About the Condition

Prev

1 / 0 Next

Prev

1 / 0 Next

Introduction

- Babesiosis (also known as Nantucket fever) refers to a vector-borne zoonosis caused by intraerythrocytic protozoa of the genus Babesia that are transmitted by hard-bodied ticks, or less commonly through blood transfusion or across the placenta (vertical transmission).

- Babesia species:

- Belong to the phylum Apicomplexa, which is comprised of several important human pathogens, such as species of:

- Plasmodium

- Toxoplasma

- Cryptosporidium

- Divide and replicate in the red blood cells (RBCs) of diverse vertebrate hosts.

- Belong to the phylum Apicomplexa, which is comprised of several important human pathogens, such as species of:

- Over 100 Babesia species infect a wide variety of wild and domestic animals. Humans are an accidental host.

- A subset of Babesia species infect humans, including:

- In the US:

- Babesia microti:

- Endemic in the Northeast and upper Midwest.

- The most common cause of human babesiosis.

- Babesia duncani

- Babesia divergens

- Babesia microti:

- In Europe:

- B. divergens

- B. microti

- Babesia venatorum

- In Asia:

- B. venatorum

- B. microti

- Babesia crassa-like pathogen

- In the US:

- Babesia is an obligate intracellular parasite.

- The primary vector (mode of transmission) of human babesiosis is Ixodes ticks (Ixodes scapularis, also known as the deer tick or blacklegged tick), which feed on competent natural hosts, including rodents and cattle, and also transmit:

- Borrelia burgdorferi (the etiologic agent of Lyme disease)

- Anaplasma phagocytophilum

- Borrelia miyamotoi

- Ehrlichman muris–like agent

- Powassan virus

- The primary natural reservoir for B microti in the northeastern and upper midwestern United States is the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopins).

- History:

- 1888 – Viktor Babes first described the parasite using blood smears from Romanian cattle with fever and hemoglobinuria.

- 1893 – Smith and Kilbourne of the US Bureau of Animal Industry identified ticks as the mode of transmission in Texas cattle.

- 1957 – the first human case was described by Skrabalo and Deanovic in Yugoslavia, a splenectomized Yugoslavian herdsmen died of infection with B. divergens.

- 1968 – Babesiosis was first documented in the United States in a splenectomized California resident.

Epidemiology

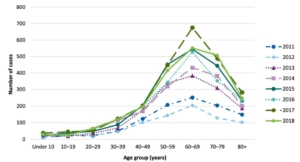

- Human babesiosis has been nationally reportable to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since 2011.

- More than 2000 cases of babesiosis are reported each year to the CDC, and the incidence is increasing owing to:

- Increase in the white-tailed deer/Ixodes scapularis tick populations.

- Enhanced clinical awareness and increased recognition of the disease.

- Increased human exposure to B. microti-infected ticks owing to rural development.

- Increased geographic range of ticks carrying B. microti.

- Increasingly immunosuppressed population.

- Increasing number of travelers.

- Aging population

- Increasing number of blood transfusions.

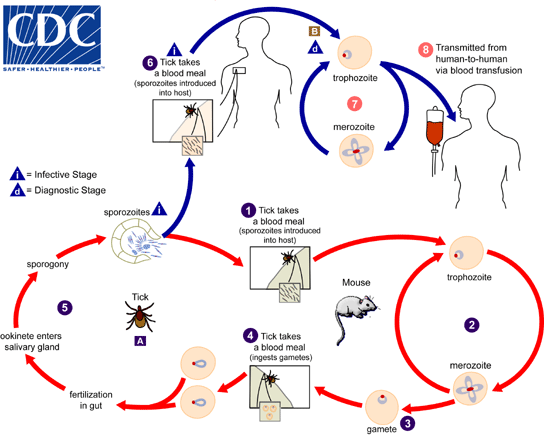

- Babesiosis is a zoonotic disease with an enzootic cycle between a tick vector and vertebrate hosts.

