I posted a poll asking whether one would treat pregnancy-associated and/or incidentally discovered ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) with anticoagulation.

Bottom line

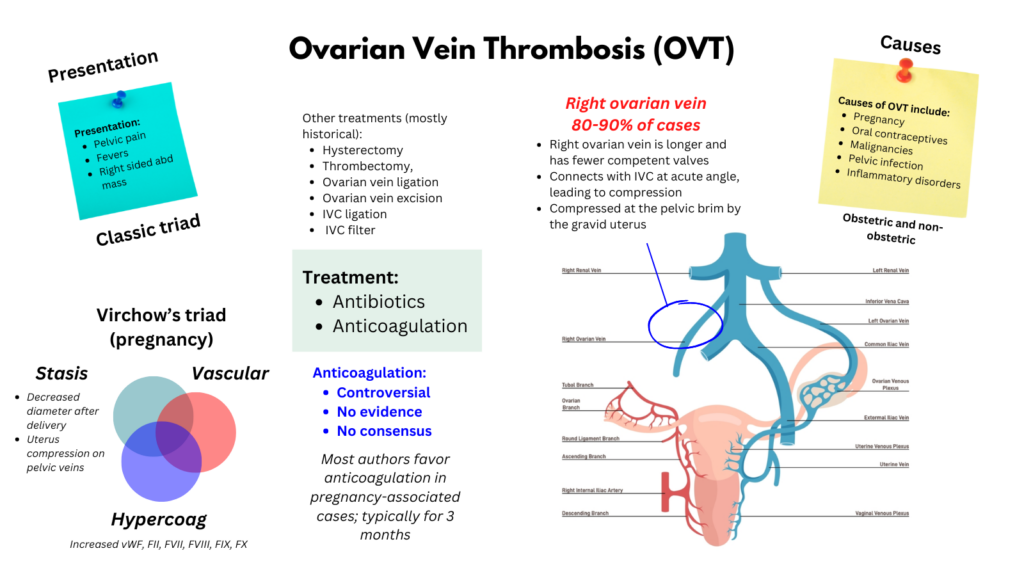

There is no “right” answer! Ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) is rare. While case series have been published, there are virtually no controlled trials that inform management. OVT that is associated with the postpartum period or pelvic infection/inflammation typically presents with a septic thrombophlebitis picture (triad of pain, fever, and abdominal mass). The consensus is to treat postpartum cases with antibiotics and therapeutic anticoagulation, with some authors limiting anticoagulation to those patients who are symptomatic. For those who develop OVT outside the setting of pregnancy, including incidentally discovered OVT, expert opinion is all over the map with some advocating for no anticoagulation and others arguing for longer (e.g., 6 months) anticoagulation.

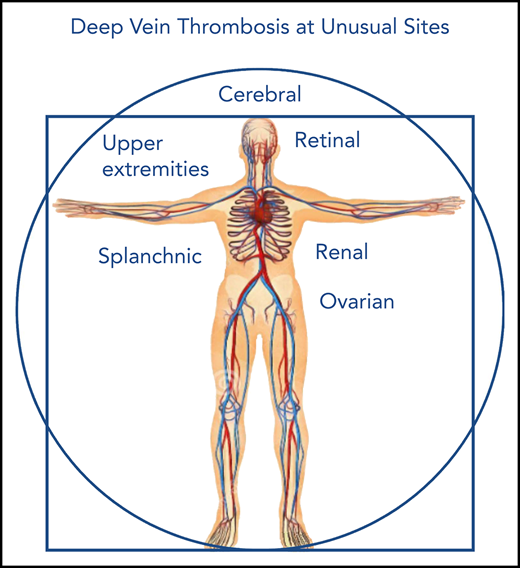

Note: Keep in mind that while other “unusual site” venous thrombi, specifically those within the splanchnic bed, are not at risk of embolizing to the lung (emboli are filtered by the liver sinusoids), the ovarian veins drain into the inferior vena cava (the right vein directly connects, the left vein connects via the renal vein), so there is a real chance of an ovarian vein thrombus embolizing to the lung.

Introduction

- Ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) is a type of unusual-site venous thrombus involving the female gonadal veins.1

- Most often seen in the immediate postpartum period (typically within 4 weeks postpartum), but also occurs in the nonobstetrical setting of malignancy, abdominal and pelvic surgery, pelvic inflammatory disease, and inflammatory bowel disease and hypercoagulable states.2 3

- Ovarian vein thrombosis is an uncommon event, complicating 0.05% to 0.18% of pregnancies and affecting the right vein in up to 90% of cases.

- The term septic pelvic thrombophlebitis is often used interchangeably with OVT in the literature, though it most often refers to OVT in pelvic inflammatory disease or in the postpartum setting where there is concern for presence of endometriosis and secondary infection of the vein wall and thrombus.4

History

- Septic pelvic thrombophlebitis was first described by von Recklinghausen at the end of the 19th century:

- All cases presented with ovarian vein thrombosis and pelvic infection.

- von Recklinhausen proposed surgical excision as the preferred treatment.

- Resulted in a 50% rate of mortality.

- In 1909, Williams reported a 50% mortality rate among 56 women undergoing excision of thrombosed pelvic veins complicating “puerperal pyemia.”5

- In 1951, Collins at al published a great series of what he called suppurative pelvic thrombophlebitis for which they advocated the practice of ligature of the inferior vena and ovarian veins as the most effective treatment.

- Right-sided OVT in context of other clots described in N Eng J Med CPC in 1951.

- Case report of isolated OVT described by Austin in 1956.

- In the mid-1960s, the combination antibiotic and heparin therapy became the preferred treatment plan. It was widely held that when heparin administration was followed by defervescence this was diagnostic of septic phlebitis.6

Epidemiology

- Ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) is about 60 times less common than lower limb deep vein thrombosis (DVT).7

- Higher incidence in recent years due to the widespread use of radiological imaging and its technical improvements.8

- Pregnancy-associated OVT (POVT):9

- Usually diagnosed in women in their early thirties.

- More common after caesarean delivery than vaginal delivery.

- Complicates approximately 0.01 to 0.18% of pregnancies (600 to 1 per 2,000 pregnancies), up to 2% of Caesarean sections.1011

- In a prospective study performed between 2004–2007, the incidence of OVT was:

- 0.02% after vaginal delivery

- 0.1% after caesarean section

- 0.67% when caesarean delivery was performed for a twin pregnancy.

