Blood’s association with love and sex may seem tenuous, or else Sadean, upon first consideration. Yet blood plays a fundamental role in almost all bodily expressions of stimulation, arousal, climax and fertility. By the same token, one does not need to look far to deduce the link between love and blood. Though we may hold widely differing definitions of love, the heart—the very symbol which we most frequently employ to express love—also happens to be responsible for the blood’s flow through- out our bodies.

Even our first encounter with fornication has been historically tied to blood. In many cultures, the virginity of a bride-to-be is highly preferred, or even a prerequisite. Among some, it has even been expected of a newly-wed bride to prove her celibacy up to that point by displaying the bed sheet upon which her marriage had been consummated; the idea being that a true virgin’s hymen would have broken and bled upon her first sexual experience. Conflation of the hymen and virginity, however, has largely been dismantled in recent years due to developments in our understanding of this particular membrane.

In other parts of the world, blood is an important part of courtship. In East Asian culture particularly, a potential partner’s blood type can be a key factor in determin- ing compatibility. Although modern scientific communities are dismissive of blood type personality theories, they have done little to dampen the support for the idea, especially in Japan. The notion that personality traits are predetermined by bodily fluids, however, dates as far back as Ancient Grecian times, when variances in tem- perament and issues in health were attributed to imbalances in the four humours: black bile, yellow bile, phlegm and blood. To this day, many of our words and idioms tie blood and sentiment together, including the adjectives “sanguine”, denoting exces- sive optimism; “red-blooded”, signifying vigorous or virile; “cold-blooded”, meaning void of emotion; and “hot-blooded”, denoting a person’s excitability or passion.

Blood as a determinant of romantic compatibility is a multifaceted and often con- troversial concept, particularly when it concerns consanguineous relationships, ones wherein both partners are blood-related. In a majority of countries, consanguine- ous romantic unions are discouraged. However, for around one-fifth of the world’s population—particularly in the Middle East, West Asia and North Africa—consan- guinity is the cultural norm. The arguments opposing consanguineous unions are primarily founded on increasing awareness of the higher probability of congenital and genetic disorders being passed on to offspring. Despite this, around one billion people worldwide live within communities that support consanguineous marriages, and Europe is no stranger to it. Many members of the royal families of Europe, including my very monarch, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, have married within their own bloodlines.

It is not only the romantic or erotic shades of love which are coloured by blood. Notions of parental love have deep biological roots in blood. The first moments of parenthood are most often heralded by the temporary pause of a woman’s menstrual cycle, which itself remains widely stigmatised today, despite play- ing a key role in the regulation of female fertility. Throughout pregnancy, the umbilical cord—containing two arteries and one vein—supplies the unborn child with oxygenated, nutrient-rich blood from mother to child through the placenta. Childbirth too is a crimson affair, with an average of half a litre of blood lost during each labour and delivery.

As a child, I possessed a profound curiosity about the human body; a curiosity which in many respects persists today, but one which would surely have perished were it not for my mother. In an effort to nourish my intrigue, each fortnight my mother would purchase a single tome of a collection of books which explained every rudimentary feature of the human anatomy: every organ, every tissue, every system; I learnt the names of every bone and muscle. One tome I was particularly curious to obtain was the one explain- ing the genitalia. Even from that young age of five or six, I had an insatia- ble spirit of enquiry for the body, particularly the male body, particularly my own. I wanted to understand its hydraulics and hormones. I yearned to know its hows. The tome on the “reproductive system” did not disappoint. Half of the tome was dedicated to the anatomy and purposes of the scro- tum, testes, penis and foreskin. Everything from erections to orgasm was thoroughly covered, and what struck me most was the important role blood played in these functions.

As my literary tastes matured beyond the basics of biology, blood con- tinued to flow in tandem with sex and love in the titles of my adolescence. In Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), the eponymous protagonist’s bloodlust and sexuality frequently intersect. From the vampiric act of penetrating (albeit with fangs), to the drawing of blood (a metaphor for other bodily fluids), much of Stoker’s novel is rife with sexualised bloody imagery. In chapter 10, one line reads, “No man knows till he experiences it, what it is like to feel his own life-blood drawn away into the woman he loves.”

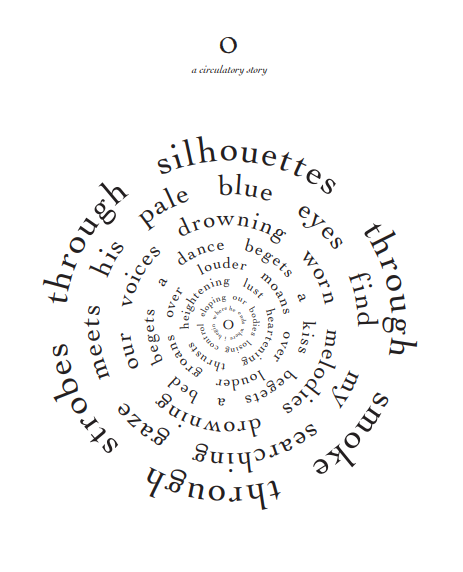

In a more romantic vein, some of the world’s most revered wordsmiths turned to blood as metaphors for love and affection. In a letter sent to his lover, Véra, on November 8th, 1923, Vladimir Nabokov penned the line, “I am ready to give you all of my blood, if I had to.” Also, in one of the Russian writer’s diaries in which he recorded his dreams, the entry for 13th December 1964 reads: “Intensely erotic dream. Blood on sheet.” A little closer to home are Shakespeare’s sonnets. Although blood imagery spatters a sparse number of the sonnets, such as XIX and CXXI, the iambic cadence of a heartbeat throbs plentifully throughout his poetry.

Excerpt of Visceral by RJ Arkhipov, republished with permission of the author and Zuleika.

About the Author

RJ Arkhipov was born in Wales. Reborn in Paris. He moved to the French capital at the age of eighteen to study French literature, cinema, and art history at the University of London Institute in Paris. RJ gained international acclaim when he penned a series of poems using his own blood as ink to protest the gay blood donor ban in the United Kingdom, United States, and much of Europe. Today living in Edinburgh, Scotland, Arkhipov’s first collection of poetry—Visceral: The Poetry of Blood—explores the male body and the contemporary gay experience, with a particular focus on stigma and sensuality.