- Humans are accidental hosts and most commonly acquire infection through the bite of an infected tick, with the risk of infection being greatest in late spring and summer, when the population of infected ticks attempting to feed is at

its greatest and in areas where the tick vector, vertebrate reservoirs, and deer are in close proximity to humans. - Transmission:

- Primarily during the bite of an I. scapularis tick.

- Rarely through:

- Blood transfusion:

- The incidence of transfusion-transmitted Babesia has been reported to be about 1.1 cases per million packed RBCs across the United States.

- Organ transplantation

- Vertical transmission, resulting in congenital babesiosis.

- Blood transfusion:

- In endemic areas:

- The prevalence of B microti infection in nymphal I scapularis ticks ranges between 1%-20%.

- Up to two-thirds of white-footed mice harbor B. microti in areas in which the pathogen is endemic.

- Most cases worldwide have been those caused by B. microti from the northeastern and northern midwestern regions of the United States where babesiosis is endemic:

- Ninety-five percent of cases in the US are in the Northeast and Upper Midwest, but cases have been reported in almost every state. Infections occur primarily in seven states, including MA, CT, RI, NY, NJ, MN and WI.

Increasing incidence of babesiosis over recent years. Pathogens. 2021 Nov 6;10(11):1447.

Pathogenesis

- Most Babesia spp. are small (1–5 mm in length) and appear pear-shaped, round, or oval.

- Babesia microti has a two-host life cycle involving hard-bodied ticks of the genus Ixodes as the definitive host and a vertebrate intermediate host.

- When Babesia sporozoites are first injected via a tick bite into the human host:

- They invade host red blood cells (these are their only target host cell) using poorly understood mechanisms (cognate receptor-ligand pairs have not yet been identified).

- Sporozoites quickly invade red blood cells (RBCs) and undergo asexual reproduction (called merogony)

- After attachment and entry into the red blood cell, babesia organisms mature into trophozoites that eventually undergo asexual budding to yield two or four daughter cells known as merozoites:

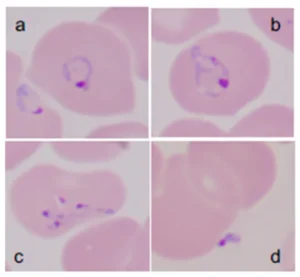

- In early stage of the cycle, they appear as ring stages.

- Asexual replication (budding or fission) gives rise to a parasite form commonly called the figure eight form.

- Division may occur again, giving ride to the tetrad form know as a Maltese Cross.

- Resulting daughter merozoites are then intermittently released (within 8 hours of infection) to infect new erythrocytes.

- The release of merozoites and eventual erythrocyte lysis is associated with the symptoms and complications of the infection, including hemolytic anemia, jaundice, hemoglobinemia, obstruction of renal arterioles, and renal insufficiency.

- Hematologic manifestations of Babesia are common in the human host:

- Thrombocytopenia is caused by

- Hypersplenism (the main mechanism)

- DIC

- Immune-mediated destruction of platelets

- Anemia is caused by:

- Hemolysis (main mechanism)

- Oxidative stress

- Rarely, patients exhibiting warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia postinfection have been described.

- Splenic complications of acute Babesia microti infection:

- Complications include:

- Splenomegaly:

- The spleen is an essential organ for the clearance of intraerythrocytic parasites such as Plasmodium spp. and Babesia spp.

- The splenic immune response and extramedullary erythropoiesis explain why patients who experience high-grade parasitemia tend to present with splenomegaly.

- Splenic infarct

- Splenic rupture

- Splenomegaly:

- Main mechanisms by which B. microti might cause splenic complications:1

- B. microti causes hemolysis by direct parasite invasion which leads to endothelial damage, formation of microthrombi, and release of vasoactive factors, resulting in localized necrosis of splenic tissue.

- Enhanced cytoadherence of RBCs can cause mechanical obstruction of splenic microcirculation leading to infarction and rupture.

- Splenic macrophages are crucial in the clearance of infection, and in the process of “removal” of infected erythrocytes trapped in its venules, the spleen enlarges and subsequently may rupture.

