Postscript

Prev

1 / 0 Next

Prev

1 / 0 Next

Bottom line

- Smoking is associated with leukocytosis.

- As a general rule the increase in white blood cell count (WBC) is modest (<20%), with the total WBC count rarely exceeding 20 x 109/L.

- All WBC subtypes are affected, but the predominant effect is on neutrophils.

- There is a dose response such that WBC counts are higher in heavy vs. lighter smokers.

- Smoking cessation leads to a time-dependent reversal of leukocytosis, though there is a still a residual effect years after stopping.

Introduction

- Leukocytosis is defined as an elevated total white blood cell count (> 11 x 109/L).

- Leukocytosis is a laboratory finding commonly detected on routine peripheral blood analysis.

- Tobacco smoking is a recognized cause of leukocytosis.

History

- The association between smoking and leukocytosis was first described by Howell in 1971. In one short sentence, he wrote: “The table shows mean erythrocyte sedimentation-rates (E.S.R.) about 10% higher in cigarette smokers than in non-smokers, but the most striking difference is between mean white-blood-cell counts in heavy smokers and in non-smokers.”

Mechanisms

- The precise mechanisms by which cigarette smoke leads to an elevation in white blood cell (WBC) levels are unclear.

- Possible mechanisms include:

- Components of cigarette smoke causing:

- Chronic systemic inflammatory response (mediated in part by changes in cytokine levels, especially IL-6)

- Direct injury of epithelial and endothelial surfaces.

- Impaired function of alveolar macrophages, leading to decreased clearance of intracellular apoptotic material and likely propagating inflammation.

- Shortened transit time of polymorphonuclear leukocytes within the bone marrow.

- Nicotine causing:

- Release of catecholamines.

- Increased production cortisol.

- Components of cigarette smoke causing:

Cohorts

- Cohort (1971) of 4264 men from a large section of the Paris Civil Service:

- The white blood cell count (WBC) was determined utilizing a Fisher autocytometer on a venous blood sample.

- The average number of WBCs was higher in smokers than in non-smokers and much higher in smokers who inhaled than in those who do not.

- The average number of WBCs was greater in smokers who inhale than in those who did not, whatever the amount smoked; the heavier the smoker, the greater the difference.

- Analysis of a second cohort of 483 individuals showed that all subtypes of WBCs were increased, with relative increase of:

- 24% in granulocytes

- 15% in lymphocytes

- 22% in monocytes

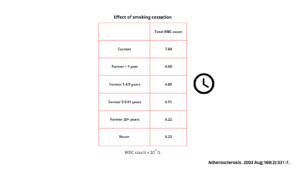

- Cross-sectional population-based study (2003) of 6902 men and 8405 women 39-79 years of age from the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer (EPIC-Norfolk) study:

- Mean total white blood cell (WBC) counts about 20-25% higher in smokers than non smokers.

- Difference in mean total WBC count:

- 1.6 x 109/L in men

- 1.2 x 109/L in women

- The crude and age- and body mass index-adjusted mean total WBC, lymphocyte, granulocyte and monocyte counts were highest among current smokers followed by former and then never smokers in both sexes.

- While differences were apparent for all WBC subsets, the greatest absolute and percentage differences were observed for the granulocyte count.

- Total WBC, granulocyte and lymphocyte counts (adjusted for age and body mass index):

- Correlated with cumulative exposure to smoking.

- Declined with increasing number of years since giving up smoking towards the values observed in never smokers.

- A sharp decline in all mean total blood cell counts was observed within less than 1 year of reported smoking cessation in both sexes.

- The authors concluded: “Our data indicate a strong association between the mean total WBC count and its components (particularly the granulocyte count) and cigarette smoking habit.”

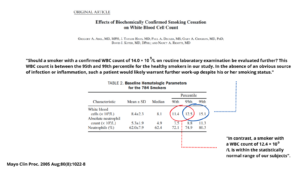

- Cohort (2005) of 784 healthy smokers:

-

- 461 had biochemically confirmed tobacco abstinence after 7 weeks of bupropion.

- Of these 461 subjects, 429 were randomized to receive either continued bupropion therapy (n=214) or placebo (n=215) until week 52.

- At baseline:

- The mean ± SD white blood cell (WBC) count was 8.4±2.3 × 109/L.

- The mean ± SD absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was 5.3±1.9 ×109/L.

- The 90th percentile for the WBC count was 11.4 ×109/L.

- The 90th percentile for the ANC was 7.5 ×109/L.

- Between baseline and week 7, there was a significantly larger decrease in WBC count in continuously abstinent subjects compared with continuing smokers.

- At 52 weeks, continuously abstinent subjects, compared with continuing smokers, had a greater decline from baseline in WBC count.

- The authors concluded: “Biochemically confirmed tobacco abstinence leads to a rapid and sustained decrease in WBC and ANC, possibly reflecting a decrease in an underlying state of tobacco-induced inflammation”.

