Labs

Let’s begin with the patient’s complete blood count (CBC):

| WBC | Hb | Hct | MCV | MCHC | RDW-SD | PLT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.0 | 8.1 | 23.4 | 82 | 34.6 | 48.1 | 11 |

What’s what: WBC, white blood cell count; Hb, hemoglobin; MCV, mean cell volume; MCHC, mean cellular hemoglobin concentration; RDW-SD, red cell distribution width-standard deviation; platelets, PLT; Normal values: WBC 5-10 x 109/L, RBC 4-6 x 1012/L, Hb 12-16 g/dL, Hct 35-47%, MCV 80-100 fL, MCHC 32-36 g/dL, RDW-SD < 45%, platelets (PLT) 150-450 x 109/L

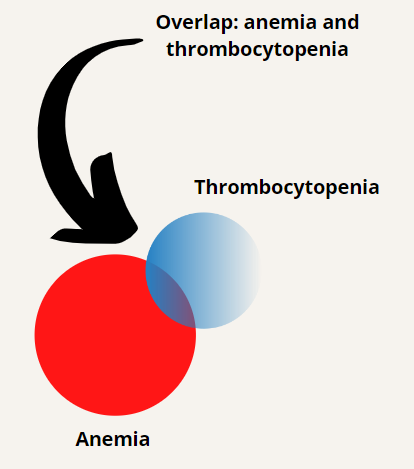

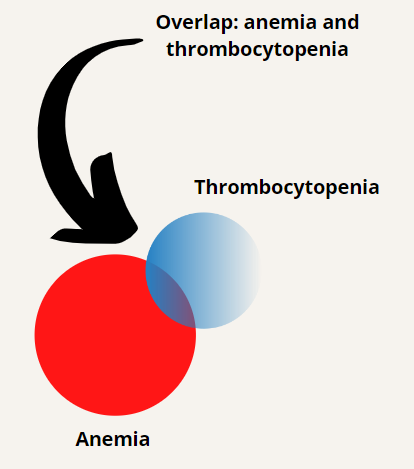

The patient has leukocytosis, anemia and thrombocytopenia.

A white cell differential was unremarkable, revealing an isolated neutrophilia (not shown) without evidence of a left shift. This finding is non-specific, possibly secondary to stress or bleeding.

In terms of making a diagnosis, our best bet is to focus on the anemia and thrombocytopenia. Let’s begin with a differential diagnosis for anemia (though we could just as easily begin with causes of thrombocytopenia) and then see how the concomitant thrombocytopenia helps to narrow the differential.

