From MCV to clinical encounter

The patient has a mean cell volume (MCV) of 63 fL. Which one of the following questions would provide the most useful information?

So, we are left with iron deficiency and/or thalassemia as the most likely etiologies (there are other much less common causes of microcytosis including fragmentation syndrome [excess schistocytes], sideroblastic anemia, lead poisoning and hyperthyroidism):

You ask the patient how long she has known about the condition. She says that someone told her many years ago that she has thalassemia, but she cannot remember the details. If you could have one test to order to sort this out what would you choose?

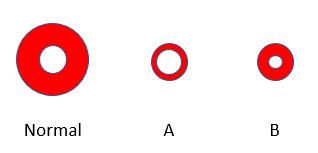

If this patient has thalassemia minor, what would you expect to find?

If this patient has iron deficiency anemia, what would you expect to find?

The patient’s red cell count is, in fact, high at 5.65 x 1012/L (normal range is 3.9-5.2 x 1012). Does this mean the patient has polycythemia?

Polycythemia is defined by a patient’s hemoglobin or hematocrit, which are surrogate markers for red cell mass.

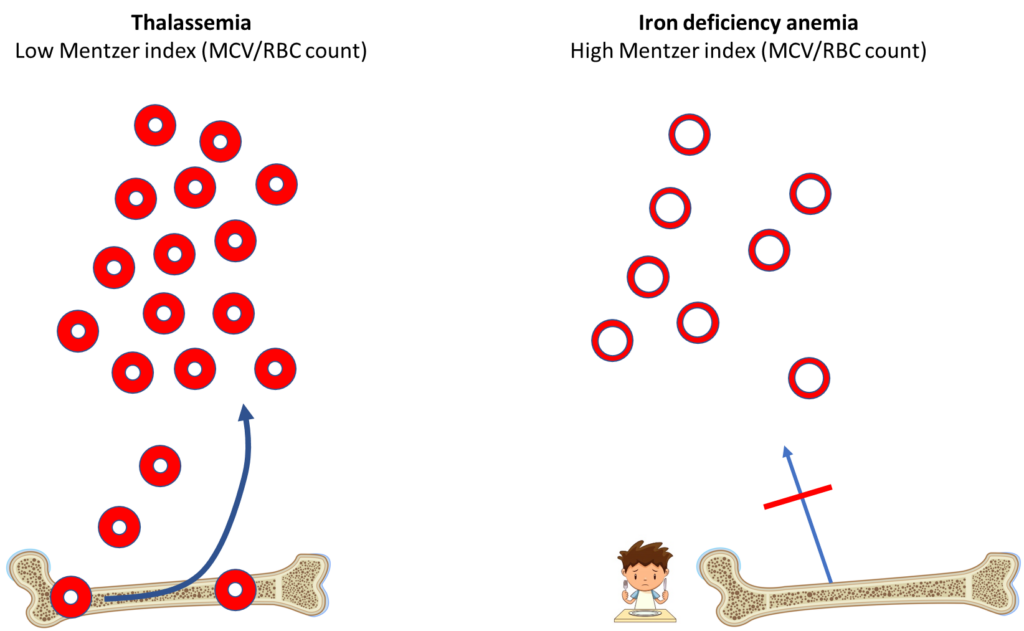

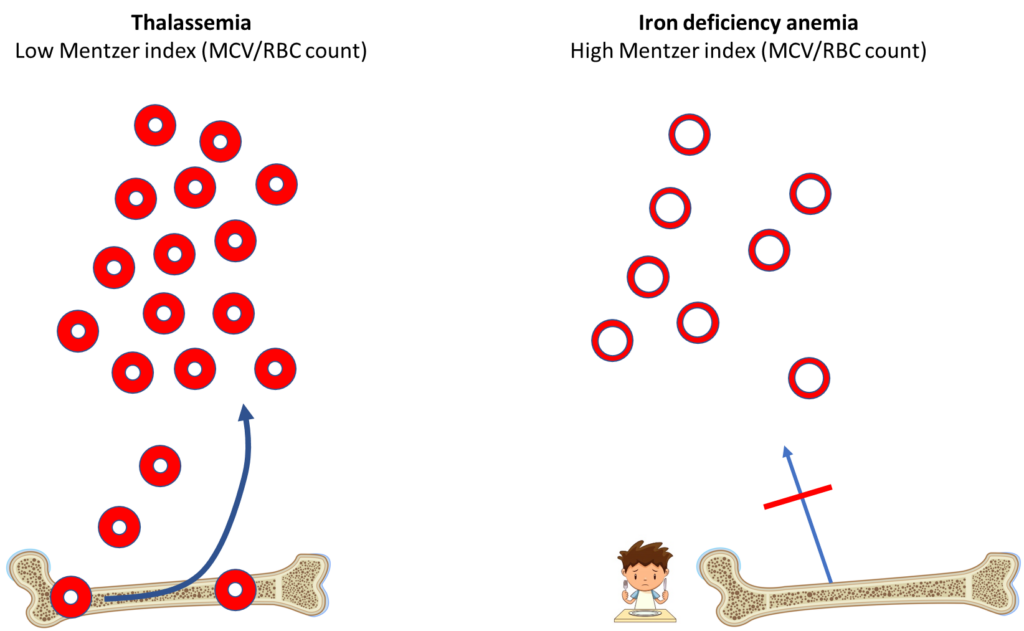

The Mentzer index is one of many formulas that has been proposed to help distinguish between iron deficiency anemia and beta thalassemia based on parameters from the complete blood count.

