For Healthcare Providers

Have your patient scan this QR code with their smartphone camera to instantly access this educational guide on their device.

A guide for patients with naturally lower neutrophil count

Access the Resources

Note: The video and audio linked above were generated with the assistance of AI. Clinical accuracy has been reviewed, but no AI-generated content can be guaranteed to be fully error-free.

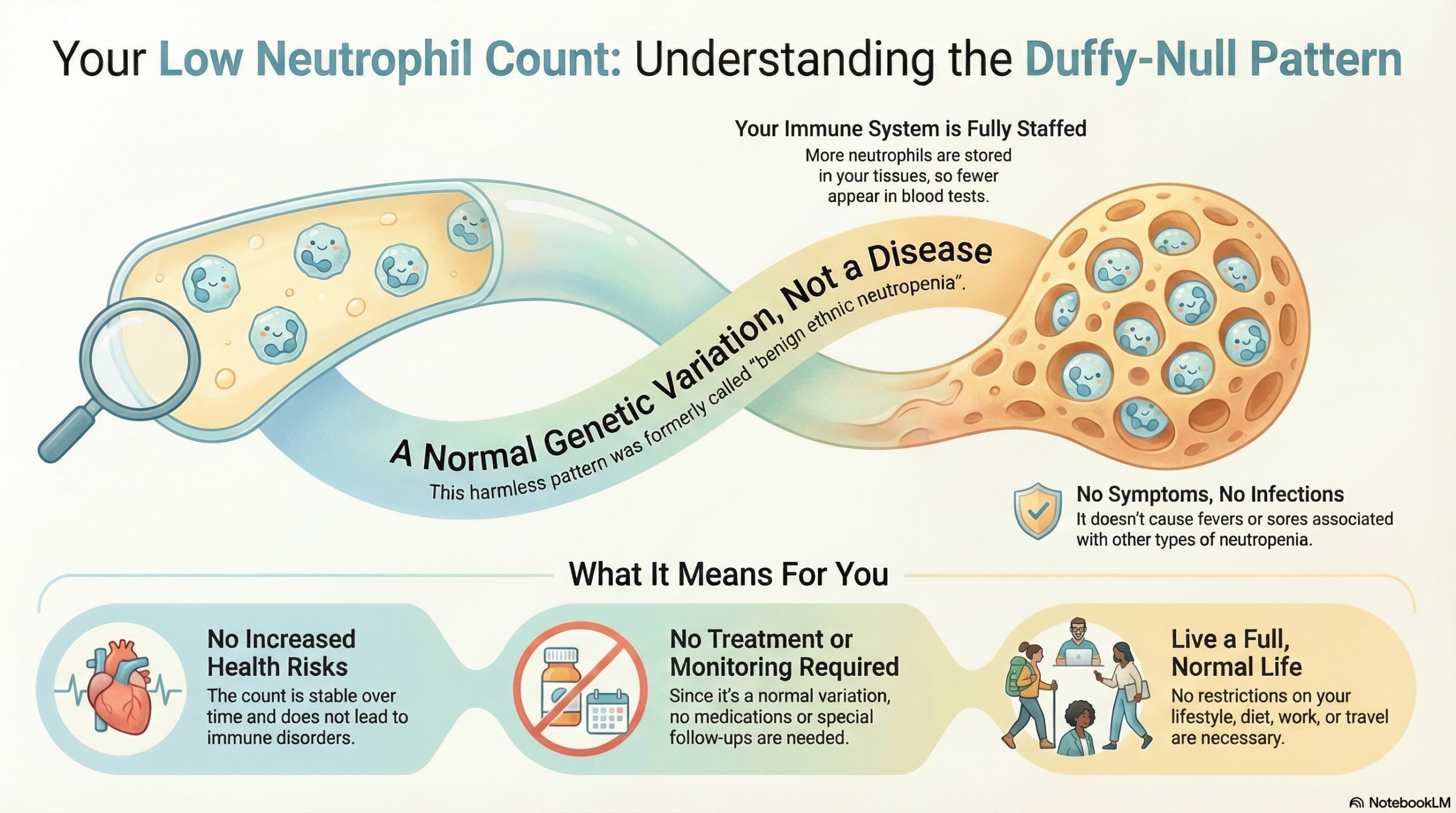

A lower neutrophil count can be concerning when it is caused by illness, medications, or bone marrow problems. However, many people have a naturally lower neutrophil count due to a common genetic pattern called the Duffy-null neutrophil count pattern.