- Complications include:

- Thrombocytopenia is caused by

- Factors other than hemolysis contributing to clinical manifestations and complications include:

- Excessive proinflammatory cytokine production.

- Obstruction of blood vessels due to erythrocyte cytoadherence (little evidence).

Clinical manifestations

- Clinical manifestations of babesiosis range from asymptomatic infection to an influenza-like illness to severe disease with end-organ compromise and death.

- Asymptomatic infection:

- Asymptomatic B microti infection has been recorded in about a 20% of adults and 50% of children.

- Can persist for months-years.

- In New England, seroprevalence has varied between 0.5% and 16%.

- Greatest risk of asymptomatic infection is the ability to donate blood and contribute to transfusion-transmitted babesiosis.

- Mild to moderate infection:

- Incubation period of about:

- 1-4 weeks after a tick bite.

- 1 week to 6 months (usually 1-9 weeks) after blood transfusion.

- Gradual onset of malaise and fatigue is accompanied by fever and one or more of the following:

- Most common:

- Chills

- Sweats

- Anorexia

- Headache

- Myalgia

- Less common:

- Nausea

- Nonproductive cough

- Arthralgia

- Emotional liability and depression

- Hyperesthesia

- Neck stiffness

- Sore throat

- Abdominal pain

- Conjunctival injection

- Photophobia

- Weight loss

- Shortness of breath

- Most common:

- Physical exam may show:

- Fever

- Abdominal tenderness of the upper left quadrant suggests splenomegaly

- Splenomegaly

- In 88.5%-90% of cases

- Usually mild

- Hepatomegaly

- Pallor

- Pharyngeal erythema

- Jaundice

- Retinopathy with splinter hemorrhages and retinal infarcts

- expanding, erythematous skin lesion may be due to concurrent Lyme disease

- Labs may show:

- Hemolytic anemia

- Thrombocytopenia

- Lymphopenia (common)

- Neutropenia (less common)

- Elevated serum liver enzyme concentrations

- Symptoms usually resolve in a week or two but anemia and fatigue may persist for several months.

- Incubation period of about:

- Severe disease:

- Severe babesiosis requires hospital admission and usually occurs in patients who:

- Are > 50 years old

- Are immunocompromised:

- Splenectomy

- Malignancy

- HIV infection

- Immunosuppressive therapy

- Have comorbidities

- Experience infection with B. divergens

- Co-infection with Lyme disease

- Complications include:

- Adult respiratory distress syndrome

- Pulmonary edema

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Congestive heart failure

- Renal failure

- Coma

- Splenic complications

- Include:

- Splenic rupture

- Splenic infarct

- Unlike other severe complications of babesiosis, splenic infarct and rupture occur in younger and immunocompetent patients, and they do not correlate with parasitemia level.

- In a systematic review, splenic rupture was a more common complication of babesiosis than splenic infarct.2

- Include:

- Prolonged relapsing course of illness despite standard antibiotic therapy

- HLH

- Death occurs in up to 10% of patients hospitalized for B microti infection.

- Concurrent infection with B microti and one or several tick-transmitted pathogens can occur and may increase the number and duration of acute symptoms.

- Severe babesiosis requires hospital admission and usually occurs in patients who:

Diagnosis

- Babesiosis has no easily recognized clinical features such as the erythema migrans skin lesion of Lyme disease.

- Diagnosis of babesiosis is based on:

- Epidemiologic and medical history

- Physical examination

- Confirmatory laboratory tests

- Consider diagnosis of Babesiosis in anyone who has:

- Characteristic babesial symptoms, especially:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Chills

- Sweats

- Headache

- Anorexia

- Lived in or traveled to an endemic area in the late spring to early autumn:

- The pretest probability of babesiosis in a person who does not live in or has not traveled to an endemic area within the previous month is low, and testing for Babesia in such individuals is not warranted.

- Received a blood transfusion in the previous 6 months.

- Characteristic routine laboratory test abnormalities.