- In one study, 53% of women with POVT had evidence of infection, including:

- Amnionitis

- Bilateral pneumonia

- Urinary tract infection

- Extensive wound infection

- 80–90% of the cases involve the right ovarian vein.12

- Non-pregnancy associated OVT:13

- Mean age ranges from 40 to 60 years.

- Postoperative OVT is rare, with prior investigations reporting a crude incidence of 0.10%, 0.13%, and 0.24% in vaginal, laparoscopic, and abdominal approaches, respectively.14

- Cohorts of patients with gynecological malignancies undergoing cancer surgery:15

- In a cohort of 50 women with either cervical, ovarian or endometrial cancer, undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, 40 patients (80%) had an incidental finding of unilateral OVT at follow-up CT scan.

- In a cohort of 159 patients undergoing a routine CT scan 12 weeks post-operatively after debulking surgery for ovarian cancer and found incidental findings of OVT in 41 (25.8%) of them

- In a cohort of 417 patients after gynecological cancer surgery including bilateral adnexectomy; 55 (13.2%) of them were diagnosed with incidental OVT within 6 months,

- Due to the anatomical difference in venous drainage, the right ovarian vein is more frequently involved (70–80% of cases); occasionally, the thrombosis can be bilateral (around 10% of cases). This disparity is more pronounced in pregnancy-associated OVT compared with non-pregnancy-associated OVT.16

Pathophysiology

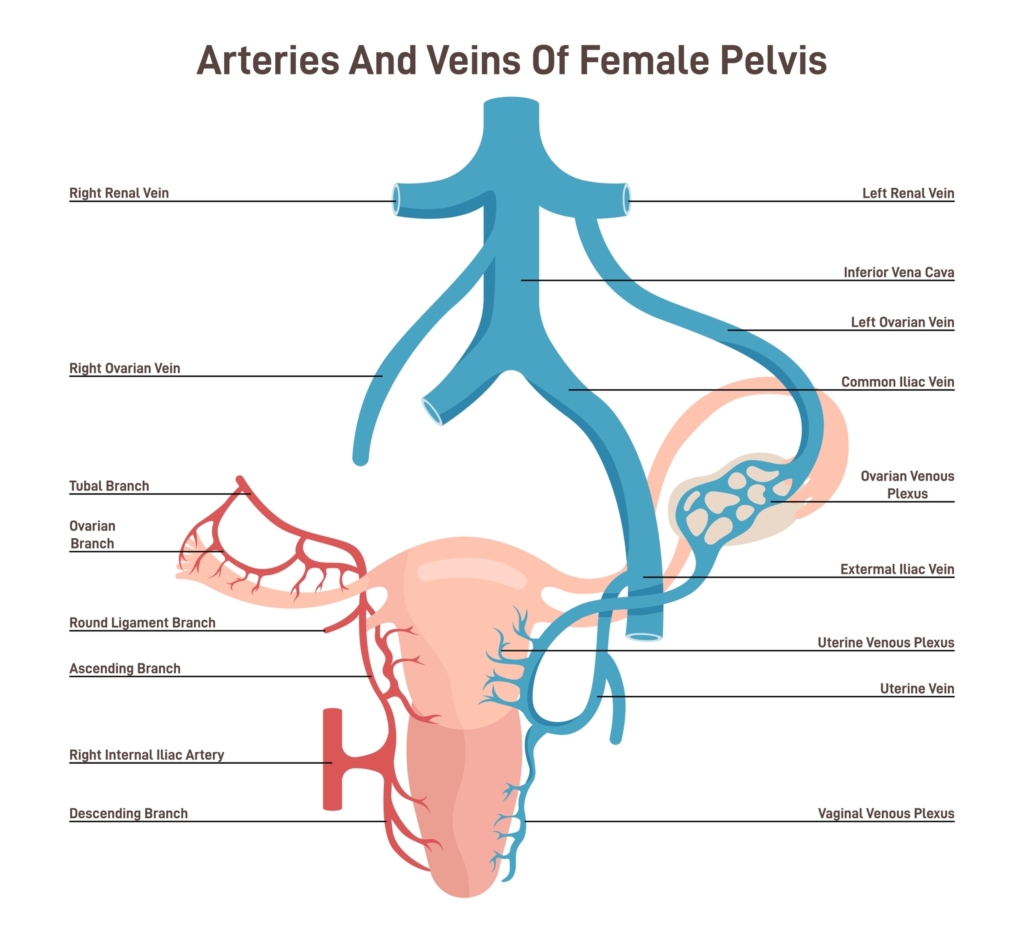

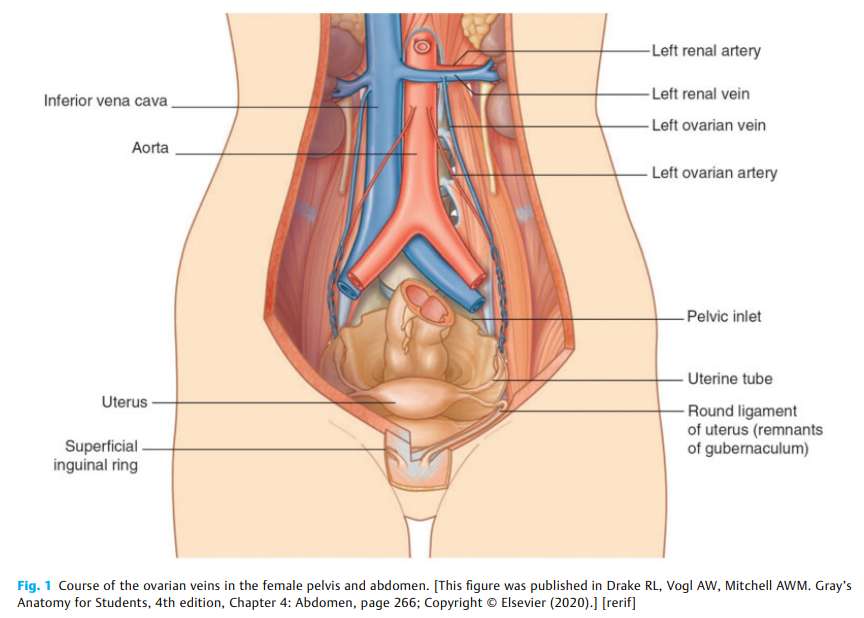

- Normal anatomy:17

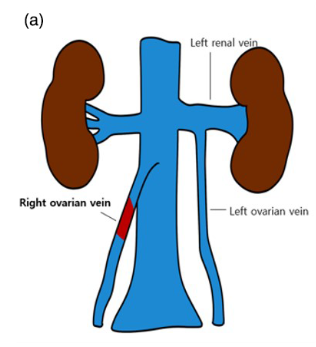

- Anatomically, the ovarian vein represents a portion of the deep venous system with a direct connection to the inferior vena cava on the right and the renal vein on the left.18