A Mentzer index of < 13 is suggestive of thalassemia, > 13 is suggestive of iron deficiency. Thus, this patient’s Mentzer index of 11 indicates a likely diagnosis of thalassemia minor.

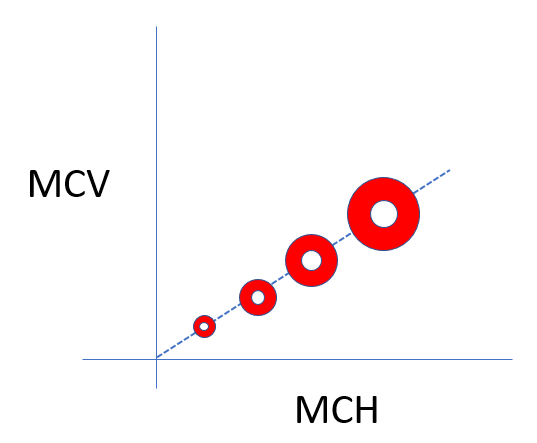

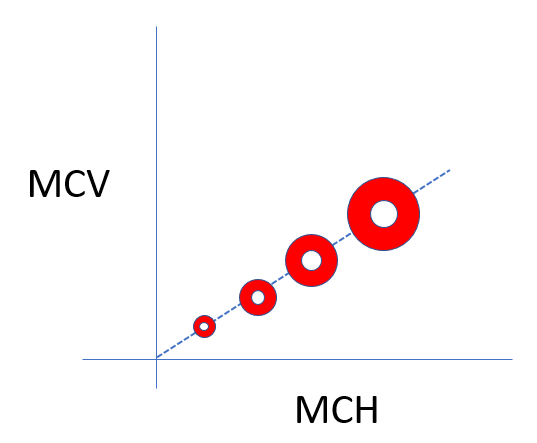

What is the Mentzer index really trying to say? That the patient with thalassemia minor is producing more red cells to compensate for the small red cell volume to reach a normal hematocrit.

The patient’s hemoglobin is 12.7 g/dL and hematocrit 35.6%.

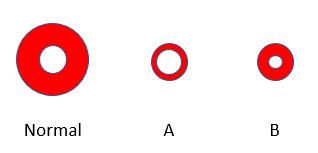

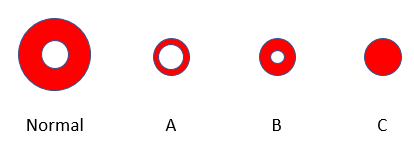

Based on this information, which red cell schematic is likely to resemble the patient’s?

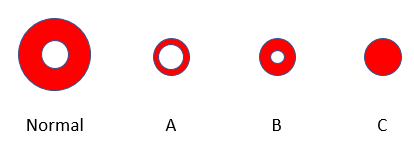

This value for the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) is at the high end of normal (normal range 32-36 g/dL). In fact, previous labs for the patient show her MCHC ranging between 35.5 g/dL and 37.3 g/dL. In other words, the patient’s red cells are approaching the phenotype shown in panel C:

Does that provide any clues about the underlying diagnosis?

Hold on to that thought. We will return to this question in a few slides. Let’s first look at the CBC in all its glory (next slide).

