Introduction

Just as blood itself is fundamental to biological functioning, the concept of blood is fundamental to human culture. From linguistics to art to spirituality and religion, blood flows through collective consciousness across history, shifting and changing in context, but always meaning something to us. In this essay, we ask what does blood symbolize, beyond its role in medicine? What functions does it serve socially, culturally, and politically?

We will begin with prehistoric times, when blood was seen as a life-force, at once revered and feared. We will see that prehistoric man does not distinguish between medicine, magic and religion, and that blood as entity and concept breaches each of these boundaries. From this cultural cauldron emerged a number of stereotypic blood rituals, including blood sacrifice, bloodletting, blood consumption and blood taboos, which were collectively designed to appease the gods and to provide the common man with strength, vitality and protection. Remarkably, these practices, which we will discuss in turn, arose independently over and over again in different populations around the world, separated by thousands of years, suggesting a kind of innate universalism in our reckoning with this mysterious red fluid.

Modern medicine, for all its advances, has done little to quell our uneasy – and often irrational – relationship with blood. When a nurse or phlebotomist draws blood from my arm, I am sure to turn my gaze. Otherwise I become queasy watching my own blood pour into a vacutainer. Not everyone does, but I know I am not alone. Why should we be distraught at the sight of our own blood? We have all experienced nosebleeds before. In most cases, we regard the occurrence as a mere annoyance. However, if the bleeding is heavy, we may become frightened. Although epistaxis (a medical term for nosebleed) is rarely a matter of life and death, there is something about spilled blood, especially when it’s our own, that evokes a sense of horror, an emotion that resides deep within the brain’s amygdala, most certainly shared with our earliest ancestors.

As we will discuss, the fear of blood (or is it awe?) can be overridden by certain powerful societal and cultural forces. How else can we explain parents attending circumcision ceremonies in the Jewish religion (faith over fear of blood), partners providing support during childbirth (love and commitment over fear of blood), those who attend a tattoo parlor or piercing shop (pursuit of self-expression over fear of blood), and blood donors who lose up to half a liter of blood in one sitting (goodwill over fear of blood)? The loss of blood during war is often considered a noble venture, if not by the fallen, then certainly by the leaders of nations. We commemorate these brave soldiers by attaching a blood-red poppy to our lapel every year.

And we can always play out our visceral horror of blood in the safety of our stadium seats, theaters and living rooms. Whether through the gladiator fights of Ancient Rome, the cockfights of past and present, the Broad Street Bullies of the 1970s (the infamous Philadelphia Flyers of the National Hockey League who, in the 1970s, “spilled enough blood to fill a decade’s worth of Stanley Cups”)1, or modern-day mixed martial arts, we have set up the rules so that we can engage with blood without having to sacrifice a single drop of our own. Some of us welcome, indeed even relish, such opportunities. Others are more likely to recoil and avoid such scenes altogether.

There is no shortage of television shows and movies on vampires, not to mention films of the Gothic horror genre. When we watch these offerings, we may experience intense emotions. As history has taught us, some of these reactions are undoubtedly hard-wired and shared between most viewers. Other reactions are shaped by individual life histories, and in this way are highly subjective. That’s the wonder of blood: it is universal yet so deeply personal.

Blood magic

The concept of blood has held our collective fixation since the earliest humans recognized that uncontrolled bleeding at the hands of an animal predator or an enemy tribe spelled certain death. To prehistoric humans, blood was observed to flow when a wound was opened and to stop flowing when life was gone, no matter the cause of death. In a world driven by incomprehensible forces, yet to be probed and mapped by modern science, blood was held in evidence to be equivalent to life itself.