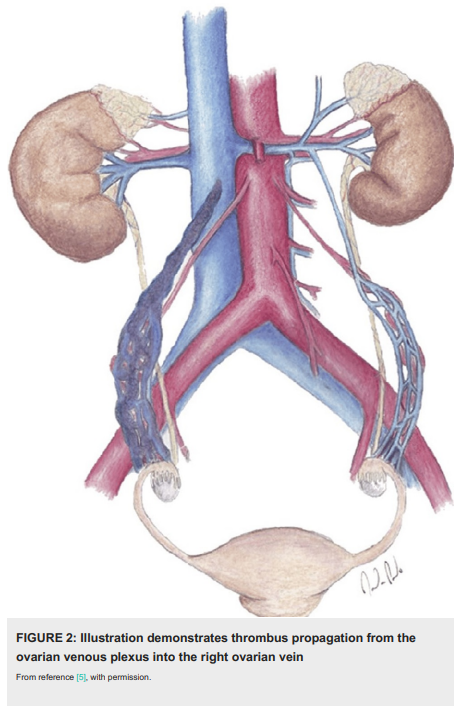

- The ovarian veins originate in the pelvis from the ovarian venous plexus, which in turn communicates with the uterine venous plexus in the broad ligament of the uterus.

- They ascend into the abdominal cavity anterior to the psoas muscle and cross the ureters at the level of the third/fourth lumbar vertebra.

- The right ovarian vein is a direct tributary of the inferior vena cava; it drains at an acute angle on the anterolateral aspect of the inferior vena cava (IVC) at the L2 level.

- The left ovarian vein drains into the left renal vein with a straight angle (right angle).

plexus, afterwards, the ovarian vein passes superiorly along and anterior to the psoas muscle. The drainage

of the right ovarian vein is commonly to the inferior vena cava (IVC), while the left ovarian vein drains into

the left renal vein. Hamostaseologie. 2021 Aug;41(4):257-266.

- Causes:19

- Ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) is associated with:

- Pregnancy:20

- Termed postpartum OVT (POVT).

- Typically occurs on the right side.

- Appears more often after a caesarean section compared with vaginal delivery.

- POVT is a septic complication occurring:21

- During the postpartum (usually presents within 10 days postpartum) or postoperative period of high-risk deliveries, caesarean section, and abortion.

- In the prepartum period, after abortion, and ruptured ectopic pregnancy, and in cases of hydatidiform mole.

- Oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy

- Malignancies:22

- Most commonly genitourinary cancers (such as ovarian or uterine tumors) followed by gastrointestinal cancers, including pancreatic and hepatic malignancies.

- Breast, lung, or hematologic cancers are less commonly reported.

- In some studies, cancer reported to be the most common risk factor for OVT.23

- Recent surgery

- Pelvic infections:

- Endometritis

- Chorioamnionitis

- Inflammatory disorders

- Inflammatory bowel diseases

- Appendicitis

- Diverticulitis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Pregnancy:20

- Overall, the most common risk factors are:

- Malignancy (11–60%)

- Pregnancy/puerperium (9–61%)

- Abdominal surgery (6–70%)

- Cohort studies:

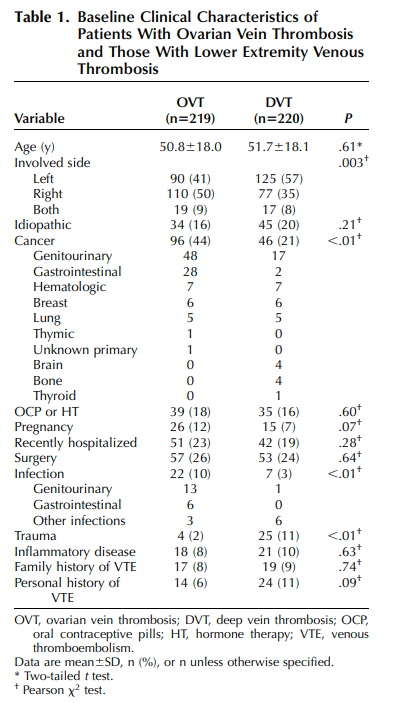

- Cohort of 219 patients with OVT (41% left, 40% right, 9% both sides):

- 44% had underlying cancer, mostly genitourinary and gastrointestinal malignancies.

- 18% were on OCP.

- 12% were pregnant.

- 26% underwent recent surgery.

- Infection in 10%, mostly genitourinary and GI.

- 16% were idiopathic

- Cohort of 40 patients with OVT:

- 34% associated with malignancies.

- 23% with PID.

- 20% with pelvic surgeries.

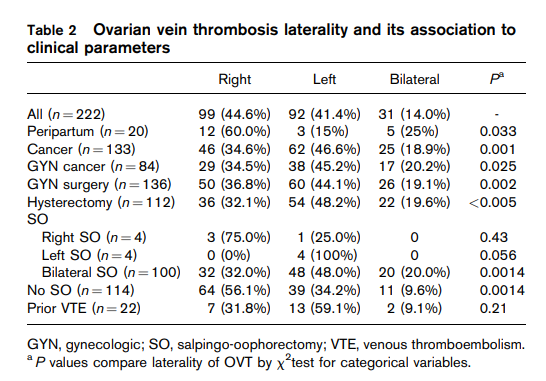

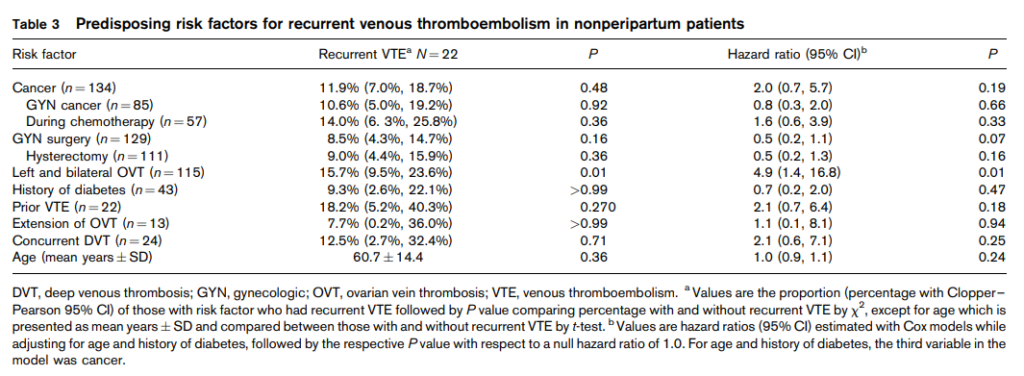

- Cohort of 223 patient with OVT:

- 20 patients were peripartum.

