About the Condition

Description/definition:

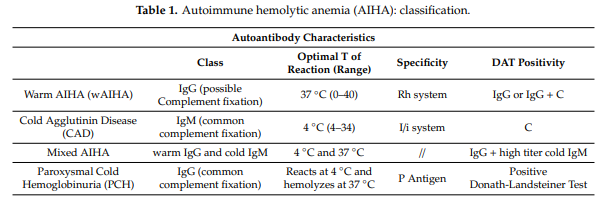

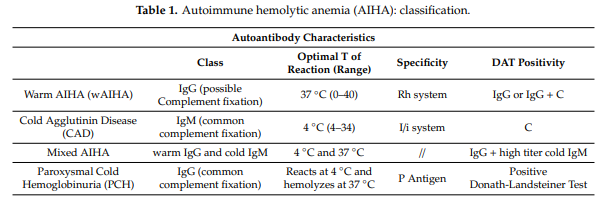

Cold autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is a condition of acquired uncompensated destruction of red blood cells (RBCs) by autoantibodies to RBC antigens that bind optimally to RBCs at 0-4 degrees C (32-39.2 degrees F), but also react at temperatures above 30 degrees C (86 degrees F).

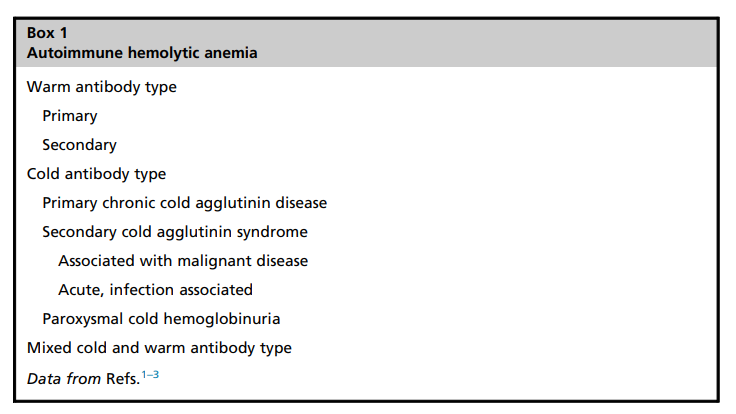

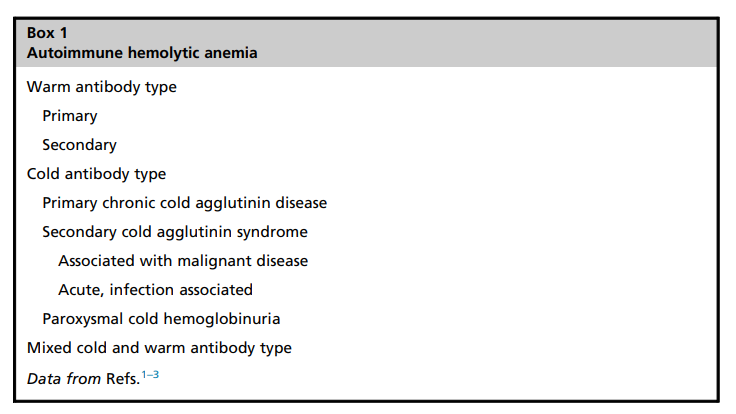

Cold autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) includes:

- Cold agglutinin disease (CAD)

- Paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria

CAD is traditionally classified as:

- Primary or idiopathic

- > 90% of patients with primary CAD are reported to have clonal expansion of kappa-positive B cells in the bone marrow and a monoclonal immunoglobulin M (IgM)-kappa paraprotein

- Secondary or acquired, caused by

- Infection

- Malignancy, especially B cell lymphoproliferative disorders

- Autoimmune disease

According to a recent international consensus, CAD is defined as “an AIHA with a monospecific direct antiglobulin test (DAT) strongly positive for C3d (and negative or weakly positive with IgG [immunoglobulin G]) and a cold agglutinin (CA) titer of 64 or greater at 4°C. We recognize that there may be occasional cases with CA titer<64. Patients may have a B-cell clonal lymphoproliferative disorder (LPD) detectable in blood or marrow but no

clinical or radiological evidence of malignancy.”1

CAD accounts for approximately 15–25% of autoimmune hemolytic anemias (AIHAs). Prevalence of 5 to 20 cases per million and an incidence of 0.5 to 1.9 cases per million per year.