There is no evidence of medicine until the Neolithic period, about 7,000-10,000 years ago, when prehistoric humans exchanged their food-gathering ways for a life of agriculture. Even then, medicine was inseparable from magico-religious ideas. Neolithic peoples saw danger everywhere: they were surrounded by hostile forces, and lived on constant guard against disease-causing ghosts, spirits, deities and sorcerers. A man felled by the spell of a sorcerer was the target of another man’s wrath, or magic. When illness arose from a supernatural agency, a religious explanation was in order. “We must remember,” writes Henry Sigerist (1891-1957), a renowned Swiss medical historian, “that the primitive does not distinguish between medicine, magic and religion… to him they are one, a set of practices intended to protect him against evil forces and to bring him good luck.”3

In keeping with this trend, the earliest recorded engagements with blood as concept and substance interweave spirituality, ritualism, and prehistoric medicine. Neolithic peoples could see blood, smell it, taste it and feel it. They could watch it pour out of a wound until an animal went cold, but they had no idea what its true purpose was. Such knowledge would elude humankind for the next several thousand years. What they saw was an animating life force that could be leveraged for magical and religious purposes to appease the gods and win favor with or punish their fellow tribesmen. Writing about prehistoric man, Bernard Seeman concluded that “Our knowledge of blood has been colored by magical concepts often disguised as philosophy, theology or science… the greatest offering man could make to the demons of his shadowy world was the gift of blood.”4

Blood sacrifices

Ritualized blood offerings as both spiritual practice and early medicine permeate anthropological data across disparate geographic regions, reflecting the near-universalism of blood as spiritual symbol and ritual tool. In the Neolithic period, people who lived by tilling the soil routinely offered up blood sacrifices in preparation for the spring harvest.5

The Aztecs, a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico between 1300 and 1519 AD, were known to use blood and sacrifice (including humans) as offerings to the Sun God.6 They were reported to have sliced out the hearts of victims and spill their blood on temple altars. Such ritual killings and sacrifice of blood served to appease the Sun God, and to remind enemies of the strength of the empire.7

The Maya, another rich culture indigenous to modern Mexico, incorporated ceremonial blood-drawing, self-mutilation and auto-sacrifice in their spiritual practice. Describing 16th century Maya civilization, Diego de Landa writes:

They offered sacrifices of their own blood, sometimes cutting themselves around in pieces and they left them in this way as a sign. Other times they pierced their cheeks, at others their lower lips. Sometimes they scarify certain parts of their bodies, at others they pierced their tongues in a slanting direction from side to side and passed bits of straw through the holes with horrible suffering; others slit the superfluous part of the virile member leaving it as they did their ears.8

Half a world away, the Vikings made frequent blood and animal sacrifices to keep on good terms with the gods. They chose dedicated sacrificial sites where they believed they would have the strongest contact with the gods. In the 13th century, horses were the preferred sacrificial animal. They were made to bleed into bowls, and twigs were then used to paint the altars, walls and ritual participants with blood.9

Today, ritual bloodletting continues in certain parts of the world. During the festival of Ashura in Kabul, Shi’ite participants enact ritualized penitence and colorful celebration in memory of Imam Hussain, the Prophet Muhammad’s grandson who was killed in a battle in 680 AD.10 During the last day of the festival, participants are whipped with flails tipped with razor-sharp blades. Aryn Baker, who wrote an essay on this ritual in Time Magazine, quoted a local participant: “Our imam was killed, his blood was shed for Islam, so we shed our blood for Islam.”11

To this day, different ethnic groups from Ghana travel to the shrine and dwelling place of the West African deity Tongnaab, near the remote northern village of Tengzug, to consult with the deity. These worshipers bring chickens, goats, sheep, donkeys, cows, and even dogs to sacrifice—offerings to curry favor in their search for fertility, stability, prosperity, and security in life. Others sacrifice to make amends for evil acts and to reverse the negative consequences of sin or curse. The spirits in the shrines are believed to feed off the life-blood of animals, so requests made for help and atonement must be accompanied by sacrifice. Jawbones and skulls of sacrificed animals are often displayed to show the number of sacrifices a person has performed or to demonstrate the power of a particular shrine.12