Here is the patient’s complete blood count when you see her:

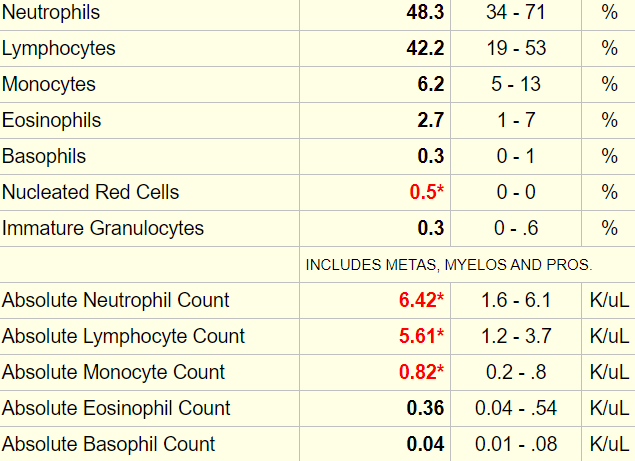

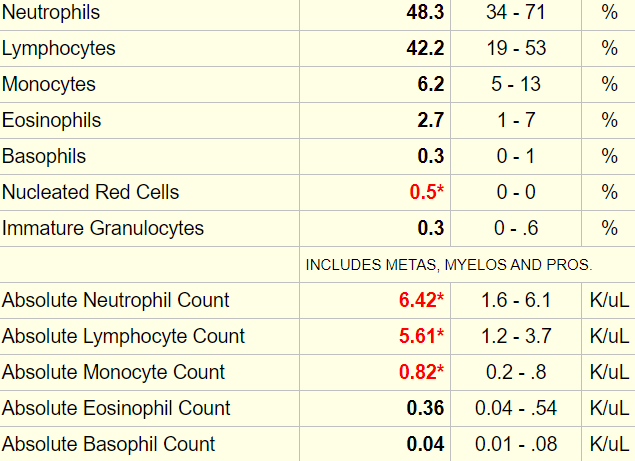

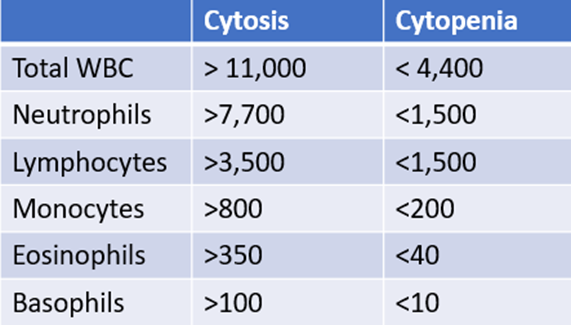

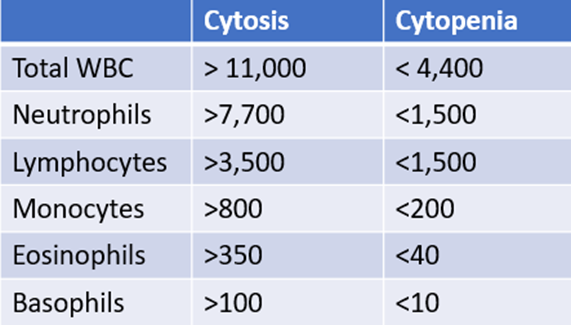

Any time there is an abnormal white cell count, it is important to order a differential. Here are the results (accompanied by a cheat sheet for diagnosing lower- and higher-than-normal values):

Ideally, we would like a reticulocyte count, but one was nor ordered in this case. Based on what you know so far about the patient, what would you expect the reticulocyte count to be:

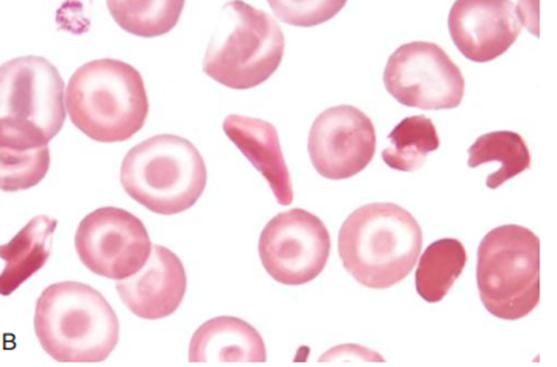

The patient’s peripheral smear resembles the one shown below:

So far, everything is pointing towards thalassemia minor with two exceptions:

- She has a high normal and at times elevated mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC).

- She has many targets and some irregularly contracted red cells on the peripheral smear.

What are these data suggestive of:

What would you expect from her history?