Pathophysiology:

Cold agglutinin disease caused by complement-fixing antibody (monoclonal immunoglobulin M [IgM] in about 90% of cases) that typically binds to antigens of the I blood group system (rarely the Pr antigen) with maximal reactivity between 0 and 4 degrees C (32-39.2 degrees F), leading to complement-mediated extravascular (and to lesser extent intravascular) hemolysis. Approximately 90% of cold agglutinins have anti-I specificity, while the remaining usually have anti-i specificity.

In primary cold agglutinin disease (CAD):

- Bone marrow displays a characteristic histomorphologic, immune phenotypic, and molecular pattern that has been designated CA-associated LPD.

- > 90% of patients reported to have clonal expansion of kappa-positive B cells in bone marrow and a monoclonal IgM-kappa paraprotein

- Monoclonal cold autoantibody is often encoded by IGHV4-34 and targets I antigen

Clinical Presentation:

- Onset is usually gradual

- Patients may present with symptoms and signs of anemia, including

- Fatigue (attribute to both anemia and complement activation)

- Weakness

- Dizziness

- Dyspnea

- Pallor

- Patients may present with symptoms and signs of hemolysis, including

- Jaundice

- Dark urine

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Splenic fullness

- Patients may also present with history of cold-induced symptoms, resulting from agglutination of erythrocytes in the acral circulation, including:

- Episodic acute hemolysis; including dark colored urine after exposure to cold, febrile illness, or major trauma

- Using warm clothing or staying indoors in cold weather

- Seasonal variation in symptom severity in cool climates

- Acrocyanosis – in 40-50% of patients

- Raynaud’s phenomenon

- Livedo reticularis

- Patients may present with additional symptoms of underlying disease

- Complement-driven exacerbation of hemolysis is common during febrile infections and other conditions with acute-phase reaction.

- Physical findings include:

- Pallor

- Jaundice

- Splenomegaly (rare)

- Acrocyanosis (bluish appearance of extremities such as toes, fingers, tip of nose, or ears)

- For further information about the physical diagnosis in cold agglutinin disease, click here.

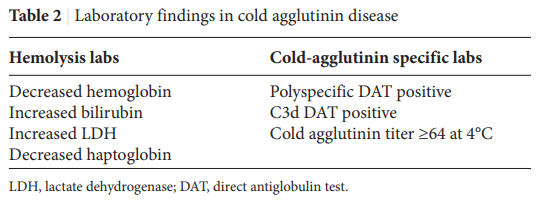

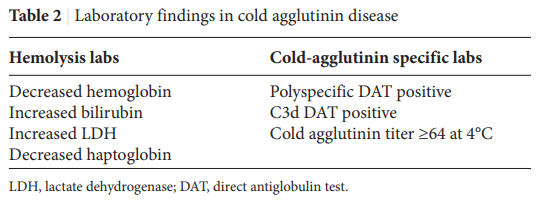

- Labs show:

- Anemia

- About 25% found to have severe anemia, defined as hemoglobin (Hb) < 8.0 g/dL.

- About 35% have moderate anemia, defined as Hb 8.0-10.0 g/dL).

- About 25% have mild anemia (Hb > 10.0 g/dL).

- About 10% have compensated hemolysis (no anemia).

- Hemolysis

- Blood tests

- Urine tests – hemoglobinuria has been reported in at least 15% of the patients.

