Talk comes cheap in the public sphere. But the speeches and monologues that define art, politics, and debate offer many clues into human thought. Out of all these hints, the concept of blood is one of the most interesting — and its repeated use throughout history suggests an important, evolving meaning. Oratory is both an act of artistic expression and a beast of convenience. Great speakers paint scenes and evoke ideas by choosing their words with care. But they’re bound by the palettes of their environments: education, cultural exchange, migration, and the other forces that shape language. Does blood carry some universal theme despite these dynamics? Or is it susceptible to changing times like any motif? Let’s travel back in time to see how speakers and artists have used the concept.

Blood in National Speechcraft

Like other themes, blood has a multipurpose oratorical use. It’s not always a straightforward allusion to the fluid running through your veins.

Latin Epic Poetry and Modern Race Relations

Google the terms “blood” and “speech,” and one of the first things you’ll find is a 50-year-old controversy.

In 1968, Enoch Powell, a British Member of Parliament, spoke at a Conservative Party meeting. At the time, the UK was reeling in the wake of recent bus boycotts, riots, and other discontent. Many citizens — and lawmakers — wanted more social equality.

But not everyone was having it, and Powell came out against legislation prohibiting discrimination. His anti-immigration tirade, the infamous “Rivers of Blood” speech, paraphrased Virgil’s Aeneid:

As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the River Tiber foaming with much blood’.

Both Powell and Virgil used the blood theme to the same effect — describing conflict. But Powell turned the underlying meaning on its head, implying that multiculturalism and immigration would expose British citizens to violence. Virgil’s epic poem, however, foretold the harrowing journey the Trojans faced as war refugees.

Powell’s speech was contentious in its time and remains so. Virgil’s original allusions to blood contain far more violent imagery, yet they aren’t nearly as controversial. True, most of us have gotten over the Trojan War by now, but contrast also goes a long way. Gory rhetoric hits harder when it’s used out of context, and demagogues aren’t the only speakers who leverage the effect.

Winston Churchill and the Wartime Allusion

Powell’s address only used the word blood once. But he wasn’t the first politician to make a public statement that earned a bloody moniker despite its singular allusion to the idea.

In May 1940, Winston Churchill gave an inaugural address now known as the “Blood, Toil, Tears, and Sweat” speech. He announced to the House of Commons his intention to form a new government as Prime Minister, declaring:

I would say to the House, as I said to those who have joined this Government: ‘I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.’

In many speeches, blood takes on a literal meaning. This was also true during the Second World War, but Churchill’s hyperbolic metaphor was a masterful stroke. After decades of national service, he clearly had more to offer than just “blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” But downplaying his prior decades of achievements — and recent resignation as First Lord of the Admiralty — reinforced his image as an effective military leader.

These blood metaphors also stood out against Churchill’s Axis-power contemporaries. Hitler, for instance, invoked the idea of blood as a reflection of ethnic and racial identity. invoking the 18th-century slogan “Blut und Boden” (blood and soil) to mystically tie Nazism to nature while pursuing policies rooted in the destruction of foreign lands and societies. Mussolini used it to justify violence as a national calling, claiming: “It is blood which moves the wheels of history.”

With that said, Churchill’s oratorical canon wasn’t free of imperialistic ideas. He deemed Islam a religion of “blood and war” compared to Christianity as a religion of peace. He also stated that the collapse of the British Empire would be worse than bloodshed. Churchill appreciated the power of the blood allusion and as a skilled speaker, he was flexible with it.

The Countercultural Angle

Blood allusions aren’t bound to a single ideology or meaning, and their appeal defies language, time, and place. Many countercultural speakers use this to their advantage.

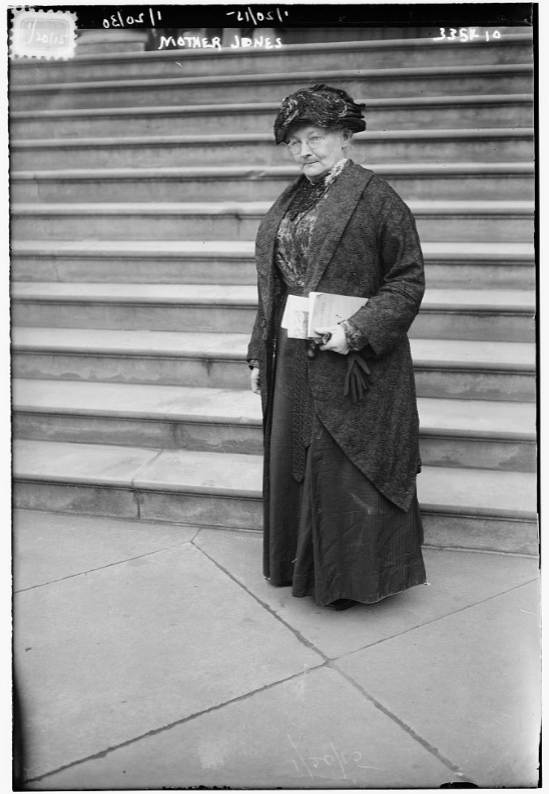

Mother Jones vs. the Bloodsuckers

In 1912, Irish-American labor organizer Mary Harris Jones — also known as Mother Jones or the most dangerous woman in America — spoke at a public meeting outside the capitol building in Charleston, West Virginia. Jones wasn’t averse to getting gory — she once described a bloody miner’s strike so well that labor leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn fainted. But for her Charleston address, she took a different approach.

