“Establishing a valid diagnosis of anaemia is crucial for treating patients and detecting the range of diseases that could underlie this condition… even in the absence of overt clinical effects, haemoglobin-based thresholds for anaemia are

Lancet Haematol. 2024 Apr;11(4):e253-e264

used as important triggers for investigation and optimisation of underlying contributors… Valid definitions of anaemia are also crucial for guiding population interventions and tracking progress towards global targets.”

Bottom line

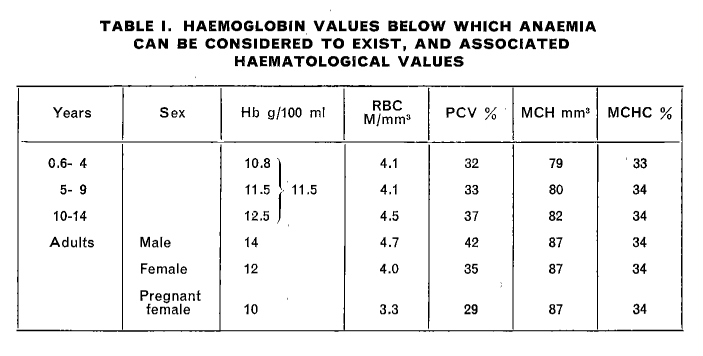

- In 1959, WHO published hemoglobin cutoffs for anemia based on limited data and “personal observations of the Group members”.

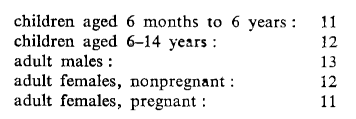

- In 1968, WHO published modified hemoglobin cutoffs based on “more recent data” (they cite 4 studies).

- In 2006, Ernest Beutler and Jill Waalen published a rather harsh critique of the WHO cutoffs in the journal, BLOOD and proposed their own cutoffs based on two data sources.

- In 2024, Braat et al published new hemoglobin cutoffs based on 8 data sources.

- In 2024, WHO published an updated guideline that supported their previous 1969 cutoffs for men and non-pregnant women based on the data sources used by Braat et al as well as some additional data. The report acknowledged that “Data in adult men may suggest a higher haemoglobin cutoff (i.e. 135 g/L) [probably referring to Braat et al] but there was uncertainty in the evidence. The GDG decided to retain the cutoff of 130 g/L for men.”

| Source | Hb Cutoff in Adult Men (g/dL) | Hb Cutoff in Non-Pregnant Adult Women (g/dL) |

|---|---|---|

| WHO 1959 | 14 (no upper age cutoff) | 12 (no upper age cutoff) |

| WHO 1968 | 13 (no upper age cutoff) | 12 (no upper age cutoff) |

| Beutler and Waalen | 13.7 (White; ages 20-59) 12.9 (Black; ages 20-59) | 12.2 (White; ages 20-49) 11.5 (Black; ages 20-49) |

| Braat et al | 13.49 (ages 18–65) | 11.97 (ages 18–65) |

| WHO 2024 | 13 (ages 15-65) | 12 (ages 15-65) |

World Health Organization (WHO) 1958-1959

- WHO first proposed hemoglobin cutoffs to define anaemia in 1959. In 1958, WHO study group on Iron Deficiency Anaemia met in Geneva to “discuss the present states of the problem” of iron deficiency anemia. They published the report the following year in 1959:

- They stated: “to detect and evaluate the anaemia problem of a community, it is necessary to have standards of refence, even if they be somewhat arbitrary. so that not only the severe cases but also the less obvious ones may be discovered… the Group reviewed the large body of haematological data derived from studies of apparently normal persons throughout the world, and from these data and personal observations of the Group members, haematological values, which can be considered as the lower limits of normal for the purpose of determining the presence of anaemia in nutritional surveys, have been selected… lower values than these are suggestive of anaemia.”

