Postscript

Time:

- In 1910, when the first case of sickle cell disease was described at Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago, medicine was undergoing a major transformation: humoral pathology was on its last legs, replaced by a combination of germ theory of disease (and the beginnings of clinical bacteriology) and cell theory (with its implications for pathological growths), and new laboratory techniques were being leveraged for studying and diagnosing disease.

- Among these laboratory techniques was the ability to measure hemoglobin, hematocrit, red blood cell counts and white blood cell counts, and to examine a stained peripheral blood smear under a light microscope.

- According to one historical perspective: “In the first decade of the 20th century medical writers were recommending, for every newly hospitalized patient, a routine hematologic examination, including a blood cell count, microscopic study of both fresh and fixed blood stained with Ehrlich’s triacid stain, and measurement of hemoglobin content… Hematology, though not a specialty, had become an integral part of medicine.”

- Let’s consider the words of one of our protagonists, James Herrick, who wrote in 1907:

Location:

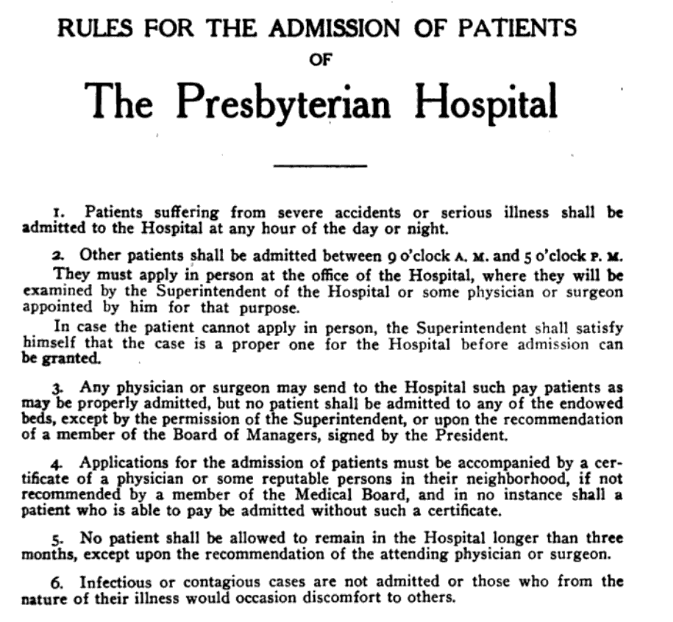

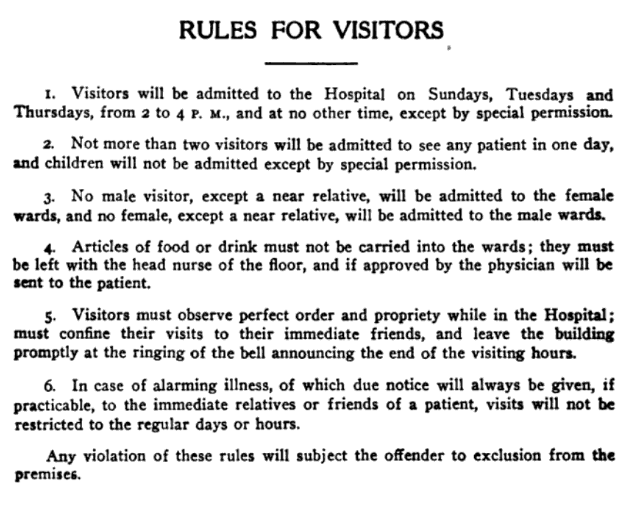

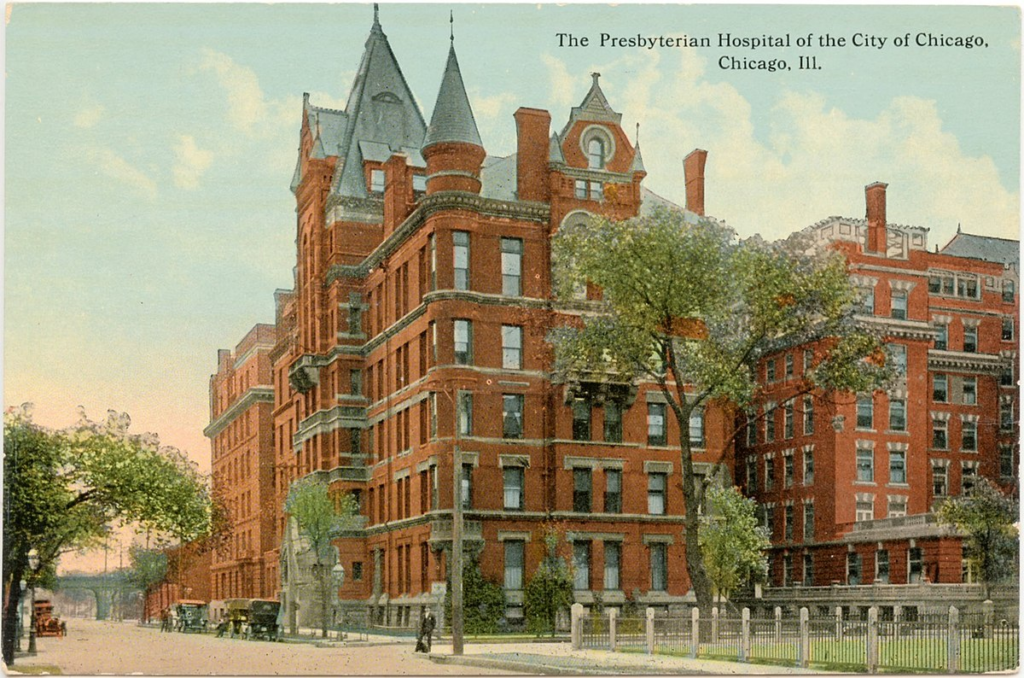

- The discovery of sickle cell disease was made at Presbyterian Hospital, a private hospital affiliated with Rush Medical College.