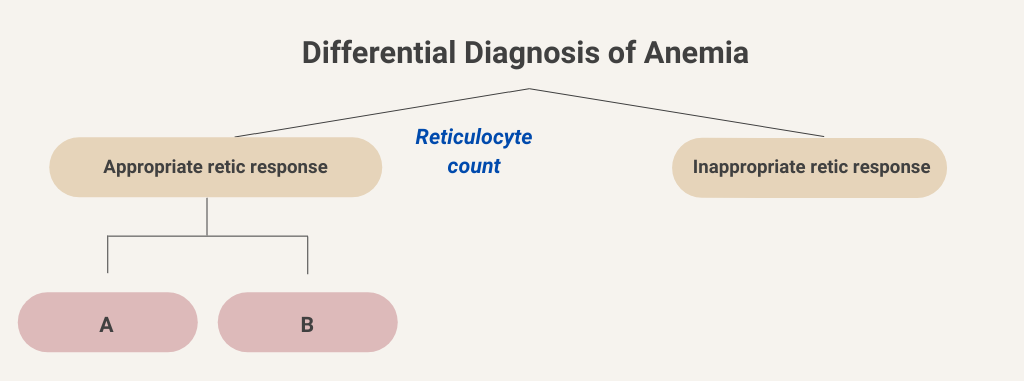

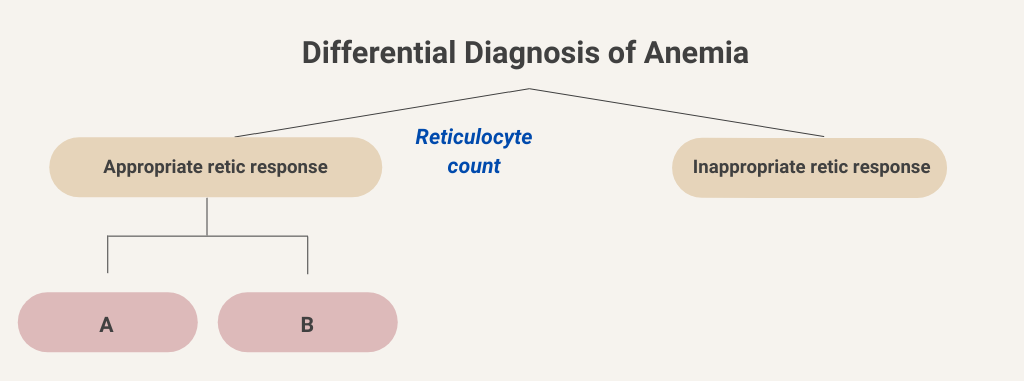

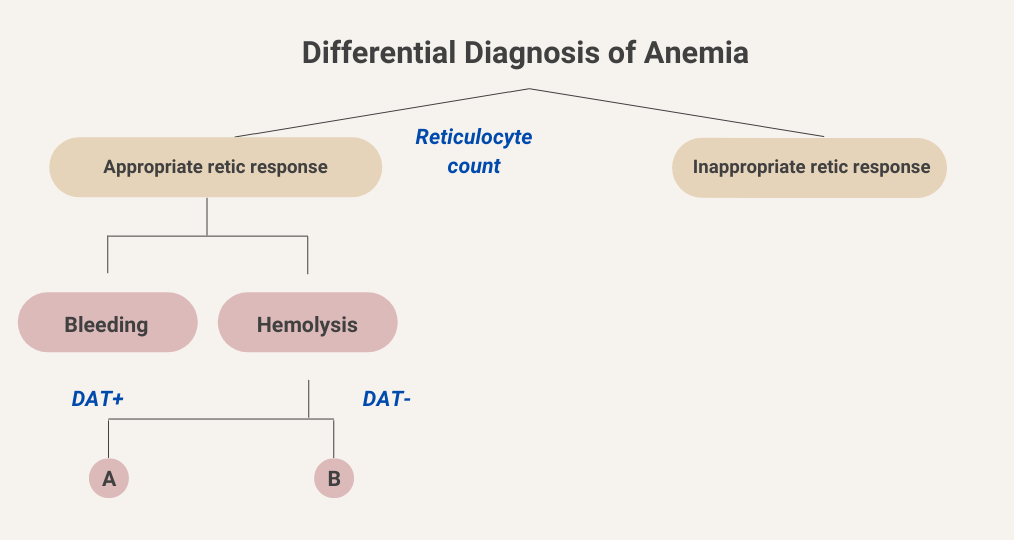

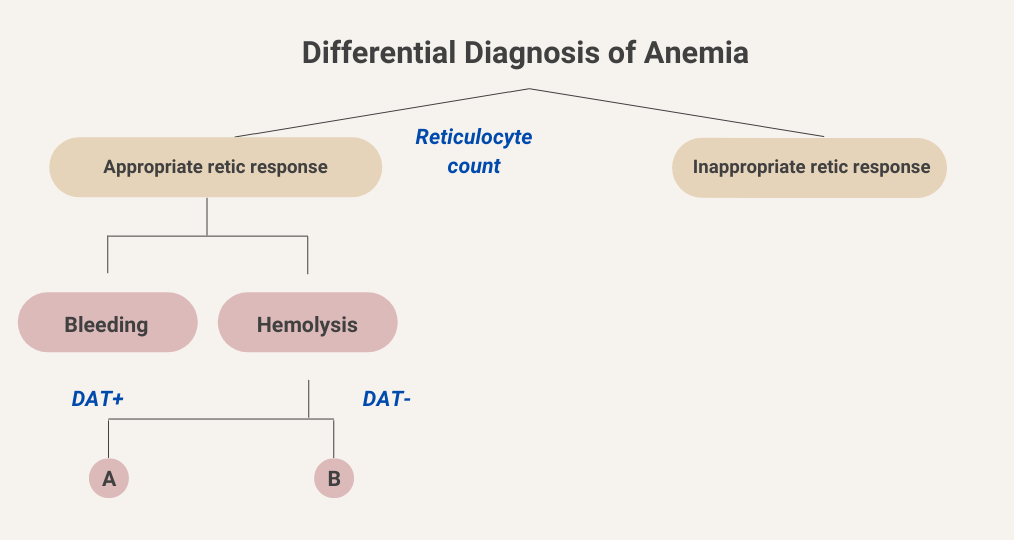

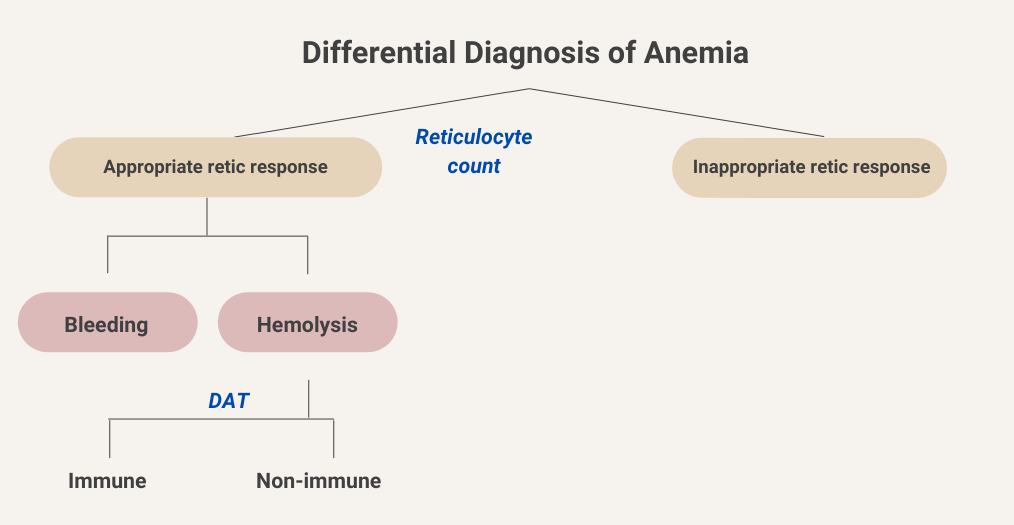

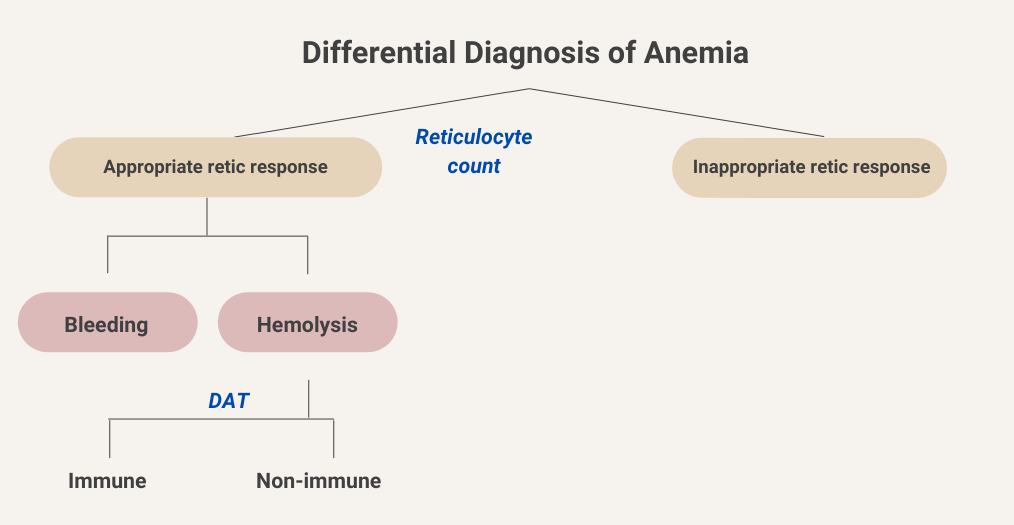

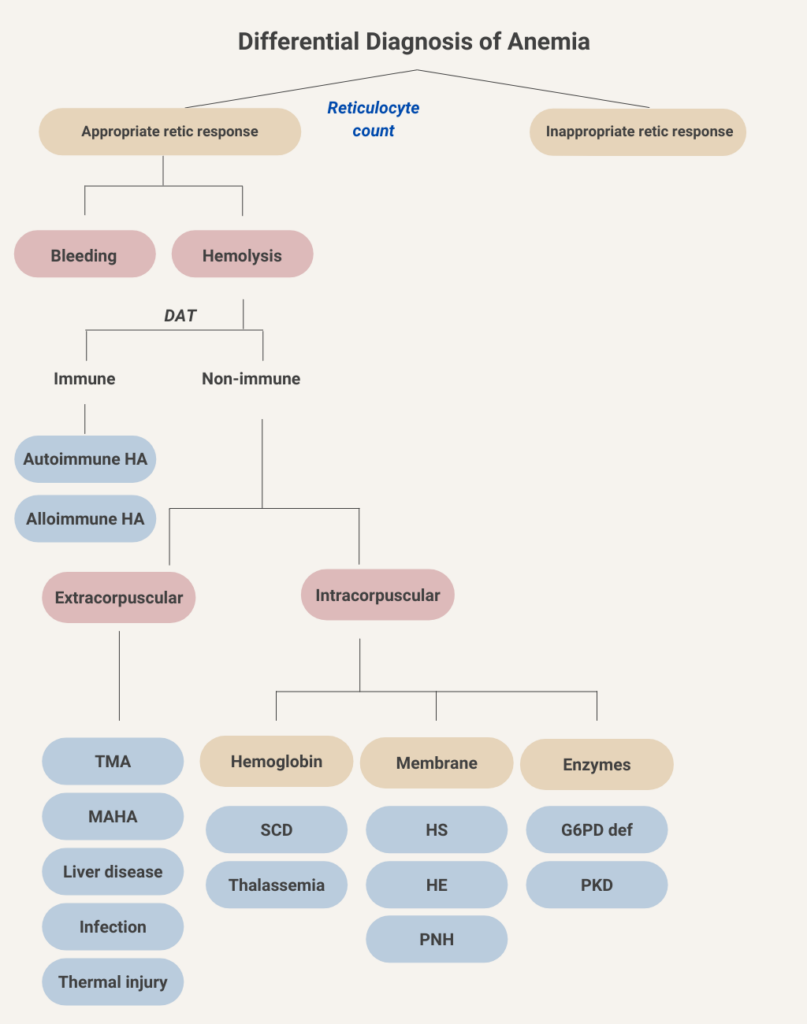

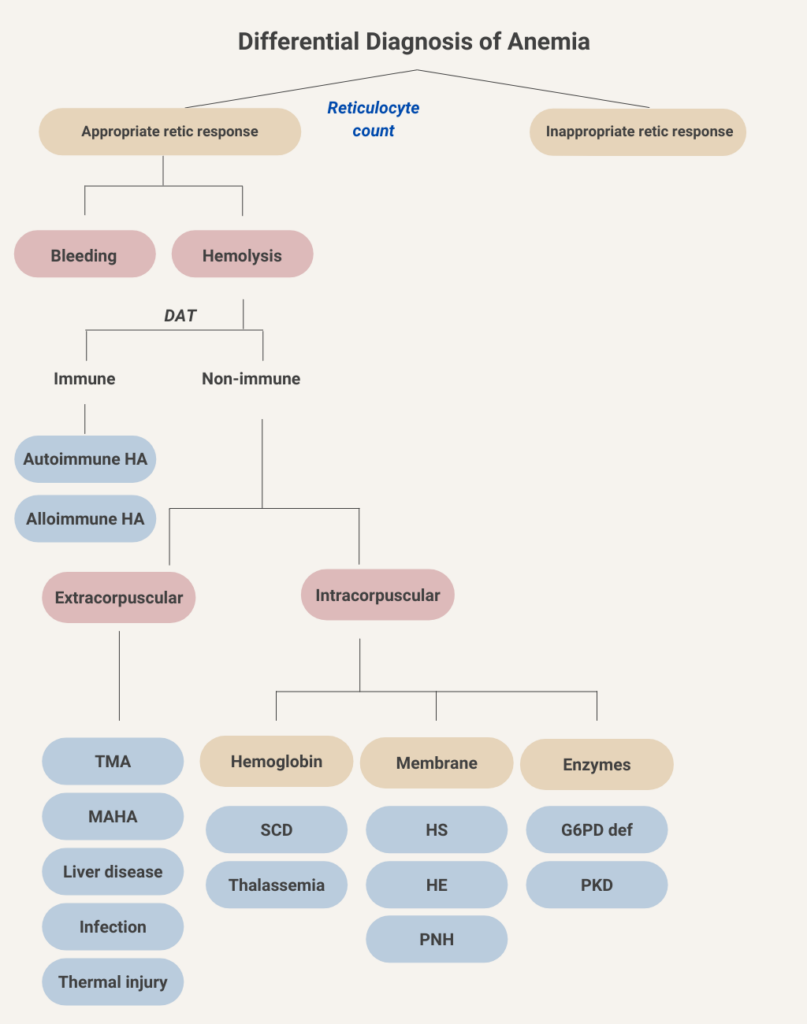

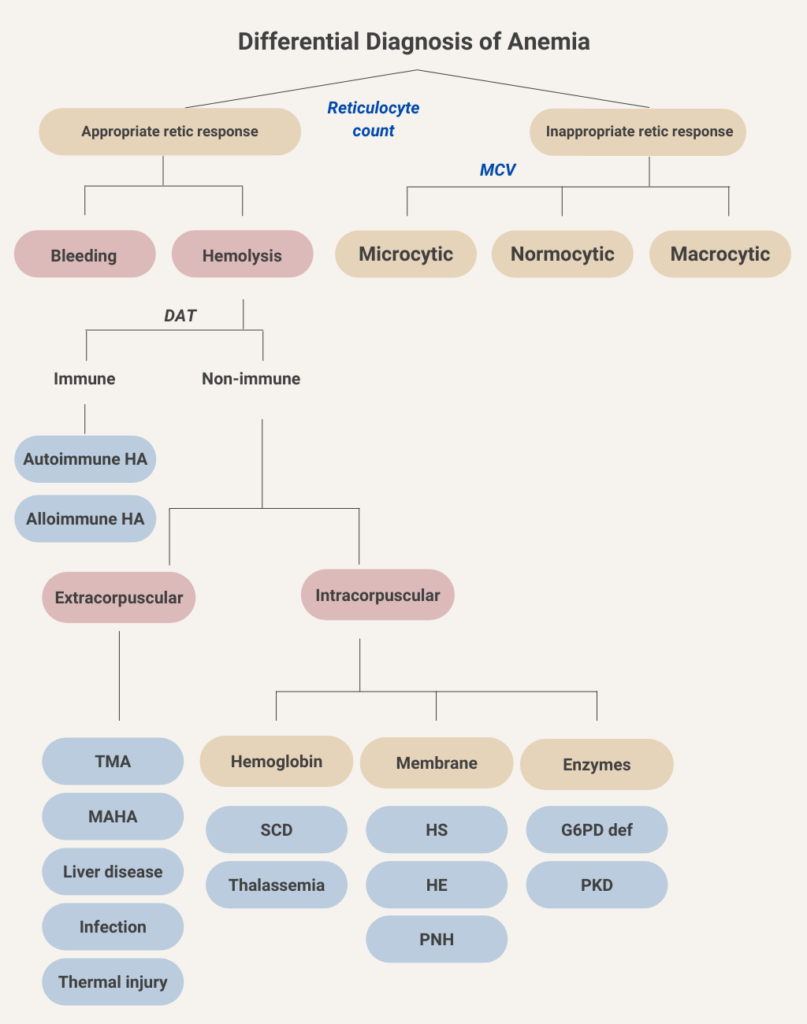

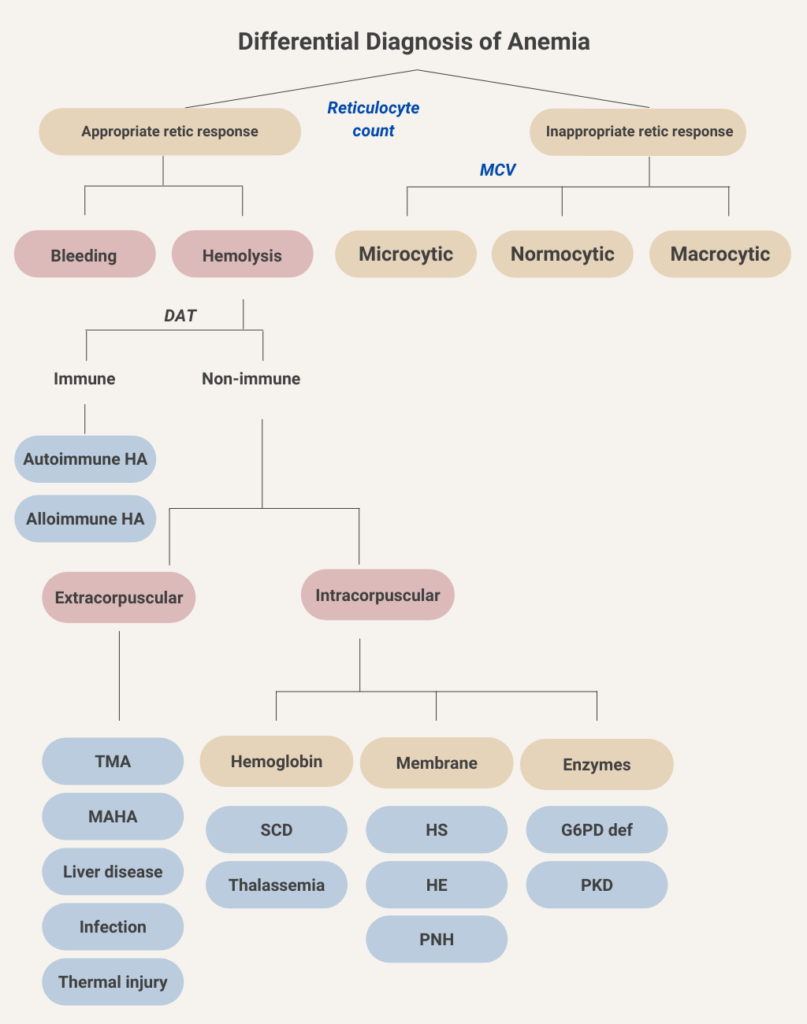

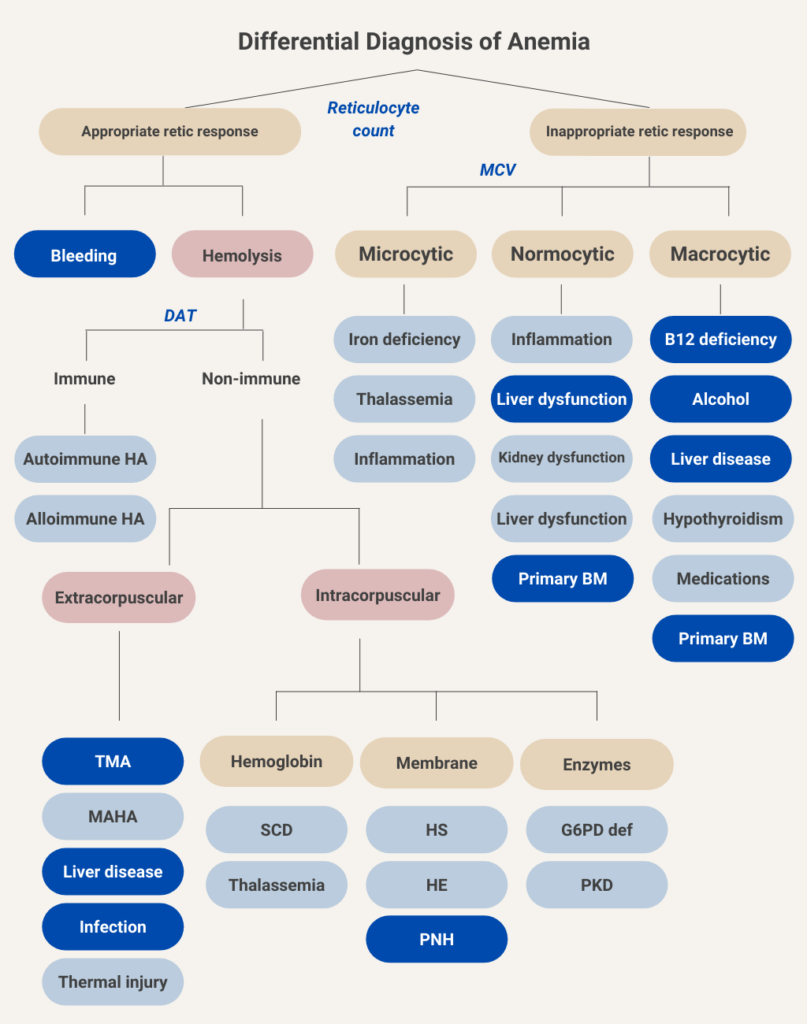

We will begin at the top of the algorithmic tree by dividing anemia into those causes associated with an appropriate reticulocyte count (we will come back to what that means in a bit) and those associated with an inappropriately low reticulocyte response. Let’s consider the side of the ledger with an appropriate reticulocyte response.