Apart from briefly mentioning two instances of violence against labor activists, Jones avoided literalism. Instead, she peppered her speech with pejoratives, calling the anti-strikers “blood-hounds,” “blood-sucking pirates,” and “bloody murderers.” The crowd loved the metaphors, applauding and cheering along.

Jones’s popularity helped, but this was about more than celebrity status. She knew how to play to her audience, and her scorn fit the theme of much of her work. The days of laissez-faire capitalism had given rise to a palpable public sentiment that tycoons were profiting off the backs of workers. The “blood-sucking” theme was effective in that context. Working-

class audiences didn’t have to make a big logical leap to see the connection.

Blood Can Separate Us or Bring Us Together

Of course, Jones wasn’t the only person to employ this type of powerful antagonistic language. But others did so to far less progressive effects than fighting for labor rights.

Many populist speakers use blood to turn their audiences against minority groups. For instance, since the Middle Ages, the Jewish diaspora has borne the brunt of sensational fabrications involving tropes like blood libel.

Blood libel is the unfounded antisemitic idea that Jewish people use blood in human sacrifices. This unsettlingly vivid imagery made a convenient theme for speakers who wanted to incite violence against Jews or exclude them from Christian spaces. In the modern area, various authoritarians have used similar playbooks in asserting that foreign cultures would “poison” national bloodlines.

But blood is also an impactful countercultural unifier. In December 1859, the abolitionist John Brown stood before a Virginia court. Before receiving his death sentence for his failed Harper’s Ferry raid, he gave a speech rejecting his guilty conviction on charges of treason, murder, insurrection, and inciting a slave rebellion. But Brown also defied the social mores of the day, declaring:

“Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life, for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and MINGLE MY BLOOD FURTHER WITH THE BLOOD OF MY CHILDREN, and with the blood of millions in this Slave country, whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, – I say; LET IT BE DONE.

To Brown, blood wasn’t some indelible racial dividing line. Unlike one-drop rules and other customs designed to separate, blood was a common thread. It was something that brought people together for a common noble purpose.

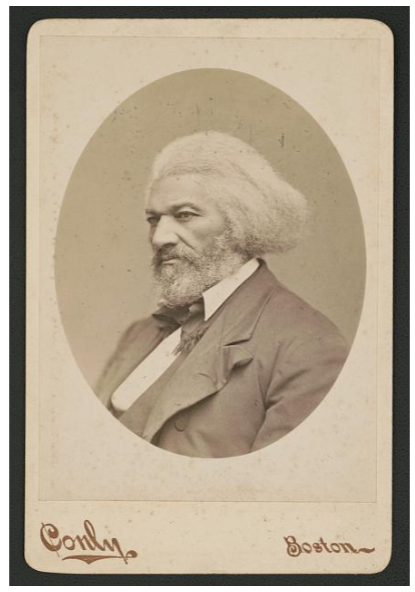

Other thinkers used blood as a unifier by condemning wrongdoing. In the summer of 1852, Frederick Douglass spoke to the people of Rochester, New York. That 4th of July celebration was a special one: the 76th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Douglass, however, used the occasion to speak out against the fact that not all Americans were free.

Douglass’s address, “What, to the slave is the Fourth of July?” castigated the American system as “shocking and bloody.” Unlike some abolitionists, he squarely placed blame on the citizens as economic supporters of the slave trade. He wasn’t addressing bloodied victims but rather those who bled their fellows, and he used words as weapons of motivation. He exhorted his listeners to live up to the American ideal, saying: “Your hands are full of blood; cease to do evil.”

Bloodstained Presidential Speeches

Oratory evolves — and so do its thematic underpinnings. We can see this in action by looking at speakers who all have something in common. Speeches and debates by US presidents are great sources, and the Miller Center makes 1,050 of these texts freely available to download.

Some caveats: This dataset doesn’t include every presidential speech or public remark in existence. Some transcripts also include asides from other speakers.

We’ve created an Observable notebook where you can play with the code and visualizations (you’ll need a browser that runs JavaScript). Here are a few highlights:

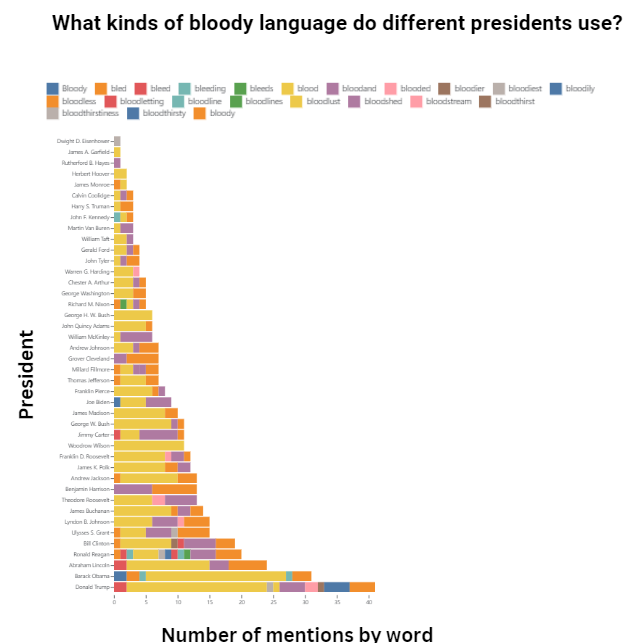

Blood Is a Popular Presidential Topic

- Of the 1,050 speeches in the dataset, 250 mentioned “blood”, “bleed”, “bled,” or variations of those terms.

- Out of 45 presidents, 42 mentioned blood in at least one of their speeches. John Adams, William Harrison, and Zachary Taylor bucked the trend.

- Many presidents couple the concept with ideas of nationality and geography — like “blood of American citizens” or “bloodshed in southern Africa”.

Some presidents seem to discuss blood more than others. Donald Trump, Barack Obama, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton used the most bloody allusions, despite these presidents’ relatively peaceful terms. Overall, Abraham Lincoln, James Buchanan, and Donald Trump mentioned blood in roughly 60%, 50%, and 49% of the speeches in the dataset.

Presidents Reference Blood in Their Own Styles

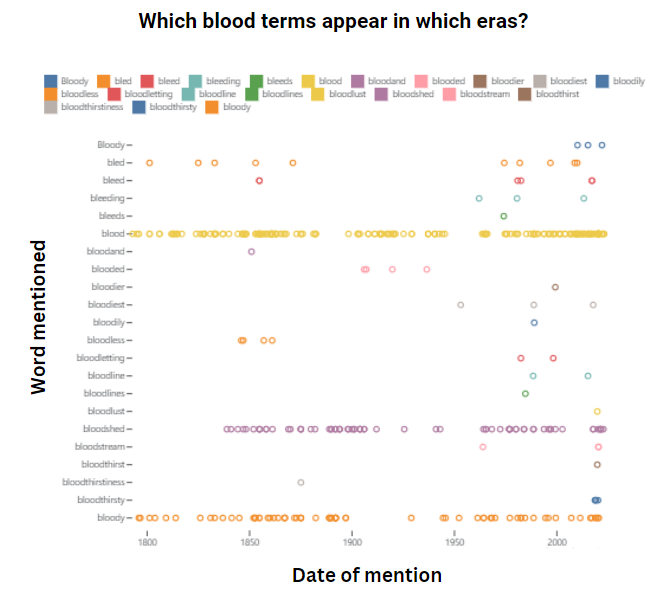

There doesn’t seem to be a standard Oval Office playbook for dealing with these topics. Presidents refer to blood in many ways, and in terms of linguistic diversity, Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump had the widest vocabularies.

Terms like “blood” and “bloody” are common. But when it comes to describing the act of bleeding, presidents seem to favor poetic idioms, and they’re not immune to cribbing from others, and they mostly stick with the times. For instance, George Washington, James Madison, Andrew Jackson, James Buchanan, and Franklin Pierce all used the phrase “effusion of blood.” This expression had been a popular way to describe violence since the Middle Ages, but it’s since become an almost exclusively medical term.

Artistic liberties aside, US leaders aren’t afraid to go for the proverbial jugular. Notable examples include Obama’s “gush of blood and splintered bone” and multiple presidents’ allusions to “river(s) of blood.”

Unpacking the Allusion

Speakers who use bloody ideas aren’t hucksters appealing to the lowest common denominator. They’re well-read, educated people who draw inspiration from the literary luminaries of history.

Blood has always been a strong dynamic theme in prose and poetry. William Shakespeare’s Macbeth used it as both a literal illustration of treacherous violence and a metaphor for guilt. Macbeth’s fixation with blood after murdering King Duncan suggests cowardice to his wife, the queen. Yet her madness eventually brings her visions of bloody hands she can’t wash clean.

Blood-inspired thematic ties also echo through modern literature. In Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, the main character, Okonkwo, seeks to distinguish himself from his deceased father, whose blood phobia is deemed a sign of cowardice.

Like Macbeth, Okonkwo is a flawed leader, given to violence, nightmares, and depression while resisting the British colonization of Nigeria. Achebe also carries the blood motif to the environment, drawing on W. B. Yeats’s 1919 poem The Second Coming. Not only is the title of Achebe’s work an homage to the poem, but the narrative also evokes the verse’s

“blood-dimmed tides.” When the colonizers kill a local clan, their sacred lake turns red.

At the end of the day, bloody public discourse might just be self-perpetuating. As long as the theme runs strong in other forms of art and literature, it’ll continue to define speechcraft. After all, audiences latch on to strong cultural themes, and wise orators ride the spirit of the times. When that spirit is steeped in blood, they’ve got ample leeway to flex their verbal prowess in their own sanguine style.

About the Author

AHJ George is a writer and painter who lives in the Californian desert. You can see more of their work on Contra.