- 134 patients had cancer (85 gynecologic).

- 137 patients had prior gynecologic surgery.

- Cohort of 74 women diagnosed with OVT:

- Sixty (81.1%) cases were pregnancy related.

- 14 (18.9%) were non-pregnancy related.

- Cohort of 50 patients with OVT (60% of OVT were within the right gonadal vein, 14% were bilateral, and 24% were in the left gonadal vein):

- One subject had a diagnosis of sickle cell trait.

- One patient had anticardiolipin antibody.

- 11 patients had an active malignancy.

- 9 patients were peri- or postpartum.

- 11 patients had surgery within 3 months of diagnosis.

- 3 patients had remote surgery.

- 4 patients had an active infection at time of diagnosis.

- Cohort of 26 patients were diagnosed with OVT (thrombosis occurred in left ovarian vein in 50 percent (13/26), in the right ovarian vein in 42 percent (11/26), and bilaterally in 8 percent (2/26) of patients):

- Malignancy (27 percent, 7/26)

- Non-pregnancy related pelvic surgery (23 percent, 6/26)

- Postpartum state accounted for only 12 percent (3/26) of the cases.

- Cohort of 219 patients with OVT (41% left, 40% right, 9% both sides):

- Ovarian vein thrombosis (OVT) is associated with:

- Pathogenesis:

- Disturbance in Virchow’s triad:24

- Pregnancy-associated OVT:

- Hypercoagulability:

- Increased levels of procoagulant factors:

- Fibrinogen

- Factors VII, VIII, and X

- von Willebrand factor

- Change in the levels of natural anticoagulants:

- Reduced protein S activity

- Increased activated protein C resistance)

- Reduced fibrinolysis

- Increased levels of procoagulant factors:

- Venous stasis:25

- Uterus compression on pelvic veins.26

- Ovarian vein diameter increases threefold in pregnancy, and after delivery blood flow in the veins decreases, leading to stasis.

- The absence of ovarian vein valves has been reported in 6 to 15% of women.

- Endothelial injury can occur during childbirth (both vaginal delivery and caesarean section).

- Hypercoagulability:

- Cancer-associated OVT:

- Hypercoagulability:

- Release of procoagulant tissue factor or microparticles by tumor cells.

- Acquired protein C resistance.

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation.

- Venous stasis can be due to:

- Immobilization

- Compression of blood vessels by locally advanced tumors.

- Endothelial injury can result from vascular invasion by the growing tumor.

- Hypercoagulability:

- Pregnancy-associated OVT:

- Several anatomic and physiologic factors may explain the predominance of right OVT, especially in in pregnancy-related OVT:27

- Compared with the left ovarian vein, the right ovarian vein:

- Is longer and has fewer competent valves.28

- Connects directly to the inferior vena cava at an acute angle, further increasing its vulnerability to compression.

- Has anterograde blood flow into the inferior vena cava (which can favor thrombus extension) vs. left ovarian vein where retrograde flow has been reported into the internal iliac vein (which can predispose to the formation of ovarian varicoceles and pelvic congestion syndrome).29

- Is frequently compressed at the pelvic brim by the physiological dextrorotation of the uterus during pregnancy (the uterus rotates to the right).

- Because the left ovarian vein empties into the left renal vein, any pathology affecting the left kidney (for example, infection, nephropathy, cancer, trauma) will preferentially affect the left ovarian vein.30

- Compared with the left ovarian vein, the right ovarian vein:

- It has been suggested that up to 50% of patients who are found to have OVT have a prothrombotic predisposition, such as antiphospholipid syndrome, factor V Leiden mutation, or protein S deficiency31

- Disturbance in Virchow’s triad:24

Clinical Presentation

- The presentation of OVT is pernicious, often presenting as a fever unresponsive to antibiotics.

- Postpartum OVT:

- Occurs with a peak around 2 to 6 days after delivery or miscarriage/abortion.

- Symptoms generally occur in the first 4 weeks postpartum.

- Arises within 10 days in 90% of women.

- The classic presentation of OVT is the triad of:

- Pelvic pain (66%):32

- Lower quadrant abdominal pain, usually on the side of the thrombosed vein.

- The pain may radiate to the flank, upper abdomen, or the groin.

- Acute abdominal tenderness can be noticed on physical examination.

- Fever (80%):

- Usually spiking

- Associated with chills

- Right-sided abdominal mass (46%):

- Palpable cord-like, ropelike and/or sausage-shaped abdominal mass.

- Extends from the ovary to the paracolic gutter and corresponding to the thrombosed ovarian vein.

- Pelvic pain (66%):32

- Other findings may include:3334

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Tachypnea

- Lower quadrant or flank pain

- Nausea, vomiting

- Guarding

- Anorexia

- Malaise

- Ileus

- Pyuria

- Nonspecific back pain

- Leukocytosis is common.

- Although uterine infection is present or suspected in the majority of cases before or at the onset of symptoms of OV; however, blood cultures are positive in rare cases.3536

- Cohort of 74 women diagnosed with OVT:

- 89.2% had acute presentation.

- 6.8% had chronic course.

- 4.1% were asymptomatic.

- Symptoms included:

- Lower abdominal pain (78.4%)

- Constitutional symptoms such as:

- Nausea, vomiting, or anorexia (14.9%)

- Malaise (8.1%)

- Fever was present in 52.7% of patients.

- On examination, abdominal tenderness was noted in 57 (77%).

- Palpable abdominal mass was found in one patient (1.4%).

- Compared to non-pregnancy related cases, patients with pregnancy-related OVT tended to present with fever (P = 0.02) and acute symptomatology (acute presentation: 93.3% vs. 71.4%, chronic: 3.3% vs. 21.4%, asymptomatic: 3.3% vs. 7.1%, P = 0.04). Symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and malaise were more common among non-pregnancy related cases (P = 0.004 and P = 0.08, respectively).