This reflects how the body normally distributes neutrophils between the bloodstream and tissues. People with this pattern are healthy, have normal immune function, and do not have an increased risk of infection.

This pattern was previously called “benign ethnic neutropenia,” a term now discouraged because it inaccurately linked a normal biological variation to ethnicity rather than genetics.

First things first

A low neutrophil count can be concerning when it is caused by illness, medications, autoimmune disease, or bone marrow problems. In those situations, neutropenia can increase the risk of infection and needs careful evaluation.

The Duffy-null neutrophil count pattern is different. It reflects a normal genetic variation in how neutrophils are distributed between the bloodstream and tissues. People with this pattern are healthy, and their lower neutrophil count does not increase infection risk.

The most important goal is recognizing this as your normal baseline, so it is not mistaken for a medical problem that requires treatment or restrictions.

What is the Duffy-null neutrophil count pattern?

The Duffy-null pattern occurs when a person inherits two copies of a common genetic variant that affects the Duffy antigen on red blood cells. This variation influences how neutrophils circulate and where they spend their time in the body.

Because more neutrophils remain in tissues, fewer are seen in the bloodstream during a blood test, making the neutrophil count appear lower.

This is a normal genetic pattern, not a disease. It does not reflect bone marrow failure, immune deficiency, or impaired infection defense.

Why it happens (causes)

The Duffy-null pattern is inherited and present from birth. The genetic variant affects how neutrophils move between blood and tissues, not how well they are made or how well they function.

This pattern is common worldwide and is especially frequent in people whose ancestors lived in regions where malaria was historically prevalent, where the Duffy-null variant may have offered protection against certain malaria parasites.

Importantly, the immune system functions normally. Neutrophils are available and respond appropriately when needed.

Does it cause symptoms?

No. The Duffy-null neutrophil count pattern does not cause symptoms.

People with this pattern do not have frequent infections, mouth sores, slow healing, or other problems seen with true neutropenia. Most people discover this pattern only after routine blood testing.

Is it dangerous?

No. This pattern is not associated with increased infection risk or long-term health problems.

The neutrophil count typically stays in a stable, low-normal range over time. When the body needs more neutrophils, such as during infection or physical stress, neutrophils move into the bloodstream as expected and the count rises appropriately.

The baseline number is lower, but the immune response works normally.

How your doctor evaluates it

Your doctor looks at the overall pattern rather than a single number, including:

- whether your neutrophil count has been consistently low but stable

- whether other blood counts (red cells, platelets, other white cells) are normal

- whether you have symptoms of infection or immune problems

- your medical and family history

If you feel well and your neutrophil count is stable over time, this supports a Duffy-null pattern. Once recognized, no bone marrow testing or special follow-up is usually needed unless something changes.

Many people choose to keep a note in their medical record explaining their naturally lower baseline so that unfamiliar providers understand this finding.

How is it treated

No treatment is needed. This pattern reflects a normal variation, not a condition that requires correction.

You do not need medications, growth factors, antibiotics for prevention, supplements, or special monitoring.

Daily life and self-care

People with the Duffy-null pattern can live fully normal lives. No changes in activity, work, school, diet, exercise, or travel are required.

Blood donation eligibility varies by region, but many blood centers accept healthy donors with stable, naturally lower neutrophil counts.

If questions arise about genetics or family members, your doctor can help guide you.

What is the usual plan going forward?

No special plan is needed beyond routine medical care.

If your neutrophil count remains stable and you feel well, nothing further needs to be done. If the count changes significantly or symptoms develop, your doctor will reassess for other causes, just as they would in someone without this pattern.

Making sense of it

Think of neutrophils as workers who spend more time in the field than at headquarters. A blood test only counts who is at headquarters at that moment.

Because more of your neutrophils are already where they do their work, fewer are counted in the blood sample. The workforce is still complete, responsive, and effective.

Key takeaways

- a normal genetic pattern: your neutrophil count is naturally lower but healthy

- not a disease: it does not increase infection risk or require treatment

- stable over time: your count usually stays in a steady, low-normal range

- immune system works normally: neutrophils respond when needed

- no lifestyle restrictions: you can live, work, exercise, and travel normally

For clinicians: Read our detailed guide on how to communicate about DANC to patients.