- Characteristic babesial symptoms, especially:

- Screening lab tests include:

- Complete blood count (CBC) that may show:

- Low hemoglobin and hematocrit

- Elevated reticulocyte count

- Low platelet count

- Lymphopenia

- Neutropenia (in around one-third of adults with this infection)3

- Hemolytic indices:

- Elevated serum LDH

- Elevated AST

- Low haptoglobin

- Elevated indirect bilirubin

- Liver enzymes:

- Elevated alkaline phosphatase

- Elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferases

- Elevated bilirubin

- Urinalysis may reveal:

- Hemoglobinuria

- Hematuria

- Excess urobilinogen

- Complete blood count (CBC) that may show:

- A diagnosis of babesiosis can be confirmed by microscopic detection of parasites within red blood cells on Giemsa-stained or Wright-stained thin blood smears:

- Rapid and inexpensive.

- Examination of multiple thin blood smear fields is indicated.

- Babesia organisms are small and may be missed on thick blood smears. Thin smears are preferred to thick smears for visualizing the organism.

- A review of at least 200–300 fields under oil immersion will increase sensitivity, although the number of fields has not been standardized.

- Findings include:

- Intraerythrocytic organisms, especially:

- Ring forms – smaller compared with malaria

- Tetrads (Maltese cross) – unique to babesiosis

- Exoerythrocytic organisms – not present in malaria.

- Intraerythrocytic organisms, especially:

- Levels of parasitemia may range from less than 1% to more than 80% of erythrocytes.

Giemsa-stained thin blood films showing Babesia microti parasites. B. microti are obligate parasites of erythrocytes. Trophozoites may appear as ring forms (A) or as ameboid forms (B). Merozoites can be arranged in tetrads and are pathognomonic (C). Extracellular parasites can be noted, particularly when the parasitemia level is high (D). Pathogens 2019, 8(3), 102.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR):

- A more sensitive diagnostic test than blood smear.

- If blood smears are negative and babesiosis is still suspected, PCR testing should be performed.

- Provides a molecular characterization of the Babesia species.

- Especially useful when the parasite burden is low.

- Serology:

- Babesia-specific antibody testing should not be used for routine diagnosis of acute babesiosis.

- A B. microti IgG antibody titer of ≥1:1024 or the presence of B. microti IgM antibody are suggestive of active or recent B. microti infection, while a 4-fold rise in Babesia IgG antibody in sera from the time of acute illness to the time of convalescence confirms the diagnosis.

- Distinguishing active from past infection using serology is difficult because most patients who experience acute babesiosis remain seropositive for a year or more after resolution of disease, despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

- Methods include:

- Indirect immunofluorescence assay – routinely used to detect B. microti antibody in blood.

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Western blot

- IDSA 2020 Guideline on Diagnosis and Management of Babesiosis:

- For diagnostic confirmation of acute babesiosis, we recommend peripheral blood smear examination or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) rather than antibody testing (strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence). Comment: The diagnosis of babesiosis should be based on epidemiological risk factors and clinical evidence, and confirmed by blood smear examination or PCR.

- For patients with a positive Babesia antibody test, we recommend confirmation with blood smear or PCR before treatment is considered (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence). Comment: A single positive antibody test is not sufficient to establish a diagnosis of babesiosis because Babesia antibodies can persist in blood for a year or more following apparent clearance of infection, with or without treatment.

Treatment

- Asymptomatic infection:

- A 1-week course of atovaquone plus azithromycin should be considered for any person identified with asymptomatic babesial infection (as determined by blood smear or PCR) for longer than 3 months.

- IDSA 2020 Guideline on Diagnosis and Management of Babesiosis:

- We recommend treating babesiosis with the combination of atovaquone plus azithromycin or the combination of clindamycin plus quinine (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence):

- Atovaquone plus azithromycin is the preferred antimicrobial combination for patients experiencing babesiosis, while clindamycin plus quinine is the alternative choice (associated with more adverse reactions and usually reserved for patients with severe disease).

- The duration of treatment:

- 7 to 10 days in immunocompetent patients

- Extended to at least 6 weeks for highly immunocompromised patients, especially those with impaired antibody production because these patients are more likely to fail a standard course of antimicrobial therapy.