Diagnosis

- Laparotomy:37

- In the past, laparotomy was used as a diagnostic tool for OVT

- Still considered the gold standard.

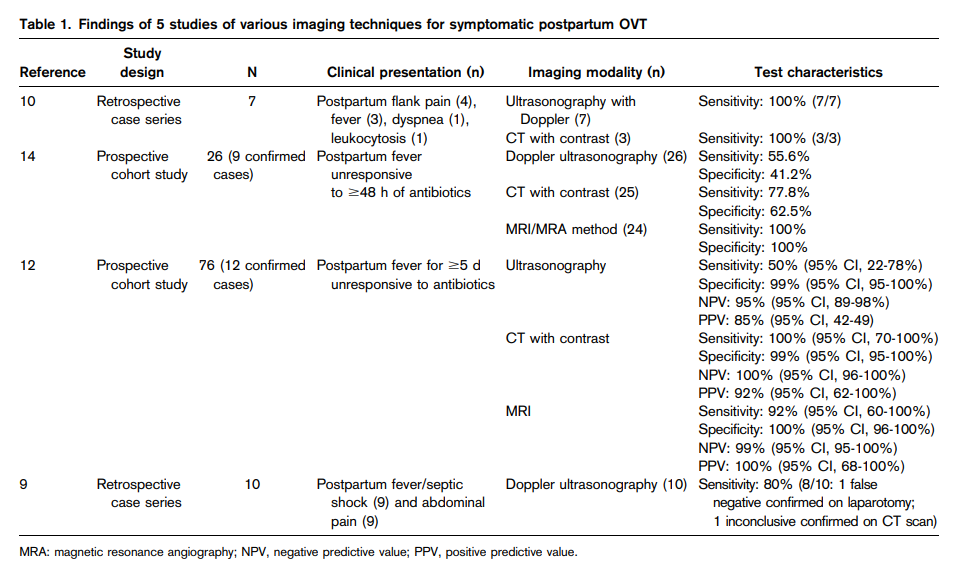

- Diagnosis of OVT can be obtained using ultrasound (US) Doppler, CT, or MR. However, there is no definite consensus regarding the gold standard test, as only a few studies specifically evaluated sensitivity and specificity:

- US Doppler:38efn_note]PMID 29296754[/efn_note]

- Usually the first-line imaging

- Advantages:

- Safety

- Low cost

- Wide availability

- Free of radiation

- Does not require contrast

- Can also be performed at the patient’s bedside with the use of portable instruments.

- Disadvantages:

- Operator-dependent

- Imaging and can often be inconclusive, due to the presence of overlying bowel gas, abdominal meteorism or obesity which interfere with the visualization of the ovarian veins.

- Findings:

- Thrombosis of the ovarian vein at US appears as an anechoic/hypoechoic mass located superiorly to the ovary and anteriorly to the psoas muscle.

- The thrombus can sometimes be seen as an intraluminal mass extending from the ovarian veins into the inferior vena cava or the renal vein.

- US Doppler shows decreased or absent flow in the ovarian vein, depending on whether the occlusion is partial or complete.

- Sensitivity of US has been reported in the range 50 to 100% and specificity in the range 41 to 99%.

- CT scan (contrast-enhanced CT or CT venography):39efn_note]PMID 29296754[/efn_note]

- Can better identify the presence and the extension of the thrombosis and is nowadays the reference imaging.

- However, CT involves the use of ionizing radiations and iodinated contrast medium, and possible contraindications include pregnancy, renal insufficiency, and previous contrast allergy.

- Typical findings of OVT on contrast-enhanced CT comprise dilation of the ovarian vein, enhancement of the vascular wall, and the presence of a low-density intraluminal filling defect (the Zerhouni criteria).

- The superior extension of the thrombus might be difficult to define precisely with CT scan due to the mixing effect between enhanced and nonenhanced blood at the level of the renal veins, which can give a false-positive image of filling defect in the inferior vena cava.

- Sensitivity of CT has been reported to be 77 to 100% and specificity to be 62 to 99%.

- Magnetic resonance (MR):[efn_note]PMID 33348392[/efn_note]efn_note]PMID 29296754[/efn_note]

- Does not use ionizing radiation or iodinated contrast medium

- However, disadvantages include longer execution time, higher costs, and nonavailability for immediate use.

- Unenhanced MR can allow the direct visualization of the thrombus.

- Sensitivity of MR has been reported to be 92 to 100% and specificity approximately 100%; thus, MR is indicated when CT scan is inconclusive and the suspicion of OVT persists.

- US Doppler:38efn_note]PMID 29296754[/efn_note]

- Bannow and Skeith:

- Pelvic MRI has the highest sensitivity and specificity for suspected postpartum OVT when compared with CT or ultrasonography with Doppler.

- However, CT or ultrasonography may be more practical to use in many cases.

- Recommendations:

- 1. The choice of the initial imaging technique for suspected OVT may vary based on test availability and patient characteristics. Pelvic MRI appears to have the highest sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of OVT (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation [grade] 2C).

- 2. If ultrasonography is used to diagnose OVT, we suggest the addition of Doppler imaging to improve test accuracy (grade 2C).

- Canadian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Clinical Practice Guideline on Venous Thromboembolism and Antithrombotic Therapy in Pregnancy:

- Computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (with or without angiography) are the definitive imaging modalities to rule out ovarian vein thrombosis. (II-2A)

Differential Diagnosis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Endometritis