-

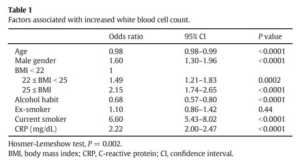

- Cross-sectional study (2016) of 37,972 healthy Japanese adults and longitudinal study involving 1730 current smokers:

- Elevated white blood cell (WBC) count was associated with:

- Younger age

- Male gender

- Increased body mass index

- No alcohol habit

- Current smoking

- Elevated C-reactive protein level were associated with

- Among these factors, current smoking had the most significant association with elevated WBC count.

- Elevated white blood cell (WBC) count was associated with:

-

- In subgroup analyses by WBC differentials, smoking was significantly associated with elevated counts of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils.

- In the longitudinal study of 1730 individuals who were current smokers at their first visits:

- 231 individuals quit smoking within one year after the first visit and remained abstinent for the next 4 years

- Significant decrease in WBC count (mean, 5.374 × 109/L) from baseline (mean 5.642 × ×109/L).

- The decrease in WBC count remained significant compared to the baseline level for the next two years.

- 1499 smokers continued smoking for longer than four years after the first visit:

- The mean WBC counts of the continuing smokers did not change either one year after the first visit (mean 6.087 × 109/L) or two years afterward (mean 6.059 × 109/L) from baseline (6.031 × 109/L.

- 231 individuals quit smoking within one year after the first visit and remained abstinent for the next 4 years

- Both WBC and neutrophil counts decreased significantly in one year after smoking cessation and remained down-regulated for longer than next two years.

- There was no significant change in either WBC or neutrophil count in those who continued smoking.

- The authors concluded: “These findings clearly demonstrated that current smoking is strongly associated with elevated WBC count and smoking cessation leads to recovery of WBC count in one year, which is maintained for longer than subsequent two years. Thus, current smoking is a significant and reversible cause of elevated WBC count in healthy adults.”

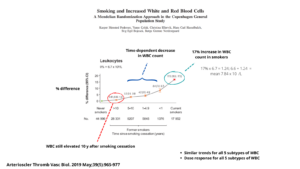

- Cohort (2019) of 104,607 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study:

- Of the cohort:

- 44,996 were never smokers.

- 41,759 were former smokers.

- 17,852 were current smokers.

- Compared with never-smokers, being a former and current smoker was associated with having increased white blood cell (WBC) counts, including all the different subpopulations, despite adjustment for potential confounders.

- White blood cell counts were increased:

- 14% to 19% in current smokers.

- 0.6% to 15% in former smokers depending on time since smoking cessation:

- Those with >10 years since smoking cessation had the lowest increases.

- Those with <1 year since smoking cessation had the highest increases.

- In current smokers, higher cumulative and daily tobacco consumption was associated with having higher increases of WBC counts in a dose-dependent manner despite adjustment for potential confounders.

- Of the cohort:

- Cohort (2020) of 11,083 individuals from the Danish General Suburban Population Study:

- Compared to never smokers, white blood cell (WBC) counts were increased in current smokers, ex-smokers and ever smokers.

- Results were similar for all WBC subpopulations (including neutrophils, eosinophils, monocytes and lymphocytes), except for neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and basophils.

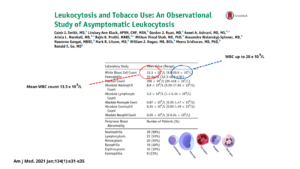

- Observational study (2021) of forty patients with smoking-induced leukocytosis:

- The mean white blood cell (WBC) count was 13.3 x 109/L (range: 9.8-20.9 x 109/L):

- 39 (98%) had absolute neutrophilia [Authors stated: “The predominance of neutrophilia within this study is in line with prior investigations”]

- 21 (53%) had lymphocytosis.

- 20 (50%) had monocytosis.

- 19 (48%) had basophilia. [Authors noted: “Interestingly, almost half of patients in this study had basophilia”]

- During follow-up, 11 patients either quit (n = 9) or reduced (n = 2) tobacco use. Reduction in

tobacco smoking led to a significant decrease in mean WBC count (13.2 x 109/L vs 11.1 x 109/L, P = 0.02). The median time to decrease in white blood cell count following reduction in tobacco use was 8 weeks (range: 2-49 weeks). - Of the patients who reduced their tobacco use, 91% experienced improvement in leukocytosis.

- The authors concluded: “Tobacco-induced leukocytosis was characterized by a mild elevation in total white blood cell count and was most commonly associated with neutrophilia, lymphocytosis, monocytosis, and basophilia. Cessation of smoking led to improvement in leukocytosis. Tobacco history should be elicited from

all patients presenting with leukocytosis to limit unnecessary diagnostic testing, and counseling regarding

smoking cessation should be offered”.

- The mean white blood cell (WBC) count was 13.3 x 109/L (range: 9.8-20.9 x 109/L):

Prev

1 / 0 Next