestations found in hunger strikers are largely due to protein-energy malnutrition, much as in severe anorexia, but with some distinct features based on duration, degree, and the specific metabolic context of fasting or near-total starvation.

- Leukopenia:

- The most common hematologic abnormality, seen in over 60% of hunger strikers in some series.

- Both the total white blood cell count and specifically neutrophils often fall, though lymphocyte percentages may appear elevated due to relative shifts, not increased production.

- Hunger strikers show a significant drop (up to -24% in total WBC, -36% in neutrophils) by around 15 days of complete fasting, and lows may persist for weeks after refeeding.

- Thrombocytopenia:

- Platelet counts may decrease, especially with longer or more severe fasting. The drop is usually mild to moderate and predominantly reversible with nutritional rehabilitation.

- Anemia:

- Anemia in hunger strikers is less common in the early or moderate stages but can develop with longer starvation; severe anemia is uncommon unless the fast is prolonged and accompanied by micronutrient deficiencies.

- It is most often normocytic, normochromic, and related to bone marrow hypoplasia due to undernutrition, echoing findings in anorexia.

- Hemoglobin levels can also fall due to concurrent deficiencies of iron, folate, or B12 if refeeding is not managed.

- Red blood cell counts may increase slightly initially due to hemoconcentration but tend to fall later if malnutrition progresses.

- Coagulation Changes:

- Fasting is associated with a mild increase in coagulation times (INR and PTT increase), reflecting decreased synthesis of clotting proteins and vitamin K–dependent factors as fasting continues.

- The magnitude of change is greater with longer fasting.

- Bone Marrow Findings:

- Prolonged starvation can cause bone marrow atrophy (hypocellularity).

- Gelatinous transformation (replacement of normal marrow cells with fat and mucopolysaccharides) has been reported in both hunger strikers and individuals with severe eating disorders.

- Micronutrient Deficiencies:

In summary, hunger strike leads to a characteristic pattern of reversible cytopenias: primarily leukopenia (often severe), mild thrombocytopenia, and (if prolonged) normocytic anemia, along with marked micronutrient deficiencies, especially thiamine and folate, and bone marrow atrophy. These findings are highly relevant for clinical management, as close monitoring and timely nutritional/medical support are essential for preventing serious morbidity and mortality.

Primary Data

1) Sabel et al. Hematological abnormalities in severe anorexia nervosa. Ann Hematol. 2013 May;92(5):605-13.

- Retrospectively analysis of 53 men and women with severe anorexia nervosa.

- Predominantly female (89 %), with a median age of 28 years (range 17–65)

- Hospitalized for a median duration of 15 days

- 83 % of patients were anemic (hematocrit <37 %), with only 3 (6 %) having iron deficiency

- 79 % were leukopenic (WBC<4.5 k/μL)

- 29 % were neutropenic (ANC<1.0 k/μL)

- 25 % were thrombocytopenic (platelets<150 k/μL)

- 17 % of patients developed thrombocytosis (platelets>400 k/μL)

2) De Filippo E et al. Hematological complications in anorexia nervosa. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Nov;70(11):1305-1308.

- Retrospective study on the prevalence of these disorders in a large cohort of 318 female outpatients with AN

- 16.7% of patients had anemia, 7.9% neutropenia and 8.9% thrombocytopenia.

- These abnormalities were strictly related to the duration of illness

3) Guinhut M et al. Extremely severe anorexia nervosa: Hospital course of 354 adult patients in a clinical nutrition-eating disorders-unit. Clin Nutr. 2021 Apr;40(4):1954-1965

- 354 severely malnourished AN inpatients

- 339 patients were female and mean age was 28.7 ± 10.7 years old

- Duration of AN was 9.5 ± 9 years, 173 (48.9%) patients had a restricting AN subtype

- Anemia in 79% of cases – 20 patients required blood transfusion because of severe and poorly tolerated anemia

- Neutropenia in 53.9% of cases (neutrophil count<2000)

- Lymphocytopenia in 59% of cases (lymphocyte count<1500)

- Thrombocytopenia in 21% of cases (platelet level<150000)

- Bone marrow aspiration was performed in 24 patients (6.8%) because of persistent pancytopenia despite improvement of nutritional status; result was normal in 1 patient. A gelatinous bone marrow transformation (GBMT) was present in 23patients.

3) Gordon D et al. Security Hunger-Strike Prisoners in the Emergency Department: Physiological and Laboratory Findings. J Emerg Med. 2018 Aug;55(2):185-191.

- Retrospective study of 50 hunger-strike prisoners who were referred for evaluation to the ED after a longstanding fast.

- Results:

- Mean of 38 (28-44) days of a hunger strike

- Mean weight loss percentage was 18.5%

- most patients were bradycardic (25/40 [62.5%]), and some hypothermic (16/50, [32%])

- Leukopenia was the most common hematologic manifestation (31/50 [62%])

- Pancytopenia was observed in 4/50 (8%) patients

- Prolonged INR was observed in 12/29 (41.3%) patients

- Authors: “We assume that anemia is more common than the observed rate, considering the presence of dehydration and hemoconcentration in most patients.”

4) Dai et al. Analysis of physiological and biochemical changes and metabolic shifts during 21-Day fasting hypometabolism. Sci Rep. 2024 Nov 18;14(1):28550.

- Thirteen volunteers were selected through public recruitment to undergo a 21-day complet.e fasting experiment.

- Most of the blood cell count items did not change drastically during the CF period.

- Notable changes were observed in the white blood cell system including:

- White blood cell count (WBC) – decreased on the CF15 by -24.28%

- Neutrophils count (NEUT) – decreased by -36.31%

- Hemoglobin concentration (HGB) showed a significant increase on the CF5 and CF10 but then began to regain.

- The platelet count (PLT) and plateletcrit (PCT) did not change.

5) Wilhelmi de Toledo et al. Safety, health improvement and well-being during a 4 to 21-day fasting period in an observational study including 1422 subjects. PLoS One. 2019 Jan 2;14(1):e0209353.

- 1422 subjects participated in a fasting program consisting of fasting periods of between 4 and 21 days.

- Results:

- Leucocytes decreased significantly in all groups (fasting intervention: p<0.001).

- Stronger reduction in the groups who fasted longer (fasting duration group-by-fasting intervention: p<0.001).

- Erythrocytes showed an increase (fasting intervention: p<0.001) of an average of 0.06 x106/μl in all groups and steadied at around 4.82×106/μl.

- Hemoglobin showed also an increase (fasting intervention: p<0.001) of about 0.1 mmol/L that was independent of the fasting length.

- Thrombocytes showed a significant reduction (fasting intervention: p<0.001) during fasting by a mean of 6.6±0.7×103/μl, with gender difference (fasting intervention-by-sex: p<0.001) and influence of the fasting length (fasting duration group-by-fasting intervention: p<0.001).

- INR and PTT increased (fasting intervention: each p<0.001)