- Clindamycin and quinine is a second choice if atovaquone plus azithromycin cannot be used because

of side effects, limited availability, or cost.

- Patients admitted to the hospital for severe B. microti infection:

- Best treated with IV azithromycin plus oral atovaquone.

- An alternative choice is IV clindamycin plus oral quinine but this regimen should be reserved for patients unresponsive to azithromycin plus atovaquone because quinine commonly causes side effects.

- In selected patients with severe babesiosis, we suggest exchange transfusion using red blood cells (weak recommendation, low-quality evidence):

- Exchange transfusion may be considered for patients with high-grade parasitemia (>10%) or who have any one or more of the following:

- Severe hemolytic anemia and/or

- Severe pulmonary, renal, or hepatic compromise.

- Expert consultation with a transfusion services physician or hematologist in conjunction with an infectious diseases specialist is strongly advised.

- Exchange transfusion may be considered for patients with high-grade parasitemia (>10%) or who have any one or more of the following:

- Monitoring:

- For immunocompetent patients, we recommend monitoring Babesia parasitemia during treatment of acute illness using peripheral blood smears but recommend against testing for parasitemia once symptoms have resolved (strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence).

- For immunocompromised patients, we suggest monitoring Babesia parasitemia using peripheral blood smears even after they become asymptomatic and until blood smears are negative. PCR testing should be considered if blood smears have become negative but symptoms persist (weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence).

- We recommend treating babesiosis with the combination of atovaquone plus azithromycin or the combination of clindamycin plus quinine (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence):

- Clinical practice guidelines from the American Society for Apheresis (ASFA, 2019):

- Red blood cell (RBC) exchange might influence the course of the disease by 3 possible mechanisms of action:

- Lower the level of parasitemia by replacing infected RBCs with non-infected donor RBCs.

- Removal of rigid infected cells to decrease microcirculation obstruction and tissue hypoxia caused by

adherence of RBCs to vascular endothelium. - Removal of cytokines produced by the hemolytic process, including INF-α , TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, nitric oxide, and thromboplastin substances, which can promote renal failure and DIC.

- RBC exchange is indicated for babesiosis patients with heavy parasitemia (typically >10%) or who have significant comorbidities such as significant hemolysis, DIC, pulmonary, renal, or hepatic compromise.

- The greatest advantage of RBC exchange over antibiotic therapy is its rapid therapeutic effectiveness though questions remain as to the effect on morbidity/mortality and exact mechanism of benefit.

- The specific level of parasitemia to perform RBC exchange is unclear but >10% parasitemia in the presence of severe symptoms is the most commonly used guideline to initiate the procedure.

- The specific level to which parasitemia must be reduced to elicit the maximum therapeutic effect is also unclear. Treatment is usually discontinued after achieving <5% residual parasitemia. Decision to repeat the exchange is based on the level of parasitemia post-exchange as well as the clinical condition (ongoing signs and symptoms). Treating physicians should be aware, however, of the potential for rebound in parasitic burden post-RBC exchange and thus, post-exchange parasitemia surveillance is crucial.

- Red blood cell (RBC) exchange might influence the course of the disease by 3 possible mechanisms of action:

Prognosis

- All-cause mortality:

- <1% of clinical cases

- about 10% in transfusion transmitted cases

- Up to 20% in immunocompromised patients with severe babesiosis

- Relapsing disease and treatment failures are primarily observed among patients with asplenia and/or other immune deficits.