Active bleeding as a cause of anemia is usually clinically apparent from the history and/or a change in the vital signs. Hemolytic anemia can be further divided into causes that are positive for direct antiglobulin test (DAT, otherwise known as the Coombs test) and those that are DAT negative. Let’s consider DAT-positive (DAT+) vs. DAT-negative (DAT-) “buckets”.

Let’s stick with the hemolysis branch for now.

In the following sorting exercise, drag the card on the top with a hemolytic disease/condition into the appropriate diagnostic bucket on the bottom.

You’re doing great! In this schematic, we have filled in the various causes of immune and non-immune hemolytic anemia. Immune-mediated (DAT-positive) hemolytic anemia may be divided into allo- and autoimmune causes. Non-immune causes are further separated into extracorpuscular and intracorpuscular etiologies. In extracorpuscular non-immune hemolytic anemia, the red bloods cell are intrinsically normal, but suffer collateral damage from their interactions with the environment, for example by passing over fibrin strands in microvessels (as occurs in thrombotic microangiopathy), by undergoing turbulent flow through paravalvular leaks (causing valve hemolysis), or by being exposed to toxins related to chronic liver disease or to certain pathogens. Intracorpuscular causes include those conditions in which the primary defect is in the red cell, in either its hemoglobin molecule, its membrane structure or its intracellular enzymes. Intracorpuscular non-immune hemolytic anemia is almost always hereditary in nature. One exception is paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), which is an acquired red cell membrane disorder.

