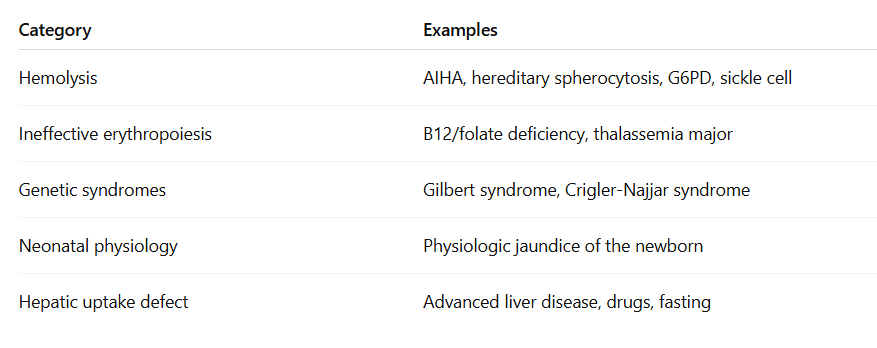

Introduction to Bilirubin Metabolism

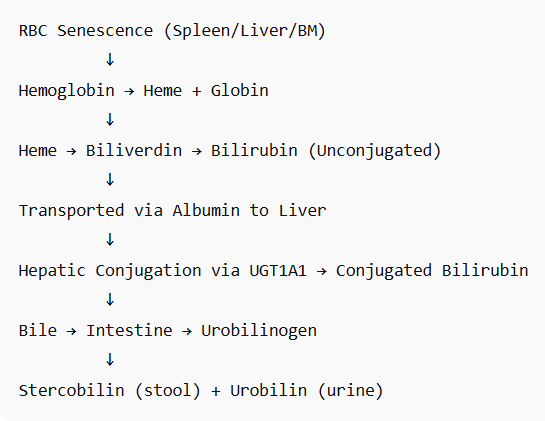

Bilirubin metabolism is the final step in the life cycle of red blood cells and a key process in the body’s handling of heme. Every day, billions of senescent red blood cells are broken down by macrophages, releasing hemoglobin, which is further metabolized into bilirubin. This bilirubin is initially unconjugated and must undergo a series of well-orchestrated steps involving hepatic uptake, enzymatic conjugation, and biliary excretion before it is ultimately eliminated from the body. Understanding this pathway is essential for interpreting abnormal bilirubin levels and diagnosing conditions such as hemolysis, liver dysfunction, and inherited disorders like Gilbert syndrome.

For larger image, click here.

- Red blood cell senescence and destruction:

- RBCs circulate for about 120 days.

- About 1% of the body’s RBCs (roughly 200 billion) are removed from circulation daily.

- Senescent RBCs are phagocytosed by macrophages in the spleen, liver (Kupffer cells), and bone marrow—components of the reticuloendothelial system (RES).

- Hemoglobin breakdown:

- Each RBC contains hemoglobin (Hb),1 which is broken down into:

- Globin → degraded into amino acids (reused)

- Heme → further metabolized into:2

- Iron (Fe²⁺) → stored as ferritin or hemosiderin or recycled for new RBC synthesis

- Protoporphyrin ring → converted to biliverdin by the enzyme heme oxygenase3

- Biliverdin → reduced to unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin by biliverdin reductase4

- Each RBC contains hemoglobin (Hb),1 which is broken down into:

- Unconjugated bilirubin in plasma:

- Unconjugated bilirubin is lipophilic and water-insoluble.

- It is transported in blood bound to albumin.

- This form is also called indirect bilirubin (measured on labs).

- Hepatic uptake and conjugation:

- Hepatocytes in the liver take up bilirubin from plasma via passive diffusion and facilitated transport..

- Inside the hepatocyte:

- UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A1) conjugates bilirubin with glucuronic acid (adds one or two glucuronic acid residues), forming conjugated (direct) bilirubin, which is water-soluble.

- Biliary excretion:

- Conjugated bilirubin is secreted into bile canaliculi, then into the biliary tract, and ultimately into the duodenum via the common bile duct.