Cohorts

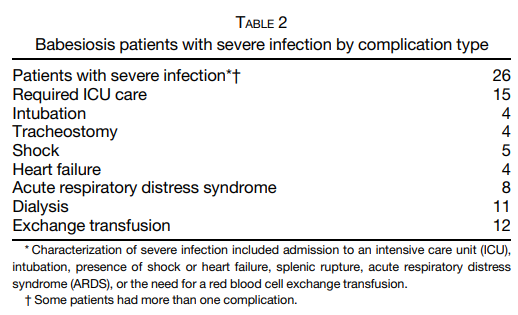

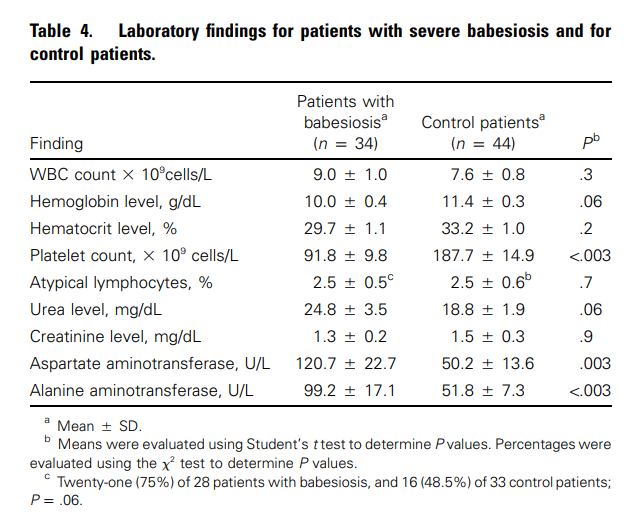

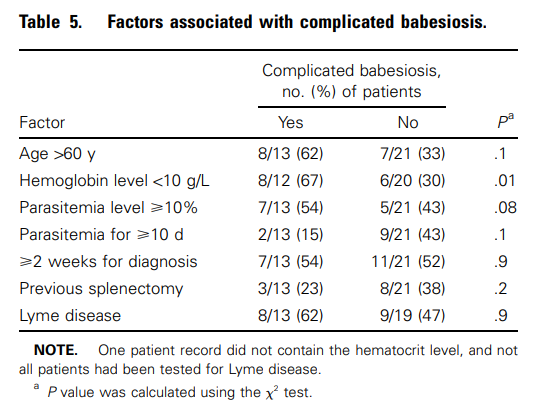

Cohort of 34 patients with severe babesiosis:

- A case-control study:

- 34 patients with severe babesiosis.

- Control patients were selected from a sample of the records from hospitals for patients admitted and discharged with a diagnosis, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) of fever of unknown origin; matched for age and sex.

- Average time from onset of symptoms to final diagnosis of babesiosis was 15.4 days.

- 32% of the patients recalled receiving a tick bite.

- Of the patient characteristics and symptoms, the presence of malaise, arthralgias and myalgias, and shortness of breath were all significantly associated with Babesia infection, whereas other symptoms were not.

- 94.1% of the patients had an associated comorbidity, including:

- Splenectomy

- Coronary artery disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Congestive heart failure

- Lyme borreliosis coinfection occurred in 53.1% of the patients.

- Laboratory findings included:

- Mean WBC count was 9.0 cells x 10^9/L.

- Mean hemoglobin level was 10.0 g/dL, lower compared with control patients.

- Mean platelet count was 91.8 x 10^9/L, lower compared with control patients.

- No increase in mean number of atypical lymphocytes.

- Liver enzymes were significantly higher in the affected patients when compared with the control patients, with a mean serum aspartate transaminase (AST) of 120.7 U/L and a mean serum alanine transaminase (ALT) of 99.2 U/L.

- Complications of severe Babesia infection included:

- Acute respiratory failure in 7 (20.6%) patients

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation in 6 (17.6%) patients

- CHF in 4 (11.8%) patients

- Renal failure in 2 (5.9%) patients

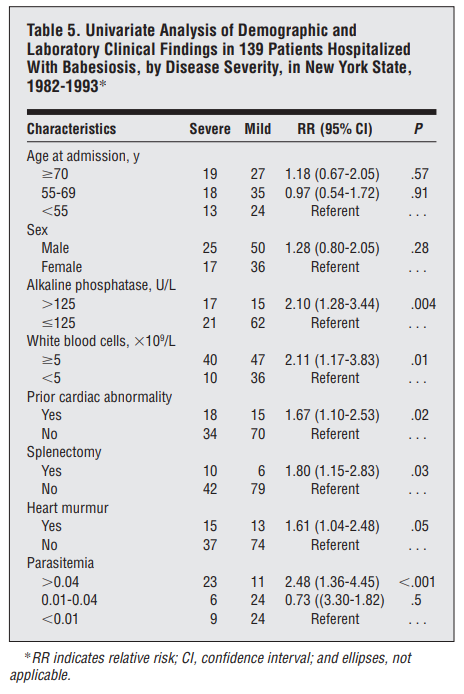

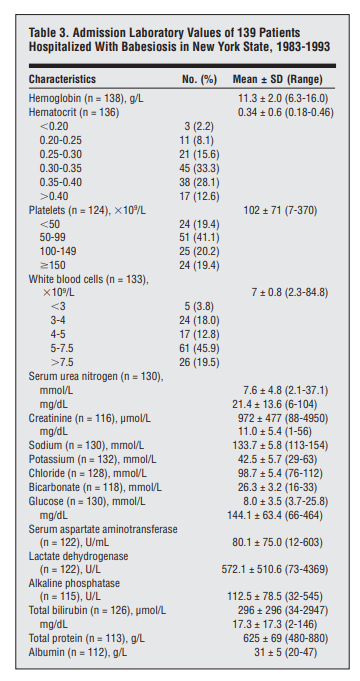

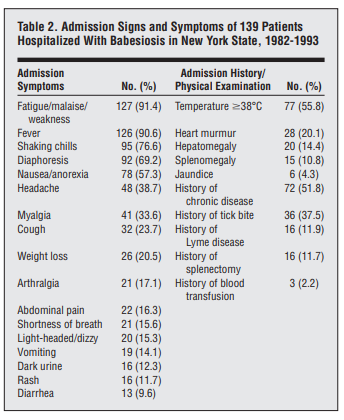

Cohort of 139 hospitalized cases:

- Human babesiosis cases were collated from state communicable disease reports and medical records of patients hospitalized from 1982 to 1993.

- The majority of patients were admitted during June through August, with very few admissions during winter.

- The most common symptoms included:

- Fatigue/malaise/weakness (91.2%)

- Fever (90.6%)

- Shaking chills (76.6%)

- Diaphoresis (69.2%)

- Nausea/anorexia (57.3%)

- Physical findings included:

- Temperature higher than 38°C (55.8%)

- Heart murmur (20.1%)

- Hepatomegaly (14.4%)

- Splenomegaly (10.8%)

- Only 6 patients (4.3%) had jaundice

- 51.8% had a history of chronic disease, 11.9% had a history of Lyme disease, and 11.7% had undergone splenectomies.

- More than one third (37.5%) of the patients reported having a tick bite within 30 days prior to their hospitalization.

- The most common laboratory abnormalities on admission included:

- Mean hematocrit was 34% and the mean hemoglobin was 113 g/L.

- Fifty-nine percent of the patients had hematocrit levels lower than 35%.

- 35% had total white blood cell counts lower than 5 x 10^9/L

- 60.5% had platelet counts lower than 100 x 10^9/L.

- Liver function studies on admission showed elevations of mean levels of LDH (572 U/L), AST (80 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (113 U/L), and total bilirubin (296 µmol/L [17.3 mg/dL]).

- During hospitalization, the mean hematocrit of the patients decreased to 27%, with 90.3% decreasing to less than 35%.

- The mean change from hematocrit on admission to the lowest value during hospitalization was 6.1 percentage points.

- Total mean bilirubin values increased from 296 to 361µmol/L (17.3-21.1 mg/dL).

- Thirty-five patients (25.2%) were admitted to intensive care units during hospitalization, and 8 (5.8% of total cases) required intubation.

- The majority of treated patients received clindamycin hydrochloride (n = 110, 79.1%) and quinine sulfate (n = 106, 76.3%).