Contemporary circumcision is an outgrowth of prehistoric blood sacrifice, in which the firstborn son was sometimes offered as a sacrifice, possibly for continued fertility.13 In the Jewish faith, circumcision is sometimes referred to as the covenant of Abraham, who circumcised himself in order to become a Jew. Today, Orthodox and Conservative Jews still practice circumcision or, in adults, a ritual reenactment called hatafat dam brit, in which the mohel (circumciser) pricks the skin around the glans penis with a hypodermic needle or a lancet and collects the blood on a gauze pad, which is then shown to three witnesses.14 Through this practice, the adult convert is accepted into the Jewish faith. In a New York Times article, Jeffrey Rosen describes a male circumcision ritual practiced by some Hasidic Jews in New York: “The ritual is called oral suction, or metzitzah b’peh. After removing the foreskin, the mohel, who conducts the circumcision, cleans the wound by sucking blood from it.”15

The shedding of blood in ritual sacrifice spans thousands of years. Whether the offering is embedded in magico-religious beliefs or is carried out as a purely symbolic gesture, it has withstood the test of time as a powerful cultural motif.

Bloodletting

Blood removal has played a prominent role in magico-religious-medical practice since the dawn of mankind. “Bleeding,” wrote the historian Erwin Ackerknecht, “is an almost universal trait in primitive medicine.”16 In Mexico, prehistoric hunters and gatherers left evidence of ritual bloodletting in a small well-hidden cave named Cuevo Pilote. Prehistoric tribes across South America used venesection (bloodletting by cutting a vein) or scarification (bleeding by creating scratches in the skin) to drive out a spirit, which escaped with the blood that flowed.17 The ancient Maya practiced sacrificial bloodletting to communicate with their dead ancestors and their gods.18 When Ancient Egyptians slaughtered a cow or an ox, they would lay it on its back and cut the arteries of its throat with a metal knife. Its blood was collected and examined to make sure that the animal was not possessed by a spirit.19

Bloodletting would become a therapeutic panacea from the early centuries BC to the 1800s. It was believed to restore humoral balance, a system of physiology that was codified by Galen in the 1st century AD and promulgated by the Church over the following 17 centuries. Bloodletting gradually fell out of favor as Galen’s system of humors gave way to an understanding of the circulation as a closed system with limiting quantities of recycled blood. Today, bloodletting is still practiced by tribes around the world on magico-religious grounds, while Western medicine leverages bloodletting for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

A modern-day form of bloodletting is also seen with the practice of self-cutting. This mode of self-injury is often described as a coping strategy to deal with overwhelming feelings or experiences of dissociation.20 Sociological enquiries have shown that self-injurers place high value on the sight of their blood. A participant in one study was quoted as saying, “I loved the sight of my own blood seeping out of fresh wounds.”21 The study’s author explains that “Looking at blood is perceived as exhilarating or fascinating, comforting or calming.”22 It symbolizes to the self-injurer that they are alive, vital and real. Reminiscent of ancient bloodletting, today’s self-cutter often feels their inner pain and fear flow outwards with their blood.

Blood meals

The fusion of ritualism and ancient medicine involved “treatments” and cures that we now know to be symbolic, but which seemed clinically sound (and why not?). For some early humans, blood was viewed as a source of strength (a life force) to be consumed for its vitality. The blood of a mammoth might provide strength, while that of a hawk might sharpen vision. When a warrior of ancient Scythia killed his first opponent in battle, he drank his victim’s blood to gain strength from the life-giving fluid.23

In Rome during the early centuries AD, country-folk who practiced self-help medicine were said to treat epilepsy by drinking the blood of a gladiator whose throat had been slit.24 Certain tribes indigenous to New South Wales would feed the sick with raw or slightly cooked blood drawn from their male friends, who willingly bled themselves for the sake of the patient.25

The consumption of blood as food and drink continues to this day. The Maasai, a pastoralist people living primarily in southern Kenya and northern Tanzani, traditionally live off a diet of beef, milk, and blood.26 Beyond its dietary function, the mixture of blood and milk is also used as a ritual drink for special celebrations and for healing the sick.27 Maasai tradition also involves giving blood to drunken elders to alleviate intoxication and hangover.

Readers who have travelled to the British Isles may have tried black sausage, made with blood from pigs and cows and recommended for those on a shoe-string budget because blood is an inexpensive ingredient.

And then, of course, there are the vampires, so frequently represented in popular culture. Vampire folklore began with Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897. Today, there is no shortage of vampiric