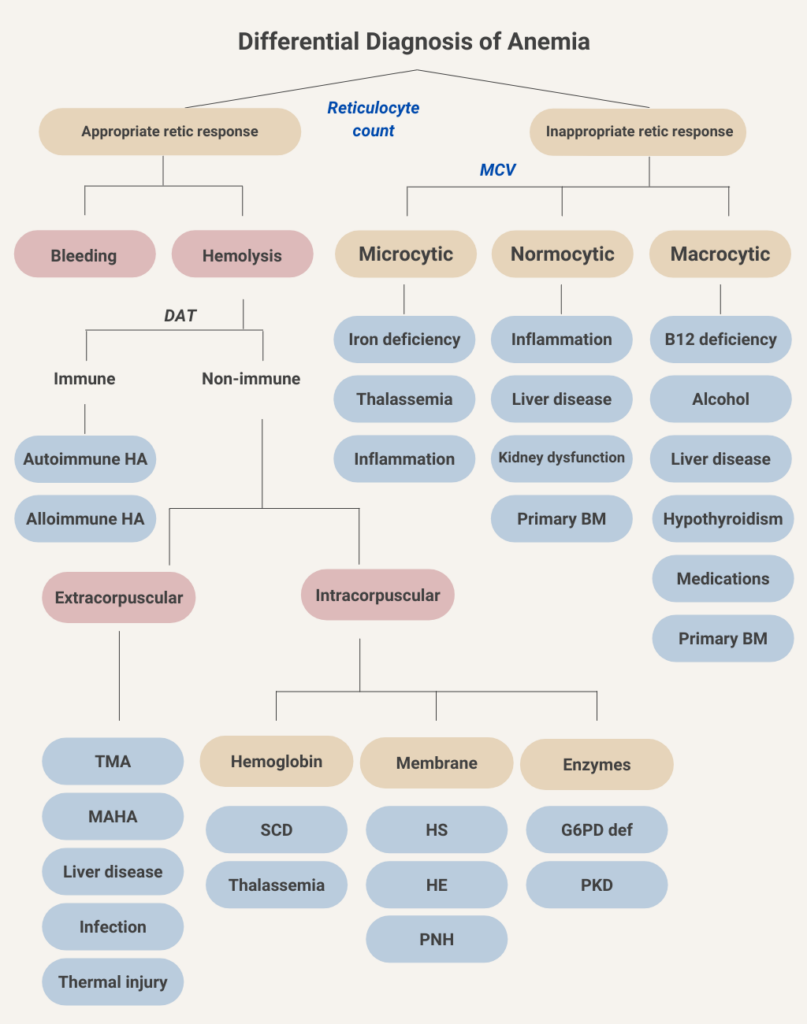

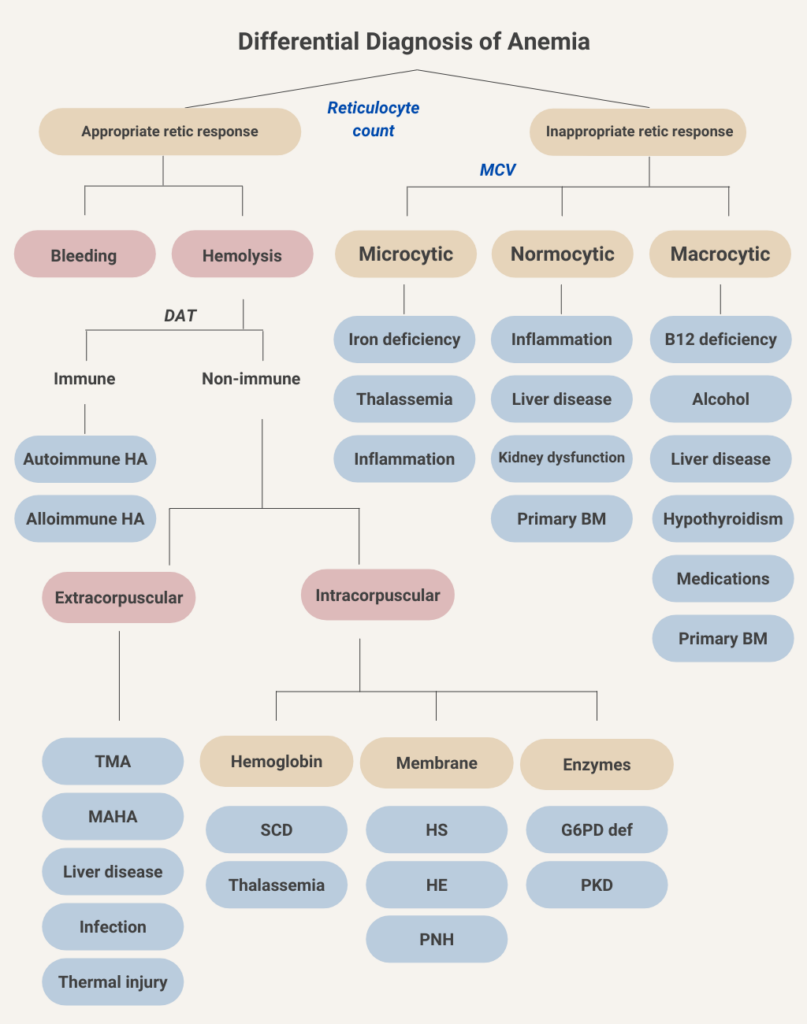

Let’s return to the first branch point in the flow chart for anemia and consider the causes of anemia associated with an inappropriate reticulocyte response (the so-called hypoproliferative anemias; upper right in above schematic).

What lab result is needed for the initial classification of hypoproliferative anemias?

Click for AnswerThe first branch point in considering hypoproliferative anemias is the mean cell volume (MCV). This represents the time-honored morphological classification of anemia and is very helpful when sorting through the differential diagnosis of anemia.

Let’s do another sorting exercise. In this case, drag the disease or condition into the appropriate red cell size bucket (the distinctions are not black and white – for example, hypothyroidism is classically associated with macrocytosis [which is the correct choice here], but in fact most such patients are normocytic).

So now the classification of anemia, based on kinetics (reticulocyte count) and morphology (mean cell volume). A second component of the morphological classification, which we have chosen not to include in order to keep things simple, is the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), which may be used to separate microcytic anemia into hypochromic (low MCHC) causes, as seen in iron deficiency anemia, and normochromic (normal MCHC) causes, which is more typical of thalassemia.

Time for another sorting exercise! This time, we are going to identify types of anemia that are typically associated with concomitant thrombocytopenia. Drag and drop the cause of anemia on the top cards into the appropriate bucket (associated with concomitant thrombocytopenia or not).

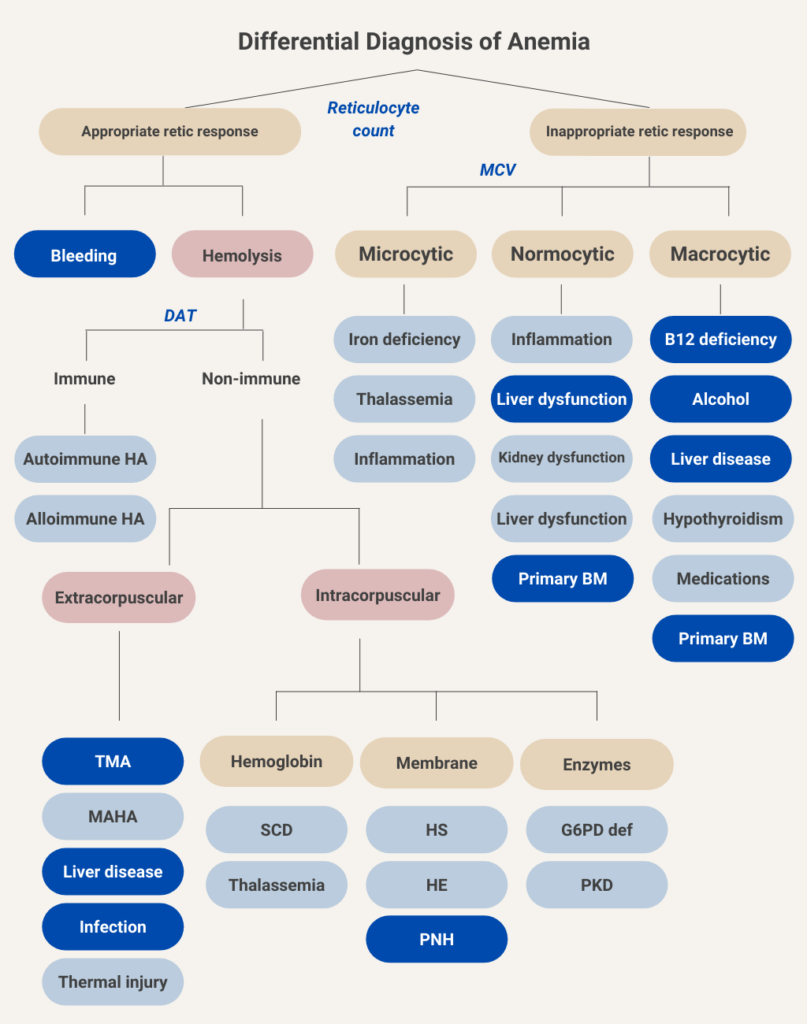

The following is the differential diagnosis for anemia, with those conditions associated with concomitant thrombocytopenia indicated in dark blue. We have included patients with bleeding because thrombocytopenia may cause of bleeding, and because massive transfusion may lead to dilutional thrombocytopenia. Although rare, patients with severe iron deficiency anemia may have low platelet counts (not shown), and those with autoimmune hemolytic anemia may have concomitant immune thrombocytopenia (Evans syndrome, also now shown).