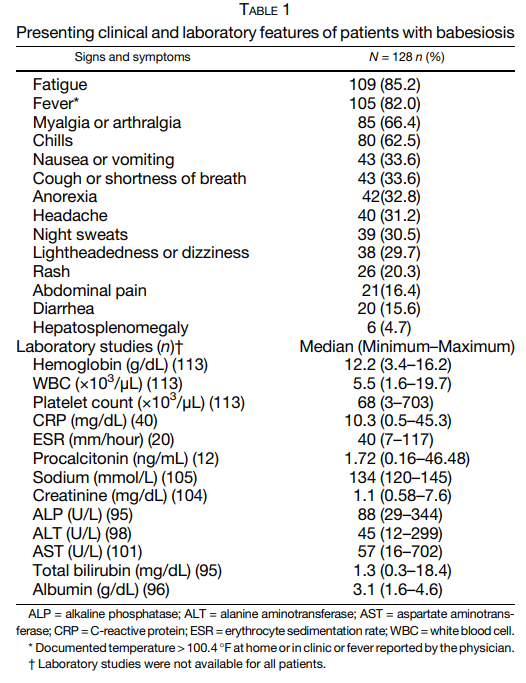

Cohort of 128 patients with babesiosis:

- Attachment of a tick was reported by 41.4% of patients

- Chronic medical conditions were present in 99 (77.3%) patients including

- 14 (10.9%) with asplenia

- 12 (9.4%) that were immunocompromised

- Of patients with B. microti, evidence of additional infections was found in 47 (36.7%) of patients including 38 (29.7%) patients with confirmed or probable Lyme disease, six (4.5%) with anaplasmosis, and three (2.3%) with both evidence of Lyme disease and anaplasmosis.

- Clinical and laboratory findings:

- fatigue and fever were observed in greater than 80% of patients.

- Myalgia or arthralgia and chills were each present in greater than 60% of patients.

- Less common symptoms reported were:

- Cough or shortness of breath (33.6%)

- Anorexia (32.8%)

- Headaches (31.2%)

- Night sweats (30.5%).

- Gastrointestinal symptoms including:

- Anorexia (32.8%)

- Nausea and/or vomiting (33.6%)

- Diarrhea (15.6%)

- Hemoglobin (Hb) values of < 12 gm/dL were recorded in 44.2% of patients at diagnosis.

- Median platelet count at diagnosis was 68 (3–703) × 103 /μL with 69.9% of patients having a platelet count less than 100,000 × 103 /μL.

- Inflammatory markers were elevated in most patients, including 92.5% of patients with C-reactive protein (CRP; median 10.24 [0.5–45.3] mg/dL) obtained, 100% of patients with procalcitonin (median 1.72 [0.16–46.48] ng/mL) obtained and 70% of patients with erythrocyte sedimentation rate ( median 40 [7–117] mm/hour) obtained.

- Median total bilirubin at presentation was 1.3 (0.3–18.4) mg/dL

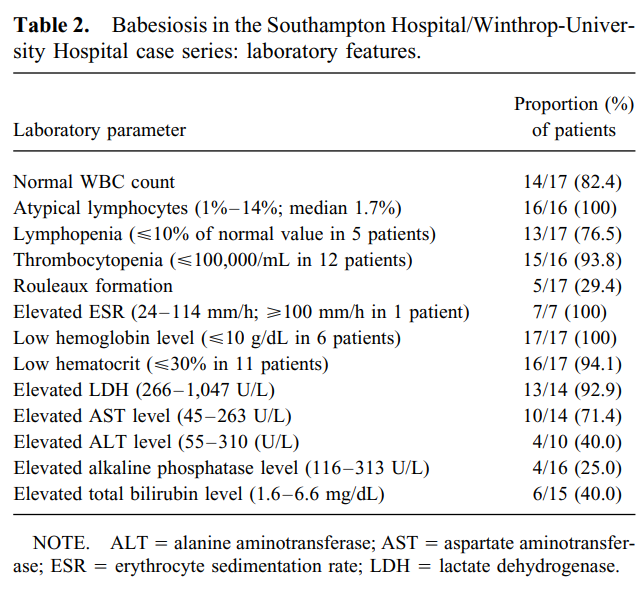

Cohort of 17 patients with babesiosis:

- 76.5% had lymphopenia.

Prev

1 / 0 Next