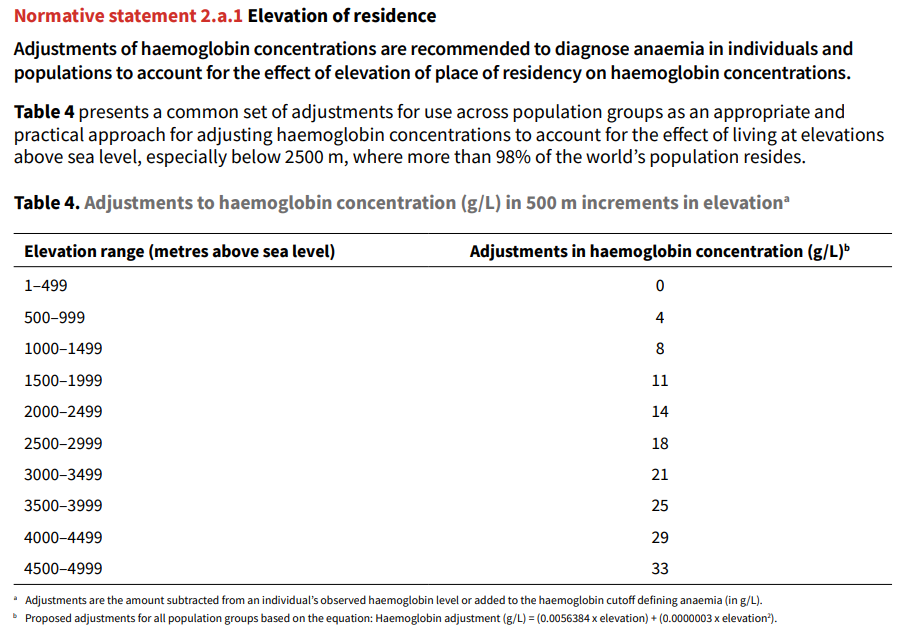

- The authors noted: “Proper upward correction for high altitudes must be made.”

World Health Organization (WHO) 1967-1968

- A WHO Scientific Group on Nutritional Anaemias was convened in Geneva in 1967. They published their report the following year in 1968.

- They stated: “In detecting and evaluating an anaemia problem in a community, reference standards are necessary, even though they may be somewhat arbitrary. The report of the 1958 [1959] WHO Study Group recommended haemoglobin values below which anaemia could be considered to exist. These figures were chosen arbitrarily and it is still not possible to define normality precisely. However, more recent data* indicate that the values given previously should be modified. It is recommended that in future studies, anaemia should be considered to exist in those whose haemoglobin levels are lower than the figures given below (the values given are in g/100 ml of venous blood of persons residing at sea level):”

- The authors wrote: “More than 95% of normal individuals are believed to show haemoglobin levels higher than the values given, which are appropriate for all geographic areas; however, the values must be modified for persons who live at high altitude.”

- Note: In the 2024 WHO report, the authors comment on the 1958 report: “The current cutoffs for men, women, young children, and pregnant women recommended by WHO were first proposed in 1968 after technical meetings of clinical and public health experts working with data from five studies of populations in Europe and North America with predominantly European ancestry. Data from other countries, a wider range of races, and for certain age groups (i.e. infants, young children, adolescents, and elderly people) were not available at the time”.

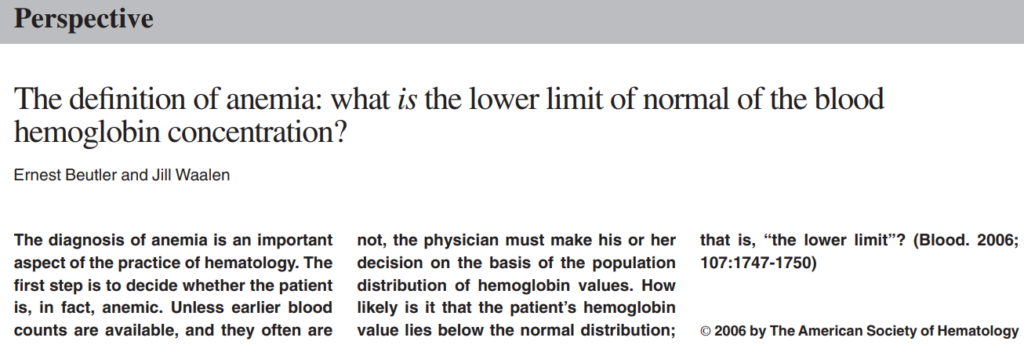

Ernest Beutler and Jill Waalen 2006 paper challenging the WHO criteria for anemia

- Ernest Beutler and Jill Waalen published a paper in 2006 that questioned (quite harshly) the WHO criteria for anemia and proposed their own Hb thresholds based on 2 databases: 1) NHANES-III (the third US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) database, and 2) the Scripps-Kaiser database collected in the San Diego area between 1998 and 2002.

- They wrote:

- “In many studies the definition of anemia used is that suggested by a WHO expert committee nearly 40 years ago.”

- “Bearing the imprimatur of the WHO apparently carries much weight, although, as we shall point out, the numbers so casually presented in that document were based on very few data using methods that were inadequate.”

