Hematology and the transgender patient

Prev

1 / 0 Next

Prev

1 / 0 Next

Hematology and the transgender patient

Our patient self-reported as transgender. This is a good opportunity to briefly discuss hematology and transgender medicine. Up to 0.6% of the United States population identified as transgender in 2016. Transgender women are those assigned male sex at birth who identify as female. Transgender men are those who were assigned female sex at birth but identify as male, as is the case with the current patient. Transgender people may pursue any of a number of gender-affirming interventions that include:

- Cross-sex hormone therapies (CSH)

- Surgery

Overview:

- Transgender men:

- Testosterone:

- Taken to:

- Induce virilization, including:

- Deepening of the voice.

- An increase in facial and body hair.

- A more masculine body composition.

- Psychological and sexual changes.

- Suppress feminizing characteristics.

- Induce virilization, including:

- Testosterone formulations:

- Typically include weekly or biweekly intramuscular or subcutaneous injections (equally effective).

- Transdermal testosterone preparations can also be used.

- Sufficiently suppresses estrogen and increase testosterone levels within the normal physiological male range.

- Taken to:

- Gender-affirming surgeries include:

- Mastectomy

- Facial masculinization

- Genital reconstruction through:

- Metoidioplasty (i.e., creation of a phallus from a hormonally-enlarged clitoris).

- Phalloplasty (i.e., multistep construction of a neophallus, often with a free flap of tissue taken from the forearm).

- Testosterone:

- Transgender women:

- Often take exogenous estrogen, which feminizes a patient’s characteristics.

- Formulations typically include oral estrogens or transdermal patches.

- Often also use antiandrogens to inhibit production of testosterone and other male sex hormones, helping to suppress masculinizing features.

- Gender-affirming surgeries include:

- Breast augmentation

- Orchiectomy

- Vaginoplasty

- Laryngeal surgery

- Facial feminization

Hematological concerns:

- Transgender men:

- Increased risk of developing cancer – should be screened for breast and cervical cancer, alongside the general cisgender female population.

- Increased risk of polycythemia or erythrocytosis:

- Testosterone has a dose-dependent stimulating effect on erythropoiesis.

- Testosterone treatment over a mean period of two years maintains the hematocrit and hemoglobin within the adult male reference range.

- Testosterone treatment may result in secondary erythrocytosis, a potentially serious adverse effect as it may be associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events by virtue of an increase in blood viscosity.

- Prevalence of erythrocytosis (hematocrit > 0.50) is reported to be:

- 5% – 66% in testosterone-treated hypogonadal cis men.

- Highest risk of erythrocytosis with injectable testosterone therapy.

- Biggest increase in Hct occurs in the first 3 months to 1 year.

- 11.5% in testosterone-treated trans men.

- 5% – 66% in testosterone-treated hypogonadal cis men.

- Erythrocytosis may be associated with increased thromboembolic risks in this population, though the evidence for this is decidedly weak.

- The Endocrine Society recommends regular monitoring of testosterone levels, hematocrit, liver function, blood pressure and lipid.

- The ideal management of erythrocytosis remains unknown, with testosterone dose reduction having the potential to limit the desired gender-affirming effects.

- Two cohort studies of trans men using testosterone:

- In one study of 1073 trans men using testosterone:

- Erythrocytosis occurred in 11% (hematocrit > 0.50 L/L), 3.7% (hematocrit > 0.52 L/L), and 0.5% (hematocrit > 0.54 L/L).

- In another study of 923 transgender/non-binary individuals receiving testosterone:

- Testosterone cypionate was the predominant formulation administered in 837/923 patients (90%).

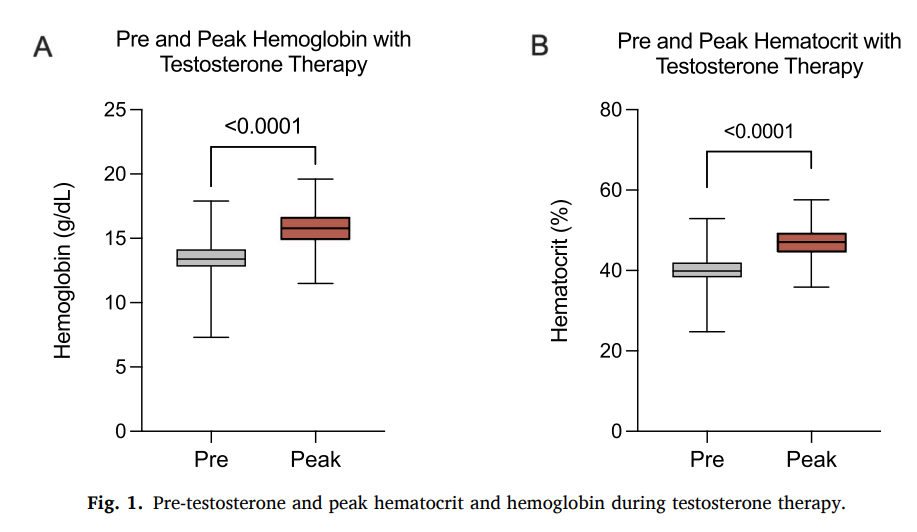

- The mean baseline and peak hemoglobin were 13.5 and 15.7 g/d, respectively (mean difference 2.54 g/dL, p < 0.0001).

- Mean baseline and peak hematocrit were 40.2% and 47.0%, respectively (mean difference 6.84%, p < 0.0001).

- The mean time-to-peak for hemoglobin and hematocrit was 31.2 months.

- During this time, 41/519 patients (7.8%) developed a hemoglobin greater than 17.5 g/dL compared to 104/519 patients (20%) who developed a hematocrit over 50%.

- The majority of those who developed erythrocytosis were receiving injectable formulations of testosterone, while only 21 patients who developed erythrocytosis were receiving transdermal formulations.

- In those who developed erythrocytosis, testosterone dose reduction was the most common intervention performed in 42%, 4.8% underwent therapeutic phlebotomy, and no change or observation compromised the rest.

- Thromboembolic events occurred in 5/519 patients (0.9%) with four (80%) of these patients meeting criteria for erythrocytosis at any time during their care. The authors concluded “despite the high incidence of erythrocytosis, thromboembolic events and hospitalizations involving erythrocytosis were uncommon”.

- In one study of 1073 trans men using testosterone:

- Transgender women:

- Increased risk of venous thromboembolism while taking exogenous estrogen.

Prev

1 / 0 Next