- Intestinal metabolism (not shown in above graphic):

- In the gut, bacterial enzymes deconjugate bilirubin and convert it into:

- Urobilinogen, which has several fates:

- Some is reabsorbed into the portal circulation (enterohepatic circulation)

- A small amount is excreted in urine as urobilin (yellow pigment)

- Most is converted to stercobilin and excreted in feces (brown pigment)

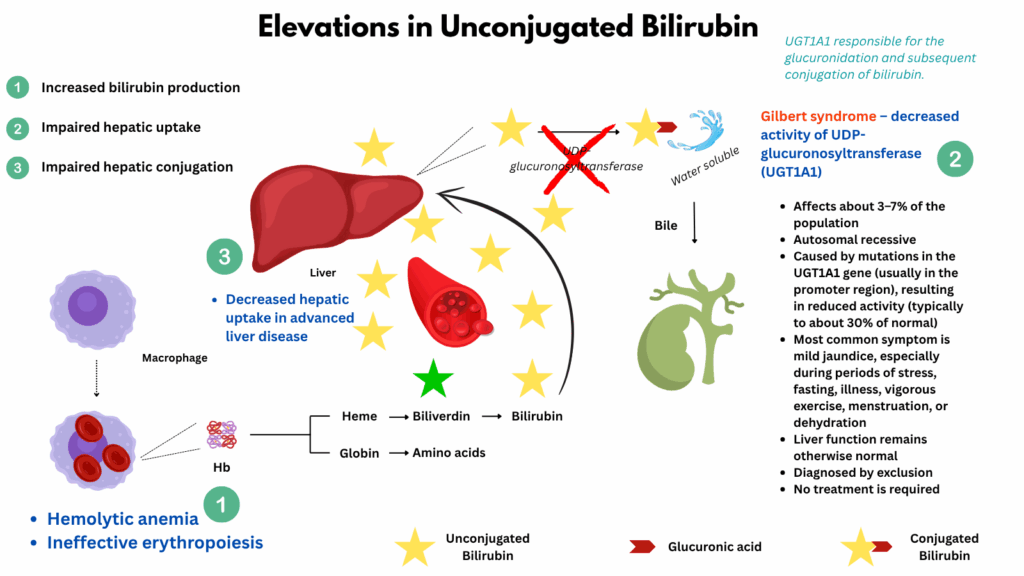

Indirect hyperbilirubinemia

Indirect (unconjugated) hyperbilirubinemia occurs when there is an excess of bilirubin in the bloodstream before it has been processed by the liver. This can result from increased production (as in hemolysis or ineffective erythropoiesis), impaired hepatic uptake, or decreased conjugation (as in Gilbert syndrome). Because unconjugated bilirubin is not water-soluble, it does not appear in the urine and must be evaluated in the context of hemolytic and hepatic function.

Note about bilirubin levels: Values for total bilirubin above 2.0–3.0 mg/dL often result in visible jaundice, and indirect bilirubin above 1.3 mg/dL is generally considered elevated for adults. In clinical situations, indirect bilirubin can rise above 2 mg/dL (sometimes reported as high as 8–10 mg/dL or more in severe hemolysis or genetic disorders). In newborns, indirect (unconjugated) bilirubin can sometimes rise to dangerous levels above 15–20 mg/dL. Extremely high levels (e.g., over 20 mg/dL in adults) are rare and typically associated with severe hemolytic anemia, genetic disorders (like Crigler-Najjar or Gilbert syndrome), or significant liver dysfunction.

For larger image, click here.

The major causes fall into three broad categories:

- Increased bilirubin production (hemolysis or ineffective erythropoiesis):

- Hemolytic anemias (intravascular or extravascular)

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA)

- Hereditary spherocytosis, elliptocytosis

- G6PD deficiency

- Sickle cell disease

- Thalassemia

- Ineffective erythropoiesis

- Vitamin B12 or folate deficiency (megaloblastic anemia)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes

- Thalassemia major

- Hemolytic anemias (intravascular or extravascular)

- Impaired hepatic uptake:

- Gilbert syndrome – decreased activity of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A1); very common, benign

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome – congenital absence (type I) or severe reduction (type II) of UGT1A1

- Neonatal jaundice – immature UGT system in newborns

- Impaired hepatic conjugation

- Advanced liver disease may impair bilirubin uptake or conjugation