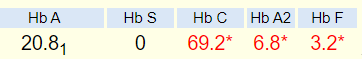

This is a 38 year-old woman referred to you for evaluation of microcytic anemia. She has a long history of microcytosis. She recently transferred care to a new PCP, who ordered a hemoglobin electrophoresis. The results showed HbA 20.8%, HbC 69.2%, HbA2 6.8% and HbF 3.2%. She denies a history of anemia, iron deficiency, or blood transfusions. She denies symptoms of pica, headache, restless legs, alopecia, brittle nails, shortness of breath on exertion or chest pain. She has insulin-dependent diabetes. She has had breast reduction surgery and two Caesarian sections. There is no known family history of thalassemia or other hemoglobinopathy. She is from Trinidad, she is a non-smoker and she drinks socially. She works as a nurse’s aid. In addition to insulin, she takes metformin. She is allergic to sulfonamides.

The following describes this patient’s physical exam when you see her in the clinic:

General appearance: Looks well, in no distress

Vital signs: Heart rate 2/min, blood pressure 133/70 mmHg, respiratory rate 13/min, T 99.2oF

Head and neck: No scleral icterus, no lymphadenopathy

Chest: Normal to inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation

CVS: Heart sounds normal, no S3 or S4, no murmur

Abdomen: Non-tender, no hepatosplenomegaly

CNS: No focal changes

Extremities: Normal

Integument: No rash

Let’s take a closer look at her hemoglobin electrophoresis:

How would you interpret this?

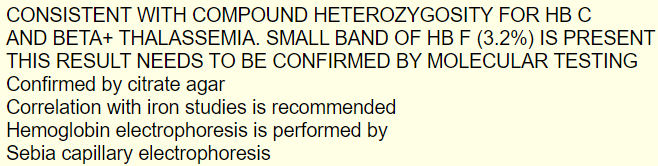

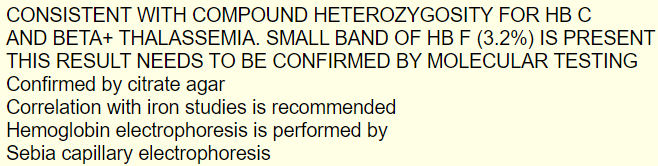

The following was the report of the patient’s hemoglobin electrophoresis:

Let’s see how Hb electrophoresis can used to discriminate between different hemoglobinopathies. Typically, samples are run on cellulose acetate at alkaline pH, and then on an agarose gel at acid pH. Different types of hemoglobin migrate in distinct patterns on each gel allowing for identification of the relevant hemoglobin:

We began this exercise by discussing the differential diagnosis of microcytosis. The leading causes are iron deficiency anemia, thalassemia and inflammation. There are rarer causes such as hyperthyroidism, certain congenital anemias and conditions associated with increased schistocytes. Where does Hb C fit into all this? In the next two slides, we will consider hemoglobinopathies in general and will then place Hb C into context.