- Pyelonephritis

- Nephrolithiasis

- Acute appendicitis

- Ovarian torsion

- Broad ligament hematoma

- Adnexal abscess

- Sepsis

Treatment

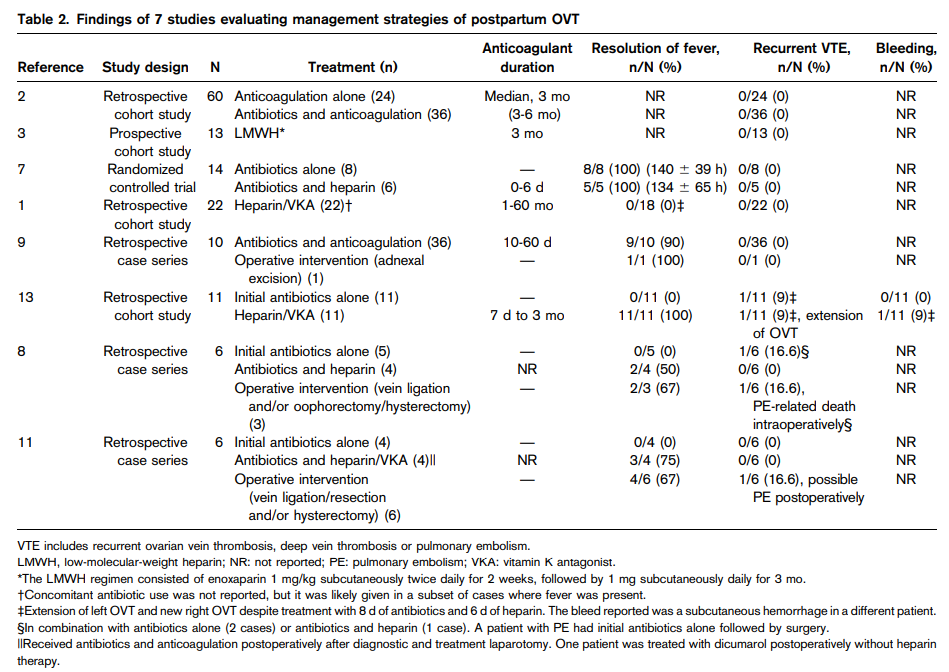

- There are currently no treatment guidelines for OVT.

- Given the relative rarity of ovarian vein thrombosis, it is unlikely that a randomized controlled trial will ever be carried out.

- Historically:40

- Surgical excision of the thrombosed vein was the treatment of choice until the 1950s.

- Ligature of the inferior vena cava and ovarian veins was advocated in the 1950s.

- Heparin anticoagulation and antibiotics gained widespread acceptance in the 1960s.

- Other treatments have included:41

- Hysterectomy

- Thrombectomy

- Ovarian vein excision

- IVC ligation

- IVC filter placement

- The following is an example of a treatment regimen for OVT:42

- 7 to 10 days of anticoagulation with IV heparin bridged to warfarin; up to 3 months of warfarin has been recommended if thrombus extends into renal veins or the IVC; however, there is lack of consensus in literature regarding need to anticoagulation, optimal anticoagulant treatment regimen and duration.

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics:

- Antibiotics are used as empiric treatment for endometritis in the postpartum setting when OVT presents with fever and abdominal pain.43

- No consensus in literature on optimal dose and duration; usually provided for 48-72 hours, but may be continued for 7-10 days or until patient is afebrile for 24-72 hours.

- OVT can resolve spontaneously; the need for treatment, particularly anticoagulation, has been debated. 44

- Studies not supporting use of anticoagulation:

- Cohort of 15 patients with POVT:

- Of 14 women randomly assigned to therapy, 8 were assigned to receive continued antimicrobial therapy without the addition of heparin and the other 6 were assigned to receive heparin therapy in addition to the antimicrobial agents.

- According to an intent-to-treat analysis there was no significant difference between the responses of women with pelvic infection who were and were not given heparin therapy.45

- None of the subjects continued anticoagulation upon discharge, and there were no apparent complications at 3 months of follow-up.

- Hypercoagulability and thrombus extension were not discussed by the authors of this study.

- Authors’ conclusions: “Women given heparin in addition to antimicrobial therapy for septic thrombophlebitis did not have better outcomes than did those for whom antimicrobial therapy alone was continued. These results also do not support the common empiric practice of heparin treatment for women with persistent postpartum infection.”

- Cohort of 50 patients with OVT:

- Treatment:

- 12 subjects had no treatment.

- 2 had IVC filters placed.

- 3 were treated with antibiotics and anticoagulation.

- 30 were given anticoagulation alone.

- 1 was given aspirin alone.

- Average age at diagnosis was 43.4 years.

- 80% had signs or symptoms of OVT on presentation; 18% idiopathic

- 60% right ovarian vein.

- 14% were diagnosed with thrombi into other locations at the time of OVT.

- Average length of follow-up was 23.7 months.

- Average length of anticoagulation was 13.2 weeks.

- Ten patients had imaging showing resolution of OVT after anticoagulation, whereas 2 who received no anticoagulation had radiographically confirmed resolution of OVT.

- Five patients treated with therapeutic anticoagulation exhibited persistent OVT following treatment, whereas 4 who did not receive anticoagulation had persistent OVT on follow-up imaging.

- Symptomatic recurrence or bleeding was not seen in any subjects.

- There was no statistically significant correlation found between treatment and no treatment in terms of overall outcomes for patients diagnosed with OVT.

- Authors’ conclusions: “Based on our findings, unless an OVT is symptomatic, septic in nature, or associated with another deep venous thrombosis (DVT) requiring treatment, an incidentally detected OVT does not necessarily warrant anticoagulation therapy.”

- Treatment:

- Cohort of 50 women with gynecologic malignancies who were 3 to 20 months postoperative from total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy:

- Thirty of these patients had ovarian cancer (60%), 15 (30%) had cervical cancer, and five (10%) had endometrial cancer.

- 80% of the patients were found to have incidental, occlusive, unilateral OVT.

- No surrounding stranding to suggest phlebitis was seen in any of the patients.

- Twenty patients had repeat CT scans at 3 to 24 months that showed unchanged OVT.

- Anticoagulants were not given to these patients.

- These subjects had CT scans every 3 months over a 2-year period and no apparent complications from OVT were seen.

- Authors’ conclusions: Patients who had no radiologic evidence of phlebitis and were without symptoms of PE did not require treatment.

- Cohort of 417 patients with endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer (including borderline malignant tumors, fallopian tube cancer, and peritoneal cancer), and cervical cancer who underwent surgery including bilateral adnexectomy:

- 610 patients underwent surgery, including bilateral adnexectomy for gynecological malignancies.

- Of these, 417 patients who underwent contrast-enhanced CT within 6 months after surgery were enrolled in this study

- OVT occurred in 55 (13.2%) of 417 patients.

- All 55 cases were asymptomatic.

- Of the 417 patients enrolled, 387 (92.8%) received some form of prophylactic anticoagulant therapy in the perioperative period. There was no difference in the frequency of OVT with or without prophylactic anticoagulant therapy (13.4% vs. 10.0%; p = .80).

- Only 6 patients (10.9%) received anticoagulant therapy as a treatment for thrombosis.

- In the group that did not receive anticoagulant therapy, 4 patients showed enlargement of the thrombus in the ovarian vein, which did not reach the IVC or renal veins in any case.