- “The acceptance of these standards is, indeed, to be decried.”

- Referring to the references that the 1968 WHO report used to derive their Hb thresholds: “The few references that are given to document this choice of numbers are, in general, surveys of the relatively small number of subjects, without documentation of methodology, and without efforts being made to remove patients with anemia in calculating the values.”

- The authors noted:

- No differences in hemoglobin values of men in the age range of 20 to 59 or in women aged 20 through 49.

- Appreciably lower limit of normal of hemoglobin concentrations in African Americans.1

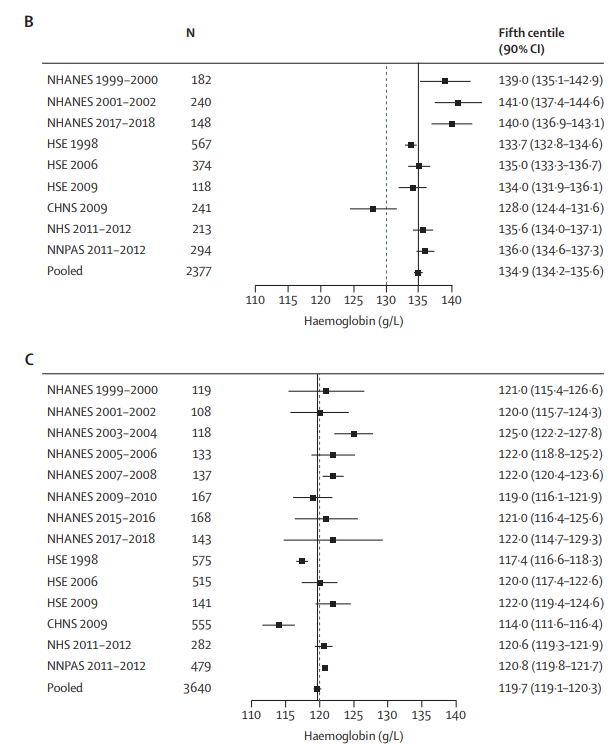

- They proposed the following Hb thresholds for diagnosing anemia:

- The authors wrote: “Based mostly on the larger Scripps-Kaiser database, but confirmed by the NHANES data, it would seem that a hemoglobin concentration below 137 g/L (13.7 g/dL) in a white man aged between 20 and 60 years would have only an approximately 5% chance of being a normal value. For older men, this hemoglobin value would be 132 g/L (13.2 g/dL). The corresponding value for women of all ages would be 122 g/L (12.2 g/dL).”

Braat et al 2024

- Braat et al published a paper that “sought to establish evidence for the statistical haemoglobin thresholds for anaemia that can be applied globally and inform WHO and clinical guidelines”.

- They based their analysis on eight data sources comprising 18 individual datasets that were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. The data sources included:

- Australian Health Survey (AHS)

- Benefits and Risks of Iron interventions in Children (BRISC)

- China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS)

- Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición (ENSANUT)

- Generation R

- Health Survey for England (HSE)

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

- TARGet Kids!

- In the Introduction, the authors wrote:

“WHO’s anaemia definitions aim to reflect the lower fifth centile of the haemoglobin distribution of a reference population of healthy individuals. WHO thresholds were initially proposed in 1958, then updated in 1968, and have remained essentially unchanged since. WHO thresholds were based on studies with restricted measurement of biomarkers of iron and other forms of haematinic deficiency and inflammation. There is limited consensus on anaemia definitions, leading to heterogeneous definitions between sources, expert groups, and public health bodies,6 translating into inconsistent clinical definitions.”

- Results:

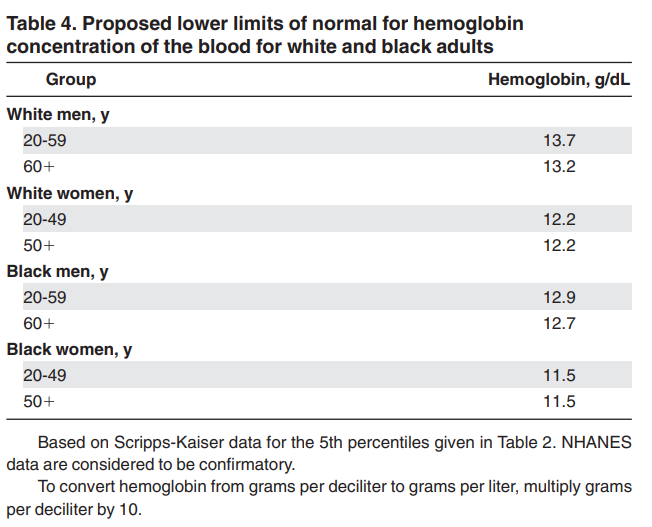

- In pooled analyses of adults aged 18–65 years, the fifth centile was:

- 119·7 g/L (90% CI 119·1–120·3) in 3640 non-pregnant females

- 134·9 g/L (134·2–135·6) in 2377 males

- Fifth centiles in pregnancy were:

- 110·3 g/L (90% CI 109·5–111·0) in the first trimester (n=772)

- 105·9 g/L (104·0–107·7) in the second trimester (n=111)

- Insufficient data for analysis in the third trimester.

- There were insufficient data for adults older than 65 years.

- The authors did not identify ancestry-specific high prevalence of non-clinically relevant genetic variants that influence haemoglobin concentrations.

- In pooled analyses of adults aged 18–65 years, the fifth centile was:

females aged 18–65 years: (B) Individual study and pooled (fixed effect, black line) estimates of the fifth centile of the haemoglobin distribution in the healthy reference population in male adults aged 18–65 years. (C) Individual study and pooled (fixed effect, black line) estimates of the fifth centile of the haemoglobin distribution in the healthy reference population in non-pregnant female adults aged 18–65 years. The dashed line in panels B and C represents the cutoff for anaemia according to the WHO guideline.4

CHNS=China Health and Nutrition Survey. HSE=Health Survey for England. NHANES=National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (USA). NHS=National Health Survey (Australia). NNPAS=National Nutrition and

Physical Activity Survey (Australia).

- In the Discussion the authors wrote:

- “Analyses of genetic associations with haemoglobin concentration across different ancestries show no evidence of the presence of any non-clinically significant high-frequency variants. Collectively, our analyses guide a single set of global definitions for anaemia“.

- “Statistical definitions for anaemia differ between adult women and men”.

- “Our analysis builds on previous studies using chiefly US-based data to estimate fifth centiles of haemoglobin in iron-replete, non-inflamed populations by using multinational datasets with the addition of clinical criteria for health, and covers a broad age range “.2

World Health Organization (WHO) 2014

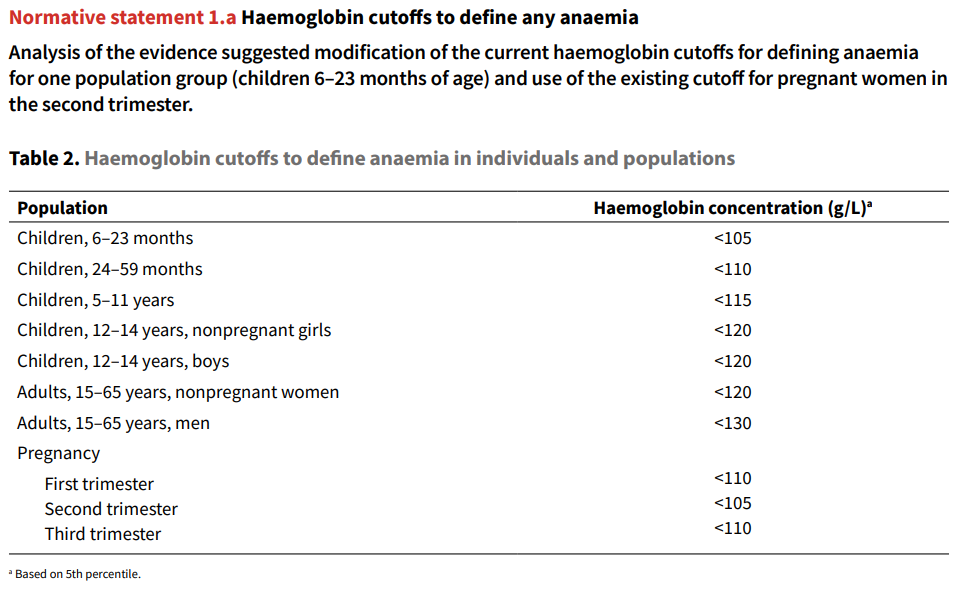

- In 2024, the WHO published an updated Guideline on haemoglobin cutoffs to define anaemia in individuals and populations.

- The authors wrote:

“Briefly, haemoglobin cutoffs were first presented in a 1968 WHO document and were based on four published references and one set of unpublished observations. Definitions for mild, moderate, and severe anaemia were first published in 1989. These were slightly modified in a subsequent publication on nutrition in emergencies, which also proposed a classification to determine the public health significance of anaemia in populations… [A] 2001 document also provided haemoglobin adjustments for those residing or working at elevation and for smoking.”