Below, we have reorganized the diagnostic algorithm for anemia in table format according to those conditions associated with concomitant thrombocytopenia (TP):

| Category | Cause of anemia | Cause of TP | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding | Blood loss | Any cause of TP | TP increases risk of bleeding and may be caused by massive transfusion in a patient with hemorrhage. |

| Hemolysis | |||

| AIHA | Immune-mediated red cell destruction | ITP – immune mediated platelet destruction | Combined AIHA and ITP is called Evans syndrome. |

| TMA | Microangiopathic hemolysis | Consumption | TP is part of the disease spectrum. |

| Clostridial sepsis | Intravascular hemolysis | Consumption | TP is common in all types of sepsis. |

| Babesiosis | Intravascular hemolysis | Unclear mechanism | TP is a common finding in babesiosis. |

| Cirrhosis | Spur cell anemia, hypersplenism | Hypersplenism | TP is the most common cytopenia in cirrhosis. |

| PNH (membranopathy) | Intravascular hemolysis, marrow suppression | Marrow suppression | TP is common in PNH. |

| Normocytic anemia | |||

| Primary bone marrow process | Marrow suppression | Marrow suppression | Myelodysplasia, aplastic anemia, plasma cell dyscrasia, and leukemia may all cause TP. |

| Macrocytic anemia | |||

| Alcohol | Marrow suppression | Marrow suppression | TP is more common than anemia with alcohol toxicity. |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency | Ineffective erythropoiesis | Marrow suppression | TP and leukopenia may both occur. |

Recall from the history that the patient’s complete blood count (CBC) was normal just three months ago. This piece of information helps us narrow the differential diagnosis. For example, it is unlikely that vitamin B12 deficiency and many of the more chronic causes of primary bone marrow failure would present in such a precipitous manner. In fact, the timing of the anemia and thrombocytopenia helps us narrow the likely diagnosis to:

- Acute primary bone marrow process (for example, acute leukemia)

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and ITP (Evans syndrome)

- Thrombotic microangiopathy:

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Infection

- Babesiosis

- Clostridial sepsis (though the presentation is usually more dramatic)

You should be a pro by now: what lab test would help you separate hemolytic from non-hemolytic causes of anemia?

Click for AnswerWhat conditions are associated with an elevated reticulocyte count?

What conditions are associated with an elevated reticulocyte count?

Let’s consider the differential diagnosis of recent/new onset thrombocytopenia and anemia. What would you expect the reticulocyte count to be in each case – appropriately increased or inappropriately low (answer on next slide)?

| Disease | Reticulocyte count |

|---|---|

| ITP with major bleed or Evans syndrome | |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura | |

| Primary bone marrow conditions | |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | |

| Babesiosis |

Let’s return to our differential diagnosis of recent/new onset thrombocytopenia and anemia. What would you expect the reticulocyte count to be in each case – appropriately increased or inappropriately low (answer on next slide)?

| Disease | Reticulocyte count |

|---|---|

| ITP with major bleed or Evans syndrome | Appropriate |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura | Appropriate |

| Primary bone marrow conditions | Inappropriate |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | Appropriate |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | Appropriate |

| Babesiosis | Appropriate |

Keep in mind that an appropriate reticulocyte response assumes that the bone marrow is able to make more red cells. If there is a concomitant condition, for example iron deficiency or inflammation, that suppresses erythropoiesis, the patient may not be able to mount an appropriate reticulocyte count even in the face of severe hemolysis or bleeding.

W

Let’s look at the reticulocyte count in our patient:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Percentage reticulocytes | 4.5% |

| Absolute reticulocyte count | 0.13 x 1012/L |

What is the patient’s red cell count in trillions (1012)/L?

Correct! 4.5% x [2.89 x 1012/L] = 0.13 x 1012/L

Returning to our differential diagnosis of newly diagnosed thrombocytopenia and anemia in an acutely ill patient, we can eliminate primary bone marrow disorders on account of the patient’s reticulocyte response.

| Disease | Reticulocyte count |

|---|---|

| ITP with major bleed or Evans syndrome | Appropriate |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura | Appropriate |

| Primary bone marrow conditions | Inappropriate |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | Appropriate |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | Appropriate |

| Babesiosis | Appropriate |

Let’s look at the various markers of hemolysis when the patient first presented to the emergency room:

| Parameter | Value | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| LDH | 2112 IU/L | 94-250 IU/L |

| AST/ALT | 71/30 IU/L | 0-40 IU/L for both |

| Haptoglobin | < 10 mg/dL | 30-200 mg/dL |

| Bilirubin (total) | 3.6 mg/dL | 0-1.5 mg/dL |

In summary, the above results are classic for hemolysis!

Interim summary

This is a 56 year-old man with recent/new onset anemia and thrombocytopenia associated with increased reticulocytes and positive hemolytic markers. Based on these data, we are thinking about Evans syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP), Babesiosis or other thrombotic microangiopathies such as hemolytic uremic syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation. The elephant in the room, which we are ignoring for the moment, is the change in mental status. This drives TTP to the top of the differential diagnosis. But let’s play along and put the neurological findings aside for a moment.

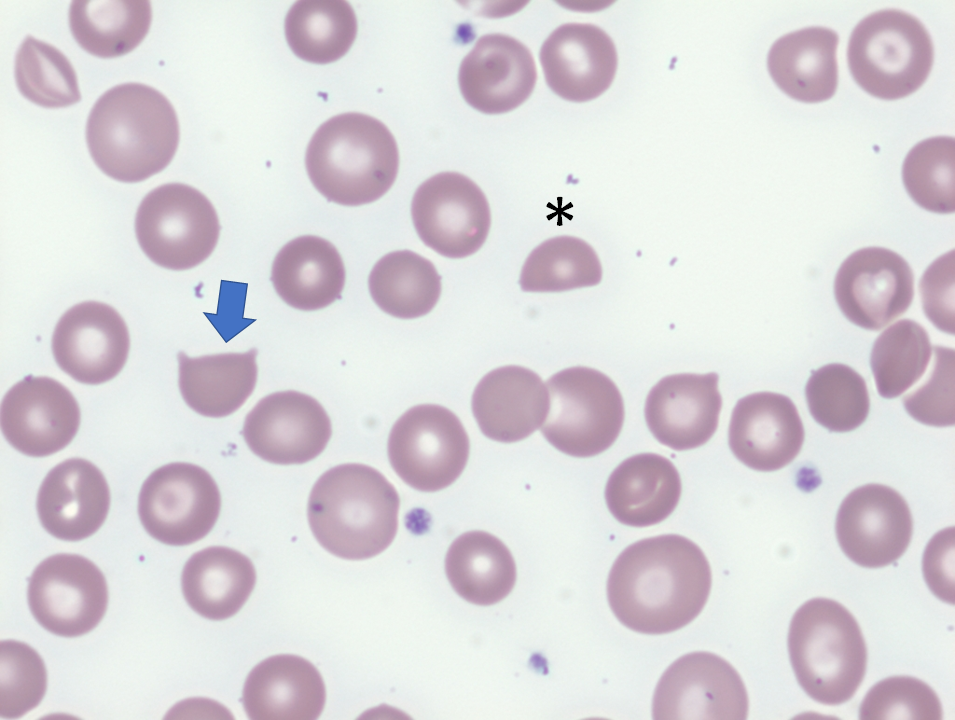

Now it’s time to consider the peripheral smear. In addition to low platelet numbers, what findings would you expect to see in the 4 conditions under consideration (answer on next slide)?

| Condition | Peripheral smear findings |

|---|---|

| Evans syndrome | |

| TTP | |

| HUS | |

| DIC | |

| Babesiosis |

Now it’s time to consider the peripheral smear. In addition to low platelet numbers, what findings would you expect to see in the 4 conditions under consideration (answer on next slide)?

| Condition | Peripheral smear findings |

|---|---|

| Evans syndrome | Polychromatophilia, spherocytosis |

| TTP | Polychromatophilia, schistocytes |

| HUS | Polychromatophilia, schistocytes |

| DIC | Polychromatophilia, schistocytes |

| Babesiosis | Polychromatophilia, intraerythrocytic inclusions |

The peripheral smear from the patient is shown here:

For more information about schistocytes, click here.