- OVT was resolved during the follow-up period in 42 cases (76.4%), and no difference was observed in the resolution rate with or without anticoagulant therapy (83.3% vs. 75.5%, respectively; p = .32). The median time to OVT resolution was 8 months in the treatment group and 16 months in the no-treatment group, with no significant difference between the groups (p = .81).

- VTE occurred within 1 year after surgery in only 1 case (1.8%) in the OVT group and in 10 cases (2.8%) in the no-OVT group. In addition, PE occurred within 1 year after surgery in 5 cases (1.4%) in the no-OVT group, but did not occur in the OVT group.

- No difference in the resolution rate of OVT was found between those who received anticoagulant therapy and those who did not, and none of the patients developed PE from OVT.

- Authors’ conclusions: “To the best of our knowledge, no study has reported that PE can occur as a result of OVT in cases where the ovarian vein is intercepted by adnexectomy. In this study, although most patients had not received anticoagulant therapy, the thrombus resolved spontaneously in 76.4% of patients, and no difference was found in the resolution rate with or without anticoagulant therapy. In addition, the thrombus did not progress to the renal vein or IVC, which leads to PE, in any case. Therefore, anticoagulant therapy is not needed for asymptomatic OVT after adnexectomy.”

- Cohort of 15 patients with POVT:

- Studies supporting use of anticoagulation:

- Cohort of 35 patients with OVT and 114 female patients with lower extremity venous thrombosis (DVT):

- The average length of anticoagulation with warfarin was 5.3 months in the OVT group and 6.9 months in the DVT group.

- During a mean follow-up period of 34.6 +/- 44.3 months, three patients suffered three recurrent venous thrombi (event rate: three per 100 patient years of follow-up). This recurrence rate was comparable to patients with lower extremity DVT (2.2 per 100 patient years).

- Recurrent thrombosis involved the contralateral ovarian vein, left renal vein, and inferior vena cava.

- All events within the OVT group occurred within the first 2 months of the initial thrombus.

- Authors’ conclusions: “In conclusion, venous thromboembolism recurrence rates are low and comparable to lower extremity DVT. Therefore, general treatment guidelines for lower extremity DVT may be applicable (3 months of anticoagulation if an underlying cause was identified, whereas a longer course might be considered if an OVT was idiopathic).”

- Cohort of 35 patients with OVT and 114 female patients with lower extremity venous thrombosis (DVT):

- Expert opinion:

- Klima and Snyder:

- “Given the conflicting and sparse data, at the present time, we believe the best treatment for postpartum ovarian vein thrombosis is antibiotics in combination with anticoagulation… considering the risk/benefit ratio of heparin or enoxaparin in a patient with a large propagating thrombus, it seems very reasonable to use anticoagulation in addition to antibiotics until better data are available.”

- “Most authors recommend continuing antibiotics for 48–72 hours and anticoagulation for at least 7–10 days after fever resolution. If extensive thrombus into renal veins or inferior vena cava is noted, 3 months of warfarin may be indicated.”

- Bannow and Skeith:

- Based on the current evidence and extrapolation from principles of treatment of other forms of VTE, anticoagulant therapy is indicated for patients with symptomatic postpartum OVT, and antibiotics should be used adjunctively when infection is suspected.

- Asymptomatic postpartum OVT is common in the general obstetrical population, and treatment may not be needed.

- Recommendations:

- For symptomatic postpartum OVT we suggest a short duration (3 months) of anticoagulation, with the addition of antibiotics in the cases of suspected infection (grade 2C).

- We suggest against use of an extended duration (>3 months) of anticoagulation (grade 2C) and emphasize the need for additional studies to determine the most appropriate duration of treatment.

- For asymptomatic postpartum OVT, we suggest against the use of anticoagulation unless there is evidence of thrombus extension or pulmonary embolism (grade 2C).

- Klima and Snyder:

- Expert opinion: (cont’d)

- Abbattista et al:

- On the basis of this evidence and extrapolating the duration of anticoagulant therapy from the ACCP guidelines on the treatment of LEDVT, 3 months are suggested for symptomatic postpartum OVT, with the addition of antibiotic therapy, if needed.

- Anticoagulant therapy is discouraged in asymptomatic postpartum-associated OVT with no evidence of thrombus extension or pulmonary embolism.

- Kodali et al:

- “Initiation and appropriate duration of anticoagulation are also a matter of debate. Some argue that incidentally found OVT related to surgery may not need anticoagulation unless complications are noted. A majority of experts believe rare thrombosis should be treated like lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The application of DVT guidelines is considered reasonable as outcomes are comparable. There are no definitive guidelines for duration of anticoagulation. Some case reports suggest repeating imaging after 40 or 60 days and stopping anticoagulation if the resolution of thrombus or calcification is noted on follow-up imaging.”

- Virmani et al:

- POVT is a potentially life-threatening condition, therefore, correct diagnosis and prompt treatment is important to avoid complication.

- OVT in the non-obstetrical setting may not require treatment and can be safely followed up with imaging.

- Rottenstreich et al:

- “Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal duration of anticoagulation therapy. Pregnancy-related OVT is characterized by a provoked nature and a high rate of resolution after short term treatment. In this study, treatment of three months duration of anticoagulation appeared to be safe, with no recurrences encountered during a median follow up of 40 months. The high rates of active infection found in our study support the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics during the acute phase.”

- “In non-pregnancy related cases… we suggest considering a longer duration of anticoagulation therapy, up to 6 months, especially in patients with thrombosis extension or positive thrombophilic evaluation.”

- Plastini et al:

- “Unless an OVT is symptomatic, septic in nature, or associated with another deep venous thrombosis (DVT) requiring treatment, an incidentally detected OVT does not necessarily warrant anticoagulation therapy.”

- UpToDate:

- “We suggest systemic anticoagulation [for septic pelvic thrombophlebitis] in addition to antibiotic therapy for the management of SPT. Anticoagulation is thought to prevent further thrombosis and reduce the spread of septic emboli”.

- “For patients who have radiographic evidence of extensive pelvic thromboses (e.g., thrombosis involving the ovarian vein, iliac veins, or vena cava) or septic emboli, we continue anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin or an oral anticoagulant for at least six weeks. Six weeks is likely adequate for pelvic vein thrombosis related to pregnancy or other transient processes. Anticoagulation for longer than six weeks may be appropriate for patients with embolic disease outside the pelvis or with more chronic pro-thrombotic risk factors (including factor V Leiden trait or hypercoagulability related to malignancy); we typically consult with a hematologist regarding the optimal duration.”