- In this guideline, the evidence that informed haemoglobin cutoffs to define anaemia in individuals and populations was based on an analysis of haemoglobin data from healthy populations, general population databases, and systematic reviews.3

- The outputs of the statistical approach were haemoglobin values below which only a limited number of healthy individuals would be expected to have anaemia.

- A key consideration was whether to select the 5th or 2.5th percentile for the haemoglobin concentration cutoffs. The choice of percentile entails trade-offs. For this recommendation, the 5th percentile was selected, which is consistent with original WHO guidance for defining anaemia.

- The 5th percentile implies that 95% of healthy individuals would have a higher haemoglobin value, and 5% of healthy individuals would still have a lower haemoglobin value than the cutoff and be falsely diagnosed as anaemic.

- The report acknowledged: “Data in adult men may suggest a higher haemoglobin cutoff (i.e. 135 g/L) [probably referring to Braat et al] but there was uncertainty in the evidence. The GDG decided to retain the cutoff of 130 g/L for men after considering concerns about: iron therapy implications for males; the limited evidence; and the potential unintended consequences of changing the cutoff, such as initiation of iron supplementation programmes in men.”

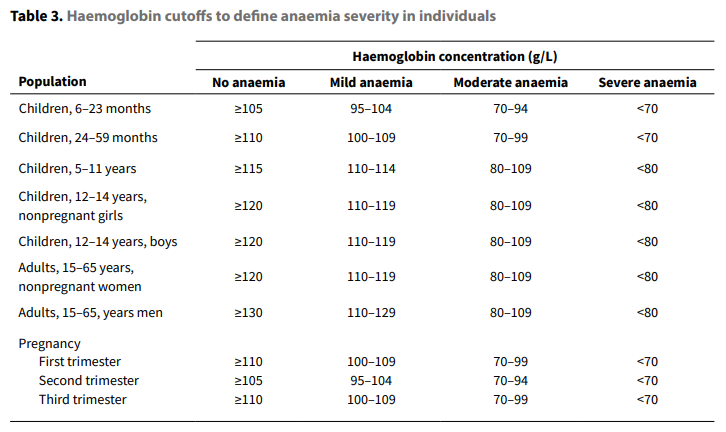

- The 1989 guidance considered anaemia to be mild, moderate, or severe when haemoglobin concentrations are above 80%, between 80% and 60%, or less than 60% of the cutoff levels:4

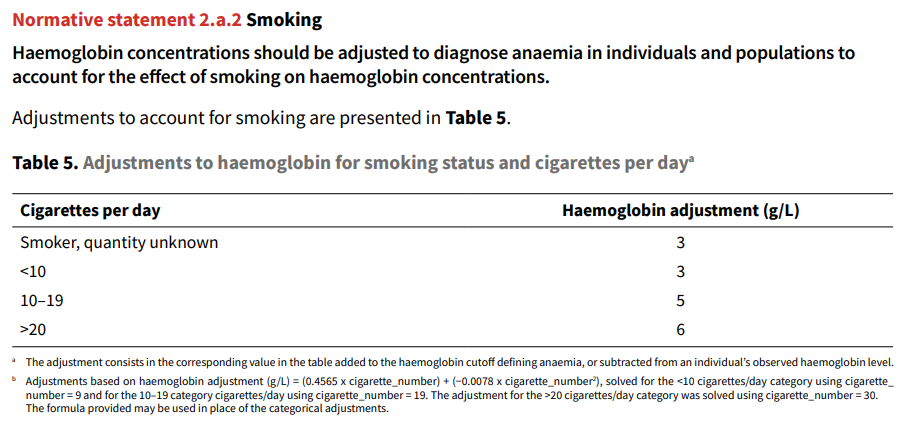

- Adjustments for external factors:

Central and South America. Adjustments provided are to be applied by: subtracting the amount recommended from an individual’s observed haemoglobin level; or adding the amount recommended to the existing haemoglobin cutoff defining anaemia in g/L.

found in women, who have significantly lower rates of smoking than men, although this may be due to

underreporting of smoking quantities. By 30 cigarettes/day the effect size was the same among men

and women (6 g/L).

- Regarding ethnicity, the report stated: “Haemoglobin concentrations should not be adjusted to diagnose anaemia in populations to account for the effect of genetic ancestry/ethnicity/race due to insufficient evidence to change current adjustments and the complexity of operationalization.”