The patient’s direct antiglobulin test (DAT) was negative.

The combination of appropriately elevated reticulocytes, positive hemolytic makers and negative DAT places him in the extracorpuscular hemolytic anemia “bucket”. The presence of schistocytes on the peripheral smear further narrows the diagnosis to thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), which may be caused by thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura, hemolytic uremic syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation or a handful of other secondary causes (see next slide),

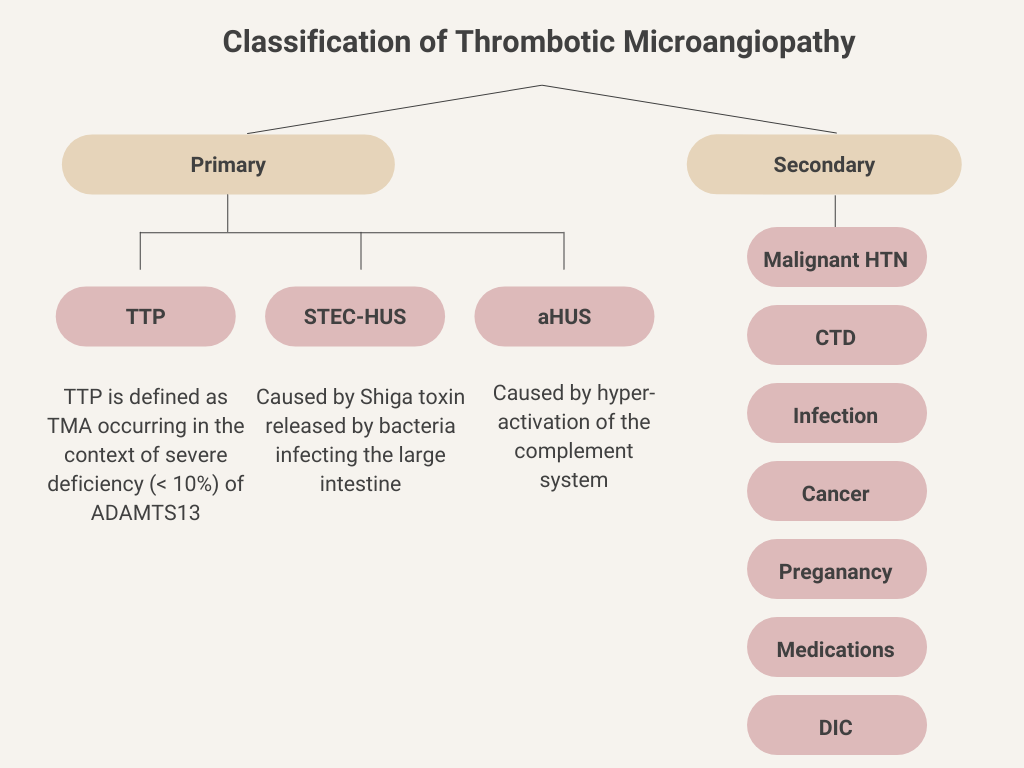

Let’s consider the thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs) for a moment.

Definition: TMAs are a group of rare disorders characterized by thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), and microvascular thrombus formation (fibrin/platelet rich), leading to tissue injury. MAHA, in turn, is characterized by red blood cell destruction within the microvasculature accompanied by thrombocytopenia due to platelet activation and consumption.

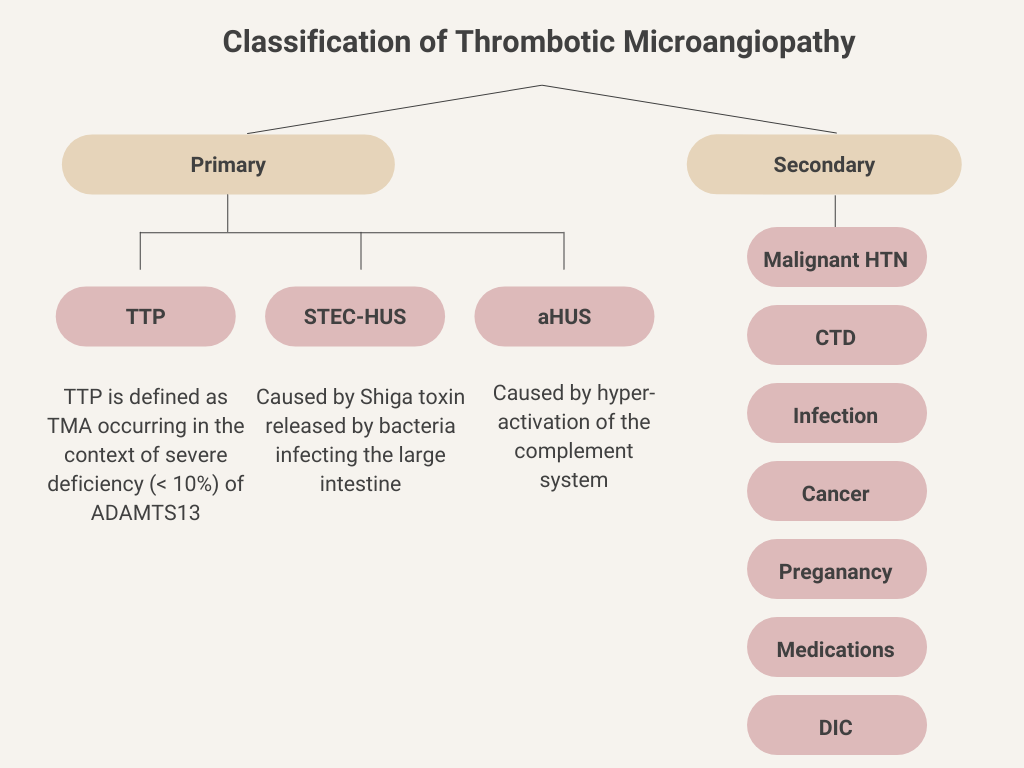

Classification: TMAs may be classified as primary or secondary. Primary TMAs occur spontaneously with no associated underlying cause, and include thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). Secondary TMAs are associated with an underlying condition.

What tests would be most helpful in distinguishing between thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS)?

The patient’s BUN and creatinine were normal. Thus, a diagnosis of hemolytic uremic syndrome is unlikely.

What tests would be most helpful in distinguishing between thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP) disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)?

The fibrinogen and prothrombin times were normal in this case. The ISTH has developed a scoring system for the diagnosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). For starters, it is necessary to identify an underlying condition that causes DIC, and that is not apparent in this patient, making a diagnosis of DIC unlikely to begin with. Next, the following lab parameters are considered:

| Parameter | Score | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | >1 (0) <1 (1) | Overall sensitivity of low fibrinogen level reported to be about 30%. |

| Prothrombin time (PT) (seconds) | <3 (0) 3-6 (+1) >6 (+2) | Elevated in 50%-60% of patients with DIC at some point during course of illness. |

| Platelet count (x 109/L) | >100 (0) 50-100 (+1) <50 (+2) | Thrombocytopenia reported to occur in up to 98% of DIC cases. |

| D-dimers or FDPs | No increase (0) Moderate increase (+2) Severe increase (+3) | Elevated FDPs and D-dimers are sensitive, but not specific for DIC. |

Data are presented as values with number of points in parentheses.