Hemoglobinopathies

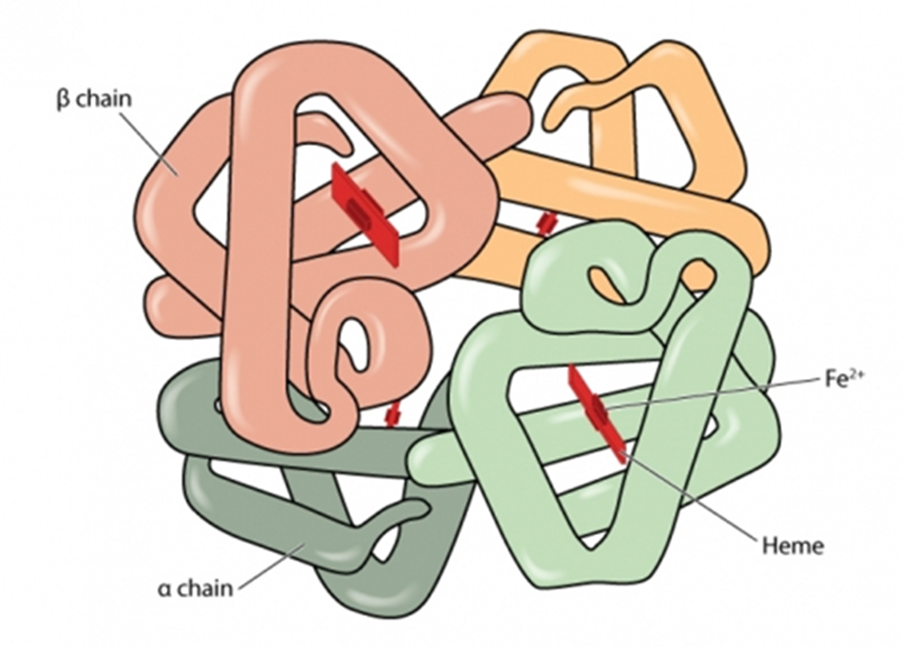

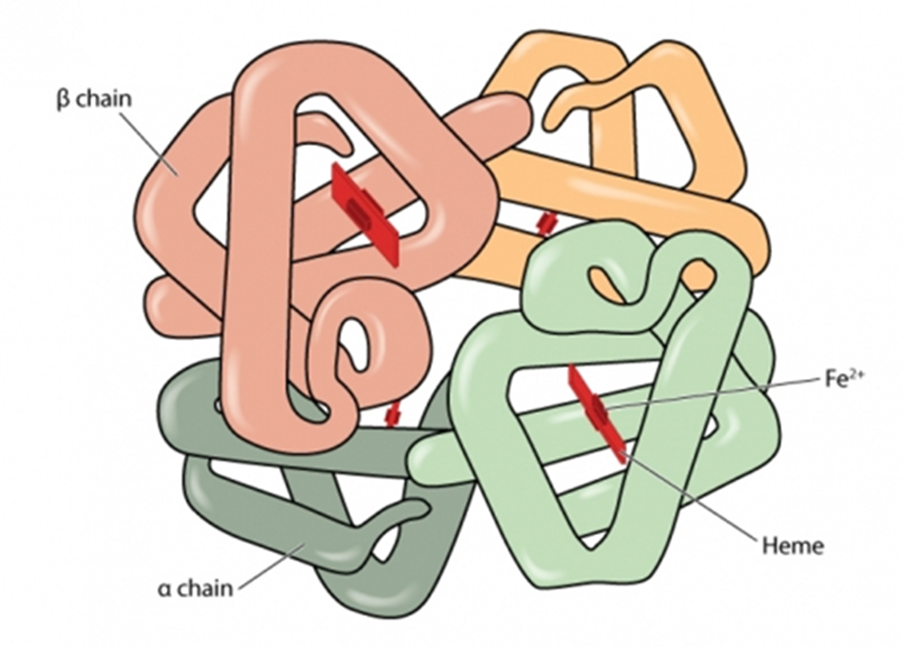

Hemoglobinopathies are a group of recessively inherited genetic conditions affecting the alpha or beta globin chains of hemoglobin. Hemoglobinopathies are the most common autosomal recessive disorder worldwide, with 7% of the global population carrying an abnormal hemoglobin (Hb) alpha or beta globin chain allele.

Hemoglobinopathies may be split into 2 groups, one leading to quantitative changes in hemoglobin, the other to qualitative changes:

- Thalassemia syndromes:

- Quantitative defect caused by decreased expression of one of the two globin chains of the hemoglobin molecule, α (HBA) and β (HBB).

- Decreased expression can result from:

- Deletion of the structural gene(s).

- Mutations that result in decreased RNA synthesis, processing, or stability.

- Mutations resulting in decreased protein synthesis or stability.

- The decrease in expression of one of the globin chains results in accumulation of excess polypeptides encoded by the unaffected gene. This chain imbalance causes abnormal RBC maturation, resulting in microcytosis as the characteristic laboratory abnormality.

- Thalassemia syndromes include:

- Alpha thalassemia

- Beta thalassemia

- Hb E (here’s the catch – Hb E actually has a thalassemia phenotype)

- Structural hemoglobin variants:

- The hemoglobin variants are caused by amino acid substitutions in either globin chain.

- Clinical disease includes:

- Thalassemia-like phenotype

- Sickling

- Hemolysis due to unstable hemoglobins

- Hemoglobins associated with altered oxygen affinity

- Hemoglobins in which iron cannot be maintained in the ferrous (Fe2+) state

- The main Hb abnormalities worldwide are:

- Hb S

- Hb C

- Hb E

- Rarer abnormalities that may have clinical significance include:

- Hb D

- Hb OArab

- Hb Lepore

As can be appreciated from the previous slide, there are many different kinds of hemoglobinopathy. In fact, more than 1,800 hemoglobin variants have been characterized! The good news is that only a small subset are associated with microcytosis. These include:

- Those with a thalassemia phenotype

- Beta thalassemia

- Alpha thalassemia

- Hb E

- Hb C

All of this is to say, if you are working up a patient with microcytosis who you think has thalassemia, you should consider Hb C and Hb E in the differential diagnosis, but you don’t have to concern yourself with any of the other hundreds of hemoglobin variants.