- Rush Medical College was the first medical school in Chicago.

- The founder of Rush Medical College, Daniel Brainard, MD, named the school in honor of Benjamin Rush, MD, the only physician with medical school training to sign the Declaration of Independence.

- The Rush faculty established a teaching hospital, Presbyterian Hospital, with the support of a local Presbyterian congregation in 1883 (chartered July 21, 1883) as a facility to provide clinical instruction for medical students.

- Rush Medical College was affiliated with the University of Chicago from 1898 to 1941. Following the end of this affiliation, Rush Medical College closed its doors in 1942 for the next 27 years.

- In 1956, St. Luke’s merged with Presbyterian Hospital to form Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Hospital.

- In 1969, Rush Medical College reactivated its charter and merged with Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Hospital to form Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center.

- The institution officially changed its name in September 2003 to Rush University Medical Center.

The patient (Walter Clement Noel, 1884-1916):

- Walter Clement Noel was born on June 21, 1884 on the island of Grenada in the Caribbean, a British colony at the time (19 km wide by 32 km long, and with a population of about 63,000).

- He was born and raised on DuQuesne Estate in the north of the island; his family were wealthy landowners.

- He grew up with his 3 healthy siblings.

- He attended Harrison College in Barbados, where he completed his undergraduate studies in the summer of 1904.

- In September 1904, at the age of 20, Noel sailed from Barbados to New York on the SS Cearense; he developed a leg ulcer during the week-long journey. After customs and immigration processing in New York, he sought medical attention and was treated with topical iodine, and the leg wound quickly healed.

- Noel then traveled by train to Chicago, where he had been accepted as a dental student at the Chicago College of Dental Surgery on the city’s West Side, one of the leading dental schools in the nation. He took a room on West Congress Street, just one block and around the corner from school, in the heart of the Chicago medical district.

- It is believed that Noel was the only student of African descent in his class. The fact that he was well to do and a foreigner may have widened his educational opportunities.

- Noel started school on Oct 5, 1904. Just 3 months later, in late November, he developed respiratory symptoms, now recognized as the leading acute cause of death in patients with sickle cell disease, that persisted for over a month. The day after Christmas, he sought medical attention at the Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago, across the street from his lodgings. There, Dr. Ernest E. Irons, a 27-year-old intern, obtained a history and performed routine physical, blood, and urine examinations.

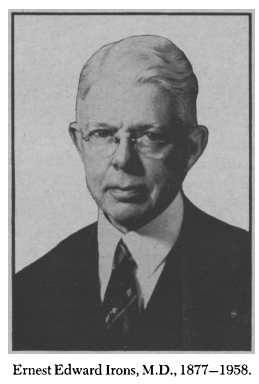

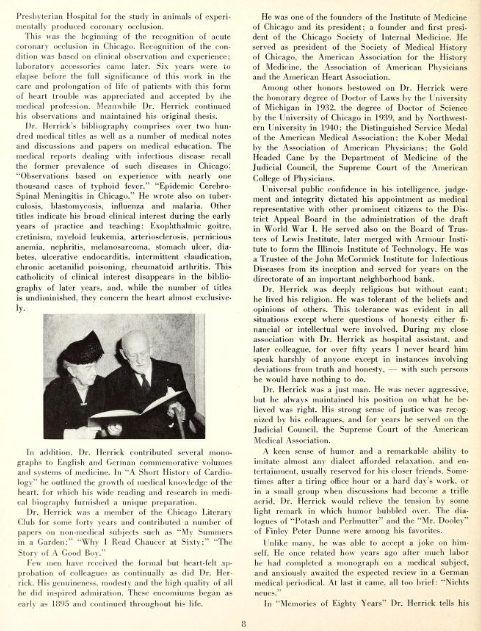

The Intern (Ernest Irons, 1877-1959):

- Dr. Irons was born on a farm in Council Bluffs, Iowa, Feb. 17, 1877.

- He received his:

- Bachelor of science degree at the University of Chicago in 1900, at which time he took a position in bacteriological studies in relation to the effects of Sanitary Canal waters in downstate Illinois.

- Doctor of medicine from Rush Medical College, Chicago, in 1903.

- PhD from the University of Chicago in 1912.

- He continued his studies as assistant in pathology and bacteriology at the University of Chicago from 1902 to 1904, under Professor E. O. Jordan.

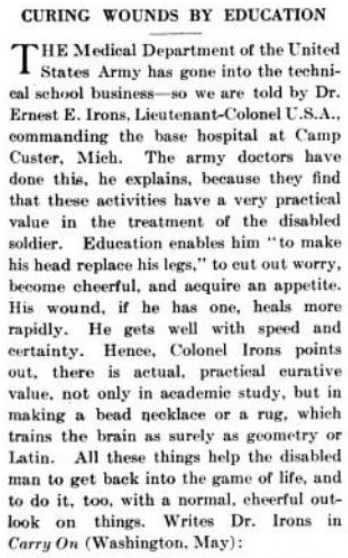

- During World War I, he was a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Medical Corps and was placed in charge of the hospital at Camp Custer.

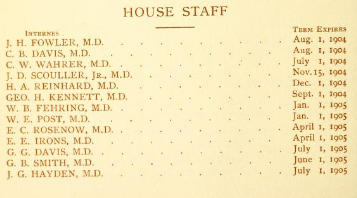

- He completed an internship at Presbyterian Hospital in 1904-1905 (the year he first saw Noel).

- He took a room in the home of his preceptor/mentor, James Herricks, just a few blocks from the medical district, and, shared Herrick’s downtown private office between 1904 to 1909.

- He joined the Medical Staff Presbyterian Hospital in 1907.

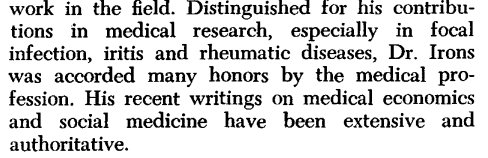

- According to one biography, his primary interests were infectious diseases and bacteriology.1. Indeed, he earned a PhD in bacteriology at the University of Chicago in 1912.

- From 1923 to 1936 he was dean of students and dean of the faculty of Rush Medical College, where for many years he was clinical professor of medicine and chairman of the department.

- In 1941 he held the title of (Rush) clinical professor emeritus at the University of Illinois College of Medicine.

- Irons served as President of:

- Medical Staff, Presbyterian Hospital 1924-1928.

- The board of directors of the Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium (MTS) in 1948.

- The American Medical Association, 1949-1950.

- The American College of Physicians, 1945.

- The American Association for the Study and Control of Rheumatic Diseases in 1934.

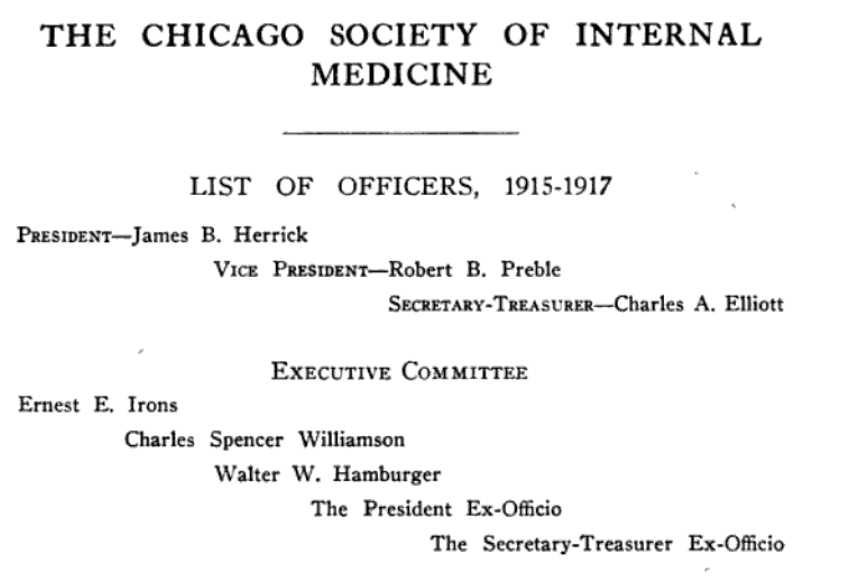

- The Chicago Society of Internal Medicine in 1926.

- The Society of Medical History of Chicago in 1940.

- The Institute of Medicine of Chicago in 1946.

- Cited by the University of California school of medicine in 1946 as the outstanding physician of the year in the United States for service to his patients.

- In 1946 he was awarded the “Goldheaded Cane” of the School of Medicine of the University of California, held also by Dr. James B. Herrick, Chicago, with whom he had been associated many years.

- In 1958 he was presented the Chicago Medal of Merit for his contributions to the city, and the first annual Tuberculosis Institute medal in 1958 for outstanding work in the field.

As can be seen by the above biographical details, Irons was a highly accomplished academic physician, following closely in the footsteps of his mentor, James Herrick, who we will discuss next. Yet, when Irons met his patient Noel in 1904, he was just starting out as a 27-year-old intern:

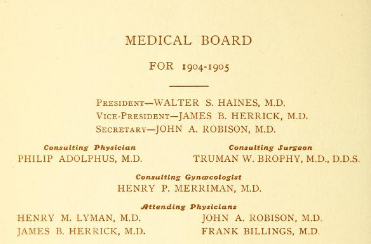

Like his fellow house officers, Irons was male, attired in an all-white uniform, and received free room instead of salary. Interns were typically hired for an 18-month term. Irons would have taken care of patients in an open ward with beds arranged in two rows against the walls and an open central isle which became space for cots bearing overflow patients. Each morning he would prepare the team for daily ward rounds which were led by the Attending Physician, who was a skilled clinician, and attended by medical students and interns. Once the Attending Physician left the hospital after his morning rounds, the senior intern was in charge until the next morning. One of Irons’ Attending Physicians was Dr. James Herrick.

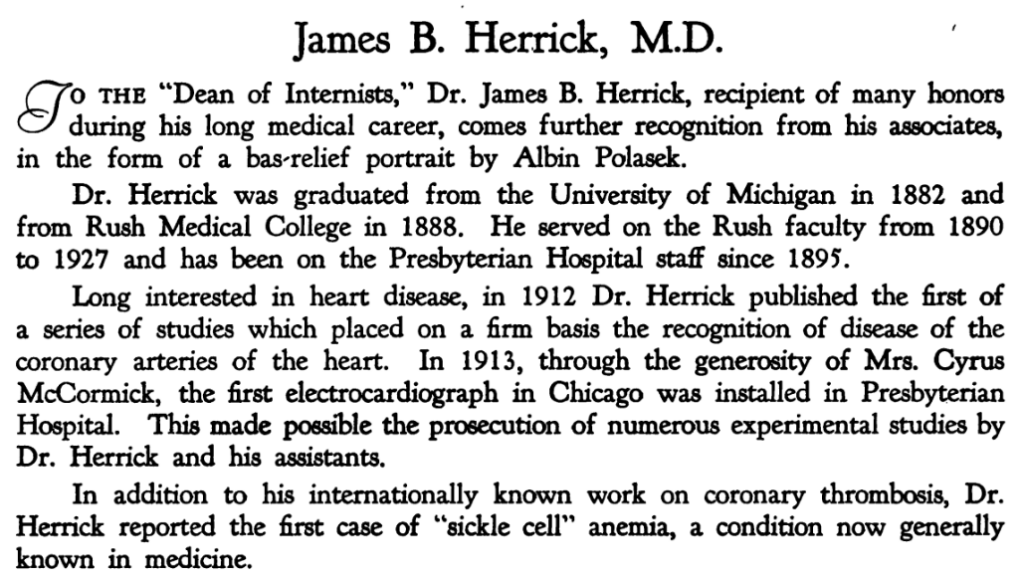

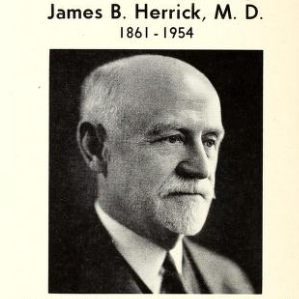

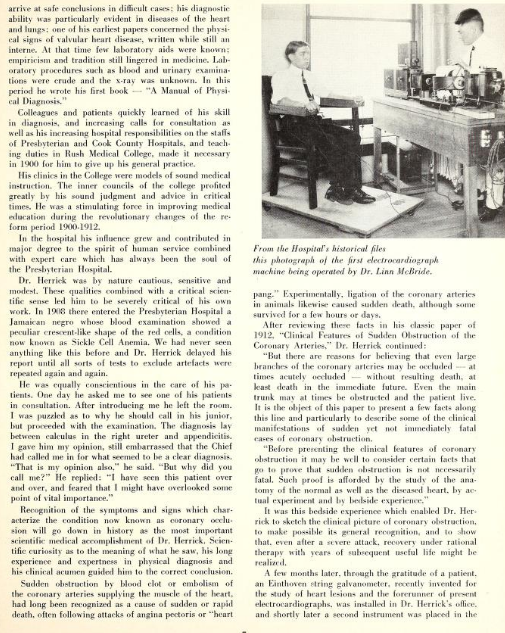

The Attending Physician (James B. Herrick, 1861-1954):

- James Bryan Herrick was born on Aug. 11,1861, in Oak Park, Illinois.

- He graduated from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, with a bachelor’s degree in 1882.

- He taught English, Latin, and Greek for several years in a high school.

- During his final year of teaching, Herrick began his medical studies at Rush Medical College in Chicago. He received his Doctor of medicine from Rush Medical College, Chicago, in 1888.

- After completing an internship at Cook County Hospital, Herrick was appointed to the staffs of Cook County Hospital and Presbyterian Hospital, and he became an instructor and subsequently professor of medicine at Rush.

- As was customary at the time for academic physicians, Herrick also had an independent private practice. In 1900, however, he announced to his patients that he was transitioning from family practice to consultation and hospital practice.

- His first book, A Manual of Medical Diagnosis, was published in 1895 when he was age 35.

- He was Attending Physician at Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago for 50 years (1895 to 1945).

- He served as president of:

- Medical Staff, Presbyterian Hospital 1908-1913

- The Association of American Physicians

- The American Heart Association

- The Institute of Medicine of Chicago

- The American Association of the History of Medicine

- Herrick was the recipient of the:

- George M. Kober Medal from the American Medical Association in 1930.

- The American Medical Association Distinguished Service Medal.

- Herrick was named:

- The Harvey Society Lecturer in 1931.

- Master of the American College of Physicians in 1940.

- Herrick is best known for his report on coronary artery disease, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1912.2 The prevailing thought at the time was that coronary obstruction typically resulted in sudden death. Herrick showed that angina was not always fatal. One biographer wrote: “Herrick’s long-standing interest in diseases of the heart garnered him attention as a heart specialist, which would be further amplified by his numerous publications on angina and coronary thrombosis.”

Irons meets Noel:

On Dec 26, 1904, Noel decided to seek medical attention several weeks after feeling unwell. The first clinical encounter involved Noel and the young intern, Earnest Irons at Presbyterian Hospital, Chicago.

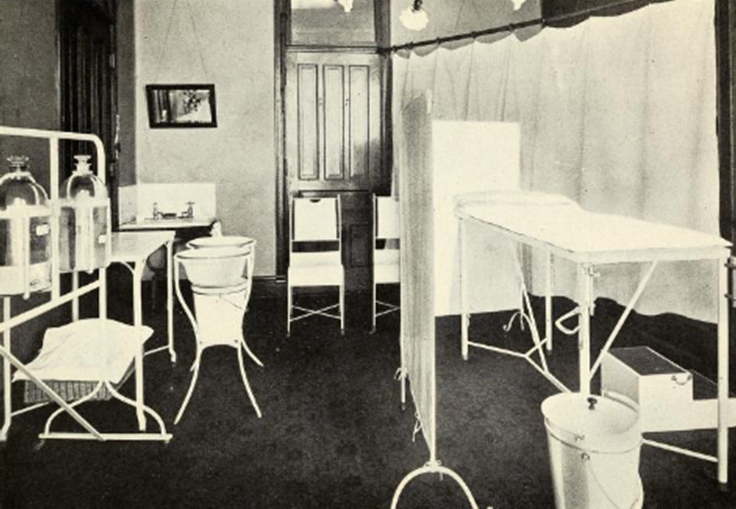

- Irons performed a history and physical exam in an examining room similar to that shown below.

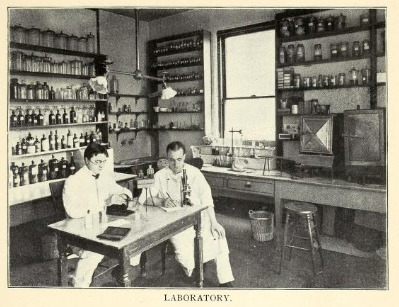

- Irons then measured Noel’s Hb, red blood cell count and white blood cell count, and performed a peripheral blood smear, which was a relatively recent addition to the clinical testing battery. He would likely have performed his studies in the clinical lab shown below.

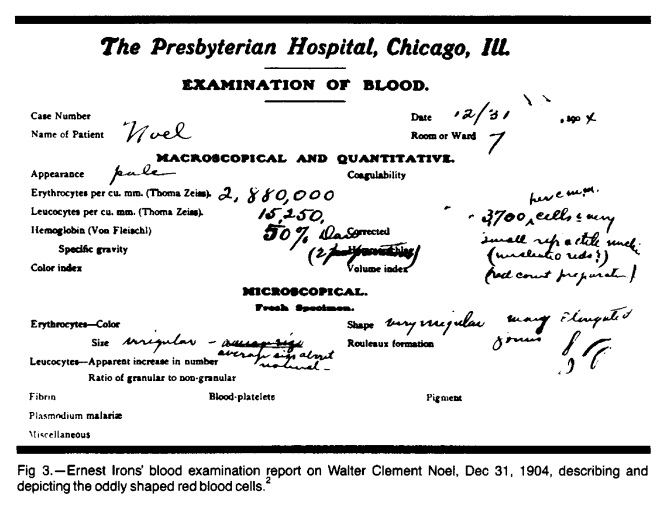

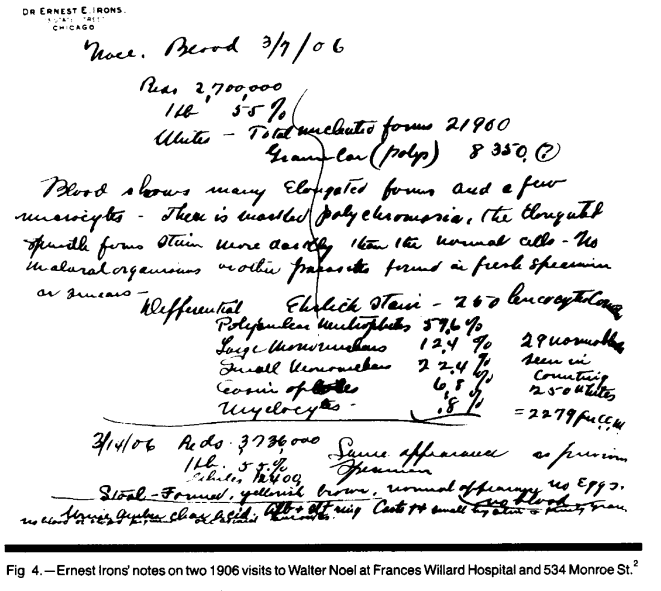

- Irons recorded his findings in handwriting:

- Irons discussed the case at length with Herrick, his supervising physician.

- Their differential diagnosis at the time included hookworm disease, yaws, syphilis, ground itch, malaria, intestinal parasites, and the effects of coal tar medicinal preparations. However, a thorough search for potential causes of these oddly shaped cells was unrevealing.

- With supportive care, Noel slowly recovered his strength and overcame the respiratory infection. His physicians discharged him on Jan 22,1905, still without a clear diagnosis.

- Irons (and Herrick by proxy) followed Noel for more than two years but ultimately lost track of him without establishing a diagnosis.

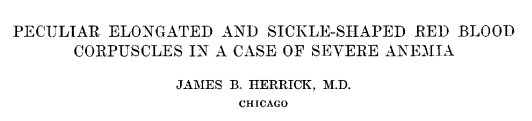

Herrick’s paper:

Relevant information:

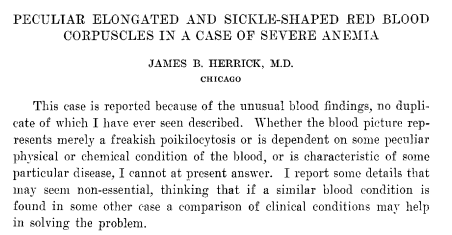

- “This case is reported because of the unusual blood findings, no duplicate of which I have ever seen described.”

- “Whether the blood picture represents merely a freakish poikilocytosis or is dependent on some peculiar physical or chemical condition of the blood, or is characteristic of some particular disease, I cannot at present answer.”

- History:

- No family history of similar complaints.

- 1 year history of palpitations and shortness of breath which the patient had attributed to excessive smoking.

- Admitted to past episodes of scleral icterus.

- “There was never any rheumatism or other joint trouble”

- “On landing in New York in September, 1904, he had a sore on one ankle for which he consulted a physician. Tincture of iodine was applied and in a week the sore had healed, leaving a scar similar to the others on the limbs.”

- “For the past five weeks he had been coughing” with chill, followed by fever

- “It was this cough and fever for which he wished treatment at the hospital, and of which he chiefly complained, though he mentioned also that he felt weak and dizzy, had headache and catarrh of the nose”

- Physical examination:

- The temperature on admission was 101 F.

- “Tinge of yellow in the sclera”

- “The nose showed chronic and acute rhinitis.”

- There were about twenty scars from previous ulcers.

- “Numerous rales, mostly of the moist variety, were heard scattered throughout the chest.”

- “A soft systolic murmur, not well transmitted in any direction, was heard over the base of the heart.”

- Labs:

- Urine with a few granular and hyaline casts

- The blood-count on Dec. 20, 1904:

- Red corpuscles, 2,570,000

- white corpuscles, 40,000

- hemoglobin (Dare) 40 per cent

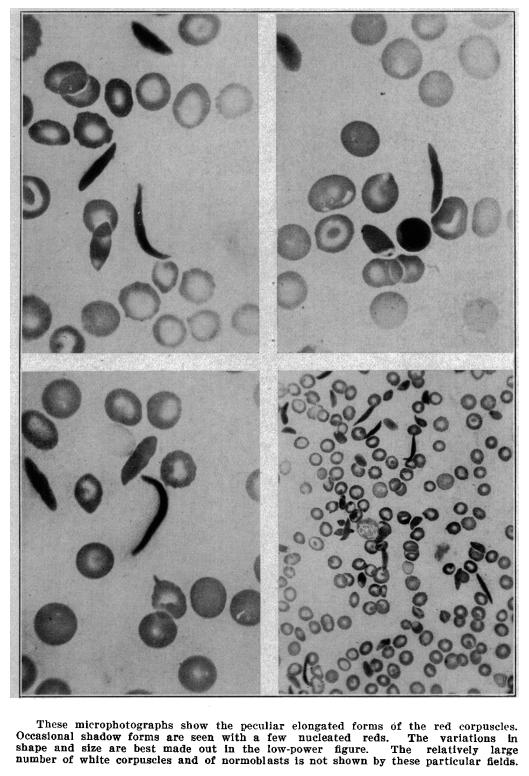

- Peripheral smear:

- “The red corpuscles varied much in size, many microcytes being seen and some macrocytes. Polychromatophilia was present. Nucleated reds were numerous, 74 being seen in a count of 200 leukocytes, there being about 5,000 to the c.mm. The shape of the reds was very irregular, but what especially attracted attention was the large number of thin, elongated, sickle-shaped and crescent-shaped forms. These were seen in fresh specimens, no matter in what way the blood was spread on the slide and they were seen also in specimens fixed by heat, by alcohol and ether, and stained with the Ehrlich triacid stain as well as with control stains. They were not seen in specimens of blood taken at the same time from other individuals and prepared under exactly similar conditions. They were surely not artefacts, nor were they any form of parasite… In a few of the elongated forms a nucleus was seen.”

Follow-up:

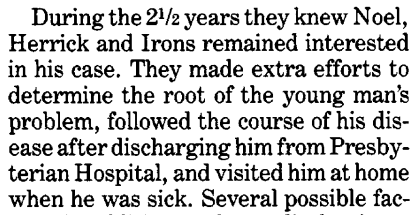

- Over next 2 and a half years, Noel experienced several illnesses.

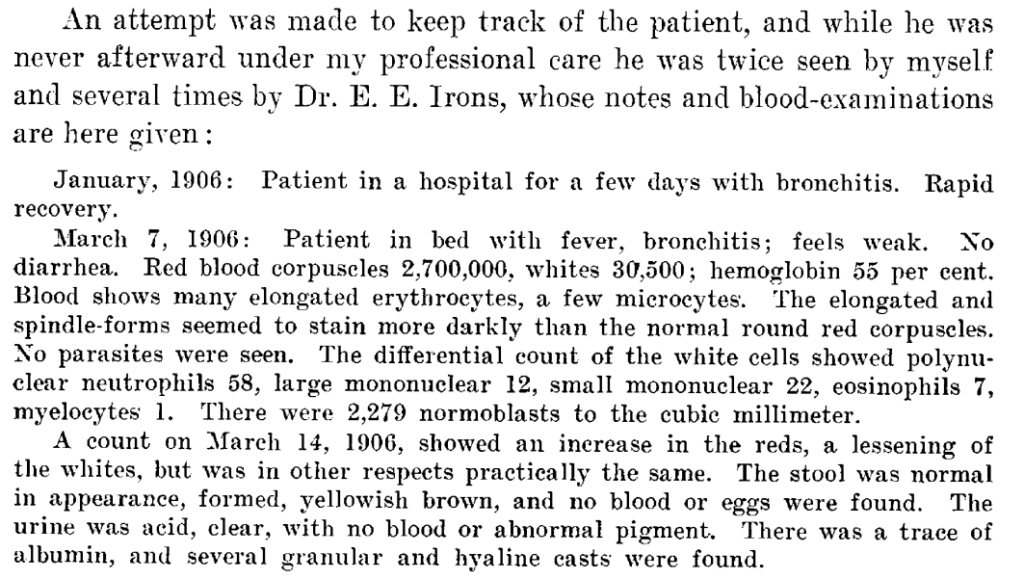

- Herrick wrote that “An attempt was made to keep track of the patient, and while he was never afterward under my professional care he was twice seen by myself and several times by Dr. E. E. Irons, whose notes and blood-examinations are here given” (Irons kept dutiful case notes and gave all these to Herrick at the end of his training):

- January, 1906: Patient in a hospital (nearby Frances E. Willard National Temperance Hospital). Rapid recovery.

- March 7, 1906: Patient in bed with fever, bronchitis; feels weak.

- May 1906: Patient was seen by Dr. Irons [Irons also made a house], who found him with some fluid in the left knee-joint; the temperature was 100. Gonorrhea was denied. The patient ascribed the joint trouble to a wrench of the knee a few days before. He recovered after ten days of rest in bed.

- In April 1907, the young man reported that he had been laid up in a hospital from Dec. 26, 1906, to Feb. 26, 1907, with what he called muscular rheumatism.

- Irons saw Noel one last time, in April 1907, to discuss progress made since his February discharge from Frances Willard Hospital. Noel reported feeling much better at that time, except for some lingering shortness of breath.

- Despite his illnesses, Noel graduated from dental school with his entering class on May 28, 1907.

- Noel then returned to Grenada to set up a private general dentistry practice in the capital city of St George’s. His mother owned the building where the practice was located; Noel lived upstairs, and his offices were at street level.

- He owned his own dental equipment and, by 1915, had hired a young man in the office as his assistant.

- He never married. In 1915, Noel drafted a will, suggesting the possibility that he was becoming worried about his health.

- In April 1916, Noel overexerted himself, with fatal consequences: he attended a horse race on the far side of Grenada, traveled a considerable distance home, and bathed, all on the same day. He then developed a “chill,” followed by a serious respiratory infection. Noel’s condition steadily worsened, and he died in May 2 1916 in his home, at the age of 32 years. Eldon Marksman, his assistant, reported the death, which Dr. G. W. Paterson certified as having been caused by “asthenia from pneumonia” (acute chest syndrome?).

- Noel is buried in a churchyard that overlooks the Caribbean Sea in the parish of Sauteurs next to his sister Jane, who also died in early adulthood of pulmonary disease, and his father, who died at age 36 years, ostensibly from kidney disease.

Credit for the discovery:

James Herrick was the sole author on the paper that described Noel’s condition.

By today’s standards, that may seem unfair. After all, Ernest Irons did most if not all the legwork, documented the results and no doubt participated in many discussions with his mentor, Herrick, about the clinical implications of their findings. A full 6 years passed between the first clinical encounter with Noel and publication of the paper. Irons was no longer a subservient intern, but now on staff at the hospital. Yet the power dynamic remained firmly entrenched: Irons was an Assistant Physician, which was the lowest rung on the ladder, followed by Attending Physician and Consulting Physician, while Herrick was President of the Medical Board. We see Herrick’s seniority play out time and time again during their careers. Herrick always seemed to be one step ahead of Irons. For example, Herrick served as President of the Chicago Society of Internal Medicine, with Irons playing a subsidiary role on the executive committee:

Medical hierarchy mattered and it was likely to have played into Herrick’s decision (whether conscious or not) to exclude Irons as an author.

The 1910 paper opens with liberal use of the first person: “This case is reported because of the unusual blood findings, no duplicate of which I have ever seen described. Whether the blood picture represents merely a freakish poikilocytosis or is dependent on some peculiar physical or chemical condition of the blood, or is characteristic of some particular disease, I cannot at present answer. I report some details that may seem non-essential, thinking that if a similar blood condition is found in some other case a comparison of clinical conditions may help in solving the problem. But when Herrick turns to the follow-up of the patient, he twice references Irons participation in the care of Noel:

- “An attempt was made to keep track of the patient, and while he was never afterward under my professional care he was twice seen by myself and several times by Dr. E. E. Irons, whose notes and blood-examinations are here given.”

- “In May, 1906, the patient was seen by Dr. Irons.”

One never gets a sense that Irons felt cheated. He went on to a very successful career as a thought leader, teacher and administrator. In a piece titled “The Presbyterian Hospital and the Progress of Medicine 1883-1943”, he celebrated the 60th anniversary of the founding of the Presbyterian Hospital of the City of Chicago. He focused mostly on advances in bacteriology:

As he gets closer to the time that Herrick published his case report on sickle cell disease, he does not even mention advances in hematological diagnosis, let alone his one findings on Noel, but rather espouses advances in biological chemistry and X-rays at the turn of the 20th century:

Finally, he moves to the more recent advances of antibiotic use and blood transfusion:

The written record shows that Irons was consistently deferential to Herrick. In an obituary, he wrote:

Seldom are there combined in one man so many attributes of greatness as were exemplified by Dr. Herrick – scholarship, culture, professional competence, thoroughness, scientific interest, integrity. And yet, his was the greatness of simplicity.

Transactions of the Association of American Physicians. 1954;67:15-19

In one of the rare recorded reflections on his description of sickle cell disease, Irons admits to participating in the work up of the patient, Noel, but then seems to cede credit for the discovery to Herrick:

The collection of Irons’ papers at the Rush University Medical Center Archives include medical writings on bacteriology and pneumonia. Other writings include articles on medical education, socialized medicine, and history; addresses given by Irons; and personal diaries kept while abroad, 1948 and 1958. Yet there is no mention of his work with Herrick on describing the first case of sickle cell disease, despite enormous contemporaneous advances in the field.

In an obituary in the Journal of the American Medical Association, there was no mention of his work on sickle cell disease:

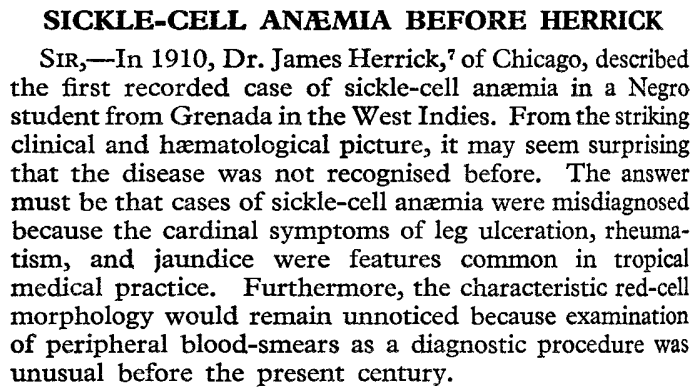

Sickle cell disease before Herrick:

Sickle cell disease after Herrick:

According to Todd Savitt:

Medical case reports are intentionally cold, analytical, scientific. Their authors’ goal is to present the facts of a case in order to understand a patient’s situation, illustrate a specific point, provide information to medical colleagues so they can determine if they have encountered similar cases, and/or alert physicians to be on the lookout for similar cases. Chicago doctor James B. Herrick published his report of a patient with severe anemia and odd crescent-shaped red blood cells in 1910 because he and his colleague Ernest E. Irons had never come upon a case like it before and wanted to put out the information to other practitioners. His plan worked. A fourth-year medical student at the University of Virginia School of Medicine read that report and, four months later, published his own paper about a patient at the university’s hospital with similar findings. Those two cases formed the basis for the third and fourth case reports in 1915 and 1922, and the steady stream of case reports and analytical articles that followed in the subsequent decade, discussing the new disease that came to be known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia is now recognized to include several types of hemoglobinopathies that are called, in aggregate, sickle cell disease (SCD).

J Natl Med Assoc. 2014 Summer;106(1):31-41

- The second case was a 25-year-old female, published only 3 months later, who had been observed for some years in the wards of the Medical College of Virginia.3

- The third case reported a 21-year-old female in 1915, again with a characteristic blood film, but included a report on the father whose fresh blood film was normal although when a blood preparation was sealed and observed after several days, there were similarly abnormal red cells.4

- The fourth case, of a 21-year-old male, reported from Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1922 was the first to use the term ‘sickle cell anaemia’ and noting the African origin common to the first four cases, led to the misconception that the disease was limited to this group.5

- By 1933, more than fifty SCD articles had appeared in print, but though the disease was well-described, it remained puzzling to clinicians and medical scientists.

- In 2014, Savitt wrote:

- “Physicians were just learning to include SCD in their differential diagnoses, so they sometimes failed to make the correct judgment the first time (or second or third) a patient was seen. As new articles appeared, physicians had more opportunity to learn about SCD and incorporate it into their diagnostic thinking.”6

- “Physicians could offer few treatments to relieve the various disabling symptoms of SCD. Reliable analgesics for pain relief, salves and healing creams for leg ulcers, and antibiotics for respiratory and other intercurrent infections had not yet been developed, leaving patients to suffer the natural consequences of their illness. They almost certainly tried various home remedies and perhaps patent medicines, but no published case histories of the time recorded such information.” 7

Appendices:

from Presbyterian Hospital of the City of Chicago. Woman’s Auxiliary Board.