A total score of ≥5 is compatible with diagnosis of DIC

This patient did not have D-dimers or FDPs measured. So, he could technically have made the cut for DIC if he had a severe increase in D-dimers or FDPs (for a total of 5 points). However, the absence of an identifiable underlying condition makes this all but a moot point.

By a process of elimination – even in the absence of a history or physical exam – we arrive at thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP) as the most likely diagnosis (red color indicates the results found in the patient):

| Disease | Reticulocyte count | Schistocytes | Renal function | Fibrinogen/PT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITP with major bleed or Evans syndrome | Appropriate | No | Normal | Normal |

| TTP | Appropriate | Yes | Normal | Normal |

| Primary bone marrow conditions | Inappropriate | No | Normal | Normal |

| HUS | Appropriate | Yes | Abnormal | Normal |

| DIC | Appropriate | Yes | Normal | Low |

| Babesiosis | Appropriate | No | Normal | Normal |

… add in the neurological changes, and the pretest probability of TTP further increases.

Is there a diagnostic test for ITP?

Is there a single diagnostic test for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)?

What is ADAMTS13?

What is ADAMTS13?

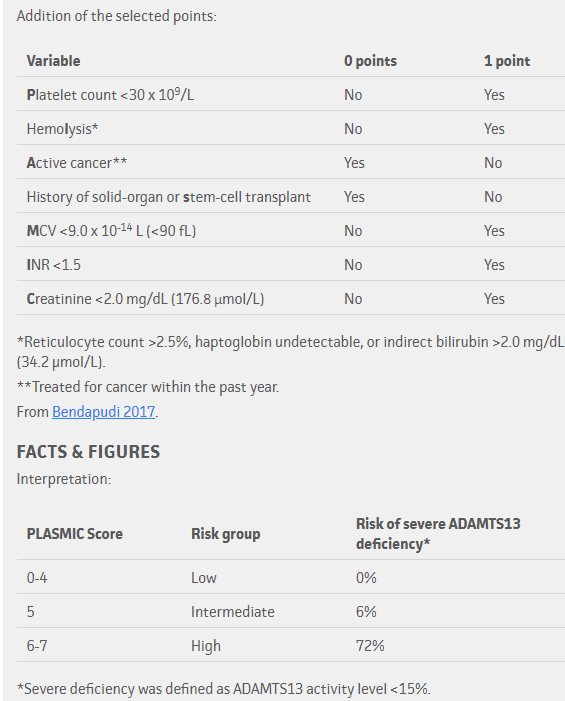

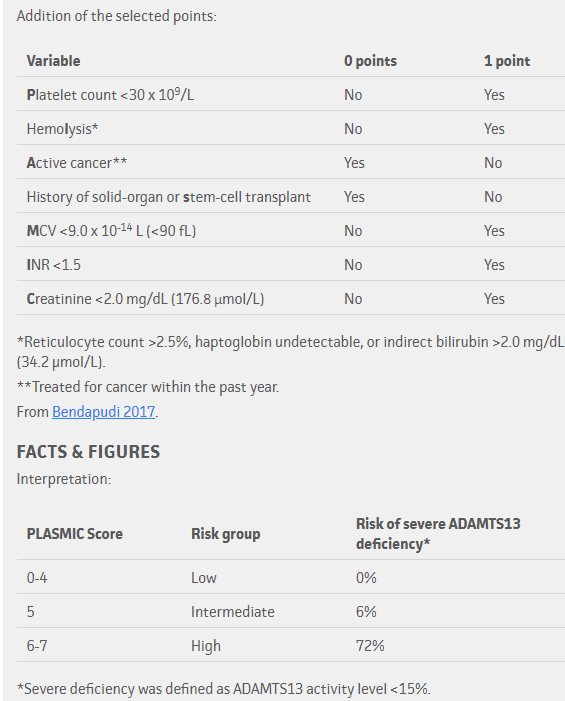

The ADMATS13 is a send-out test. The initial diagnosis of thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP) must be made without the benefit the ADAMTS13 level, which typically takes several days to come back. One can either use their clinical experience to determine who is at high risk for the condition or use a clinical prediction score for TTP. One of these is called the PLASMIC score. Let’s see how it works on the next slide.

PLASMIC score

Notes:

- The higher the score, the greater the likelihood of TTP.

- Many of the parameters included in the PLASMIC score are negative predictors of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). For example, the score takes into consideration non-TTP thrombotic microangiopathy caused by transplantation and cancer (based on history), disseminated intravascular coagulation (based on an elevated INR) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (based on elevated creatinine).

- Schistocytes are not included in the score because they are considered a precondition for applying the score.

- The PLASMIC score was developed using a cohort of 214 patients with suspected thrombotic microangiopathy and has been validated in 2 additional cohorts of patients.

Our patient’s platelet count of 11 x 109/L qualifies for one point. He also gets one point for the unmistakable finding of hemolysis, and another point each for not having a history of cancer or solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. That’s four points so far. Add another point for the normal PT/INR and we are up to a total of five points. The patient’s mean cell volume (MCV) was < 90 fL for another point. Finally, the creatinine was normal, bringing the tally to seven points for a pretest probability of about 70%.

What is the explanation for a low MCV (one of the PLASMIC criteria) in TTP?

What is the explanation for a low mean cell volume (one of the PLASMIC criteria) in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)?

Some final thoughts about diagnosing thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), including thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP):

Any time a patient presents to urgent care with new onset of anemia and thrombocytopenia, we must consider thrombotic microangiopathy, especially TTP and atypical hemolytic uremia syndrome, because these conditions, if left undiagnosed and untreated, have high mortality. As hematologists, we are trained to use pattern recognition to identify patients with this condition, and the patient in this case would be no exception: new anemia, thrombocytopenia and mental status changes = TMA until proven otherwise. A quick look at the reticulocyte count, the DAT, the hemolysis indices and the peripheral smear, and the diagnosis is clinched within an hour of seeing the patient. That being said, it is always important to cross-check real time data with conceptually sound diagnostic frameworks – like the flow charts and algorithms shown in this case study – and to constantly update your assessment accordingly. The purpose of this exercises in this case study is not to slow you down at the bedside, but rather to help you build enduring conceptual frameworks with which to approach diagnosis.

Before moving on to treatment, let’s consider the full panel of tests we might order in a patient with suspected thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). The following are recommendations by the British Committee for Standards in Haematology (see clinical practice guideline) in such patients:

| Test | Comments |

|---|---|

| Complete blood count | Anaemia, thrombocytopenia |

| Peripheral smear | Schistocytes |

| Reticulocyte count | Increased |

| Haptoglobin | Reduced |

| Clotting screen including fibrinogen | Normal |

| Urea and electrolytes | +/- Renal impairment |

| Troponin T/Troponin I | For cardiac involvement |

| Liver function tests | Usually normal |

| Calcium | May reduce with TPE |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | Increased |

| Direct antiglobulin test | Negative |

| Blood group and antibody screen | To allow provision of blood products |

| Pregnancy test | In women of child-bearing age |

| ADAMTS 13 assay ((activity/antigen and inhibitor/antibody in specialized laboratory) | Do not wait for result before starting treatment in suspected TTP |

| Electrocardiogram/Echocardiogram | To document/monitor cardiac damage |

| CT/MRI brain | To determine neurological involvement |

Should the patient be admitted to the hospital?

The patient is admitted directly to the hospital