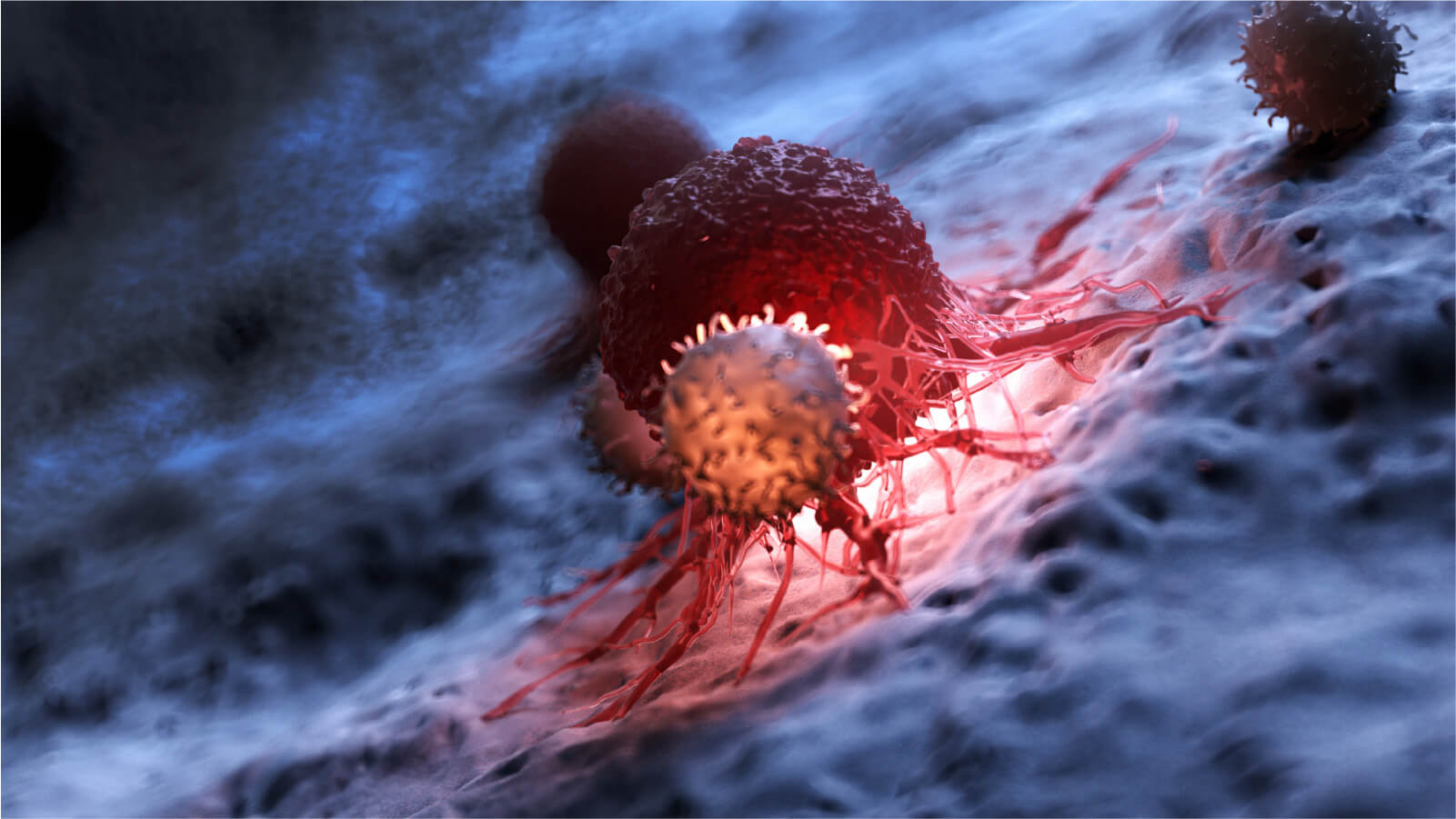

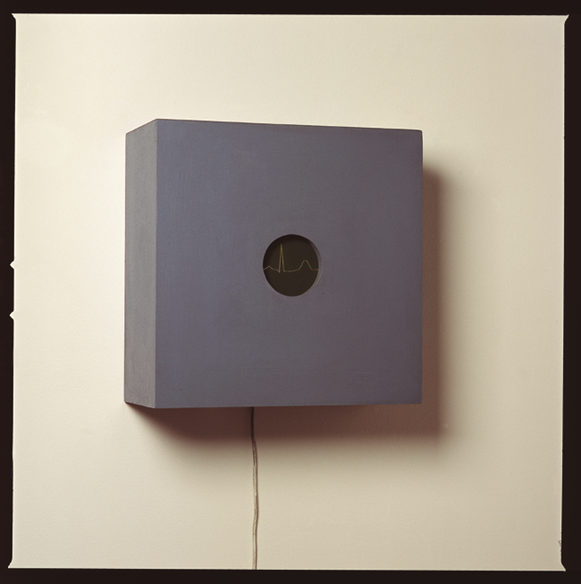

Q1. Describe what you see as accurately as possible.

A1. A blue-coloured square box hangs on a plain cream-coloured wall. There is a a small circular aperture at its centre upon which a line with a tall peak and lower curved lines to right and left is visible. The line appears to be part of an EKG recording. There is also part of a straight line coming from the base of the box.

Q2. Have you ever seen a medical recording presented like this?

A2. No.

Q3. What might be the significance of the wire coming from the bottom of the box?

A3. It looks like an electric wire, so one presumes that it can be plugged in so that the EKG can be illuminated.

Q4. Can you speculate what might be a context for this box hanging on a wall?

A4. As the box is hanging on a plain cream wall, perhaps the context is an art one referencing a common medical investigation for cardiac conditions. It clearly is not a typical way of presenting medical investigations and why would it need illumination?

Notes:

Since the 1960s, pioneering Conceptual artists like O’Doherty sought to challenge traditional forms of art including the painted or sculpted portrait which aimed primarily to present an accurate likeness of the sitter’s face. The context for this portrait was the fact that Duchamp was/is regarded as one of the seminal, most provocative thinkers of 20th century art. He wanted to move art away from the purely ‘retinal’ back to the mind. O’Doherty chose the older artist’s heart, rather than his mind, for the portrait by taking an EKG. When finished, Duchamp said: “Thank you doctor, from the bottom of my heart!”.

Although an admirer and friend, O’Doherty sought with this portrait to refute one of Duchamp’s famous dicta: once art is put on the museum wall, it dies. By ‘animating’ the EKG with an oscilloscope plugged into the wall, Duchamp’s heart, perversely, continued to beat, even following his death in 1968. The EKG became a 16-part series of drawings. One of these slowed Duchamp’s heartbeat so that, conceptually, his ‘life’ was extended and thus a tribute to his lasting influence on 20th and 21st c. art.

One context for the portrait was that the first successful heart transplant by Dr. Christiaan Barnard occurred in 1967. In an article, “The Politics and Aesthetics of Heart Transplants,” (1970), O’Doherty wondered what effect an artificial heart would have on a recipient’s identity. Another context was the medieval practice of preserving the heart of deceased distinguished people, believing it to be the source of immortality, purity and love.

For more information on this and other works by O’Doherty see my “Art Matters: How art and medicine Intersect in the art of Brian O’Doherty/Patrick Ireland.” The Journal of Medical Biography, 2020, Vol 28 (1), 46-51, copyright, the author 2017.