- Abbattista et al:

- Clinical Practice Guidelines:

- Canadian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Clinical Practice Guideline on Venous Thromboembolism and Antithrombotic Therapy in Pregnancy:

- Broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics should be initiated with the diagnosis of OVT and continued for at least 48 hours after defervescence and clinical improvement. (II-2A)

- A longer treatment course is required in the presence of septicemia or complicated infections. (III-C)

- Even though a small, randomized study (N = 14) did not report a difference in the resolution of the fever with antibiotics alone versus antibiotics plus UH concurrent anticoagulation is often recommended. We recommend anticoagulation for 1 to 3 months (III-C). There are no studies to guide the risk of recurrence of OVT and the need for thromboprophylaxis in subsequent pregnancies. The risk is likely low.

- British Society of Haematology Guidelines on the investigation and management of venous thrombosis at unusual sites:

- Post-partum ovarian vein thrombosis should be treated with conventional anticoagulation for 3–6 months as for other cases of post-partum VTE (1C).

- Incidentally identified ovarian vein thrombosis in patients who have undergone total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with retroperitoneal lymph node dissection does not require anticoagulation except in the rare patient with IVC extension or PE (2C).

- Canadian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Clinical Practice Guideline on Venous Thromboembolism and Antithrombotic Therapy in Pregnancy:

| Postpartum | Non-pregnancy associated | |

|---|---|---|

| Klima and Snyder | Anticoagulation for at least 7–10 days after fever resolution. If extensive thrombus into renal veins or inferior vena cava is noted, 3 months of warfarin may be indicated. | N/A |

| Bannow and Skeith | For symptomatic postpartum OVT we suggest a short duration (3 months) of anticoagulation, with the addition of antibiotics in the cases of suspected infection (grade 2C). For asymptomatic postpartum OVT, we suggest against the use of anticoagulation unless there is evidence of thrombus extension or pulmonary embolism (grade 2C). | N/A |

| Abbattista et al | 3 months are suggested for symptomatic postpartum OVT, with the addition of antibiotic therapy, if needed. Anticoagulant therapy is discouraged in asymptomatic postpartum-associated OVT with no evidence of thrombus extension or pulmonary embolism. | N/A |

| Kodali et al | The application of DVT guidelines is considered reasonable as outcomes are comparable. There are no definitive guidelines for duration of anticoagulation. Some case reports suggest repeating imaging after 40 or 60 days and stopping anticoagulation if the resolution of thrombus. | N/A |

| Virmani et al | N/A | OVT in the non-obstetrical setting may not require treatment and can be safely followed up with imaging. |

| Rottenstreich et al | Three months duration of anticoagulation appears to be safe. | In non-pregnancy related cases… we suggest considering a longer duration of anticoagulation therapy, up to 6 months, especially in patients with thrombosis extension or positive thrombophilic evaluation. |

| Plastini et al | N/A | Unless an OVT is symptomatic, septic in nature, or associated with another deep venous thrombosis (DVT) requiring treatment, an incidentally detected OVT does not necessarily warrant anticoagulation therapy. |

| UpToDate | We continue anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin or an oral anticoagulant for at least six weeks. Six weeks is likely adequate for pelvic vein thrombosis related to pregnancy or other transient processes. Anticoagulation for longer than six weeks may be appropriate for patients with embolic disease outside the pelvis or with more chronic pro-thrombotic risk factors (including factor V Leiden trait or hypercoagulability related to malignancy). | We continue anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin or an oral anticoagulant for at least six weeks. Six weeks is likely adequate for pelvic vein thrombosis related to pregnancy or other transient processes. Anticoagulation for longer than six weeks may be appropriate for patients with embolic disease outside the pelvis or with more chronic pro-thrombotic risk factors (including factor V Leiden trait or hypercoagulability related to malignancy). |

| Canadian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Clinical Practice Guideline | We recommend anticoagulation for 1 to 3 months. | N/A |

| British Society of Haematology Guidelines | Post-partum ovarian vein thrombosis should be treated with conventional anticoagulation for 3–6 months as for other cases of post-partum VTE (1C). | Incidentally identified ovarian vein thrombosis in patients who have undergone total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with retroperitoneal lymph node dissection does not require anticoagulation except in the rare patient with IVC extension or PE. |

Prognosis

- Complications include:464748

- Ovarian abscess

- Ovarian infarction

- Septic thrombophlebitis

- Thrombus extension (25% to 30%) into the inferior vena cava or left renal vein

- Pulmonary embolization (PE)49

- Uterine necrosis

- Ureteral obstruction, hydronephrosis and renal failure with dialysis

- Morality is about 4%, mainly caused by PE.50

- Routine screening for occult malignancy is not recommended as the incidence of occult cancer is low among patients with a first episode of venous thromboembolism.51

- Risk of venous thromboembolism recurrence:

- The recurrence rate of POVT is unknown, but ovarian thrombosis from all causes may recur at rates similar to deep vein thrombosis.

- Cohort of 219 women with ovarian vein thrombosis and 220 patients with lower extremity venous thrombosis (DVT):

- Median duration of follow-up was 1.23 years for patients with OVT, 3.31 years for patients with DVT.

- During the follow-up period, there were:

- 17 recurrent venous thromboembolism events in 16 unique patients with ovarian vein thrombosis:

- 6 leg DVTs

- 4 PEs

- 1 inferior vena cava thrombus

- 1 renal vein thrombosis

- 1 portal vein thrombosis

- 4 contralateral ovarian vein thromboses.

- 18 total recurrent events in the DVT group:

- 11 DVT

- 3 inferior vena cava IVC thrombus

- 4 four PE)

- 17 recurrent venous thromboembolism events in 16 unique patients with ovarian vein thrombosis:

- Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed no significant difference in survival free from venous thromboembolism recurrence between patients with OVT and DVT.

- For patients with OVT, the recurrence rates were 6.1% at 1 year and 14.3% at 5 years. These percentages did not differ compared with those with DVT.

- Cohort of 35 patients with OVT and 114 female patients with DVT:

- Mean follow-up period of 34.6 +/- 44.3 months

- 3 patients with OVT suffered three recurrent venous thrombi (event rate: three per 100 patient years of follow-up); recurrent thrombosis involved the contralateral ovarian vein, left renal vein, and inferior vena cava.

- This recurrence rate was comparable to patients with lower extremity DVT (2.2 per 100 patient years).