- Anemia

- Positive DAT (see next section)

Diagnosis:

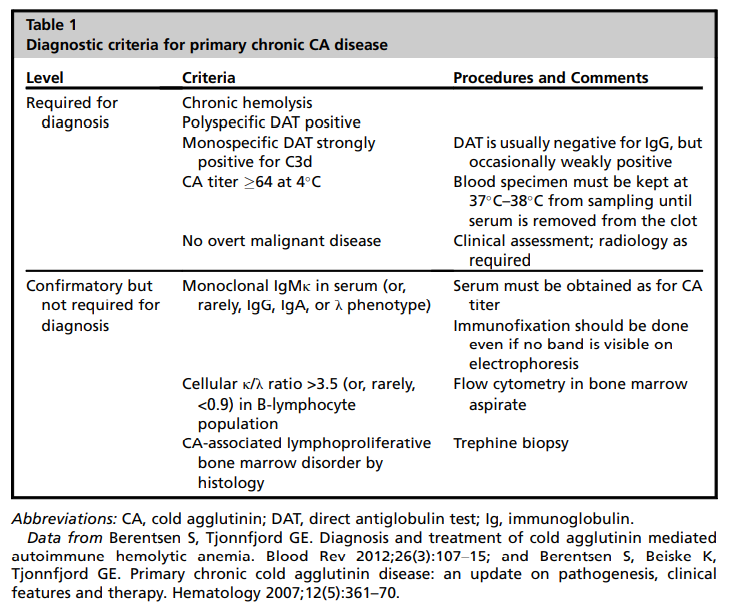

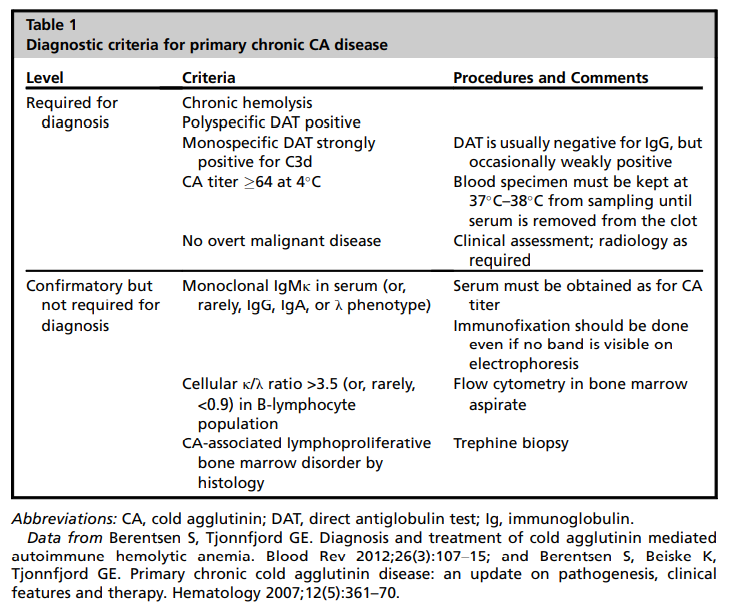

Clinicopathological diagnosis based on demonstrating hemolytic anemia and serological evidence of ant-red blood cell autoantibodies by direct antiglobulin test (DAT).

Suspect diagnosis in patient with:

- Compatible history

- Unexplained chronic anemia (median hemoglobin of 9-10 g/dL in the US population)

- Chronic hemolysis

Confirm diagnosis if:

- DAT positive for complement with or without immunoglobulin (Ig) G – up to 22% of CAD cases may have a positive anti-IgG DAT, in addition to a positive anti-C3d DAT.

- High titer cold agglutinin

- >1:64 or more.

- Semi-quantitative assay based on ability of antibodies to agglutinate erythrocytes at 4°C).

- Note: most defining criteria of CAD do not require that anti-I/anti-i specificity be present.

Optional confirmatory tests:

- SPEP showing monoclonal IgM-kappa in serum.

- Cellular kappa to lambda ratio > 3.5 in B cells (fluorescence activated cell sorting [FACS]).

- Cold agglutinin-associated lymphoproliferative disorders on bone marrow histology.

Once diagnosis of CAD is established, evaluate for secondary conditions; tests may include:

- Serum Ig and electrophoresis with immunofixation to identify underlying clonal bone marrow lymphoproliferative disorder often associated with primary CAD.

- HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C testing.

- Anti-double-stranded DNA and antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing to help diagnose autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

- Computed tomography (CT) scan of chest, abdomen, and pelvis to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment:

- Treat if symptomatic anemia, severe circulatory symptoms, transfusion dependence.

- > 70% of patients reported to require therapy.

- Treatment decisions are based on expert opinion; prospective studies to support benefit are lacking.

- Nonpharmacological measures (especially avoidance of cold) are cornerstone of management. Has been shown to alleviate symptoms and may prevent severe exacerbations of hemolytic anemia.

- Supportive transfusions may be required

- Consider using blood warmer when transfusing RBCs.

- Blood bank testing for underlying alloantibodies and crossmatch testing should be performed at 37°C.

- If the cold agglutinin has a broad thermal amplitude, obtaining crossmatch compatible blood may be a clinical challenge.

- Therapies may be aimed to suppress production of aberrant IgM or to inhibit complement-mediated destruction of red blood cells (RBCs)

- Consider corticosteroids (prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day) or plasmapheresis as a temporary measure to remove IgM autoantibodies, if anemia is severe or life-threatening.

- Although corticosteroids are a rapid and effective treatment for warm AIHAs, they have not been shown to be as effective in CAD. Retrospective studies have found that <15% of patients respond to corticosteroids, and they require higher doses to maintain remission.

- Typically treated with one of the following regiments:

- Rituximab

- Rituximab plus bendamustine

- Rituximab plus fludarabine

- Consider complement system-targeting monoclonal antibody:

- Eculizumab

- Sutimlimab-jome (Enjaymo), which has been FDA approved to decrease need for RBC transfusion due to hemolysis in adults with CAD.

- Surgical intervention, including splenectomy, has been shown to be effective only in patients with IgG-mediated CAD, which represents only approximately 3.5% of patients.

Prognosis:

- The median overall survival of patients with CAD has been estimated to be 12.5 years, similar to that of a general age- and sex-matched population.

- Estimated risk of transformation of the lymphoproliferative bone marrow disorder to aggressive lymphoma is about 3% to 4%.

- Increased risk of venous thromboembolism.

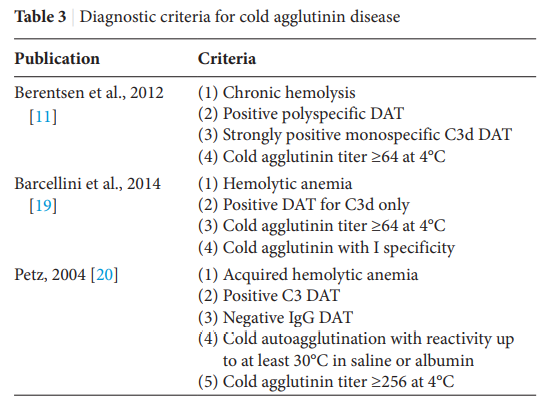

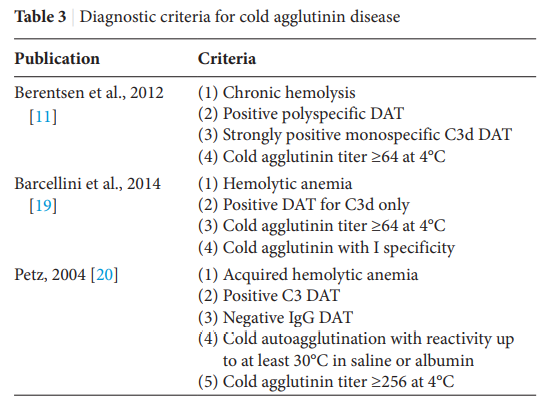

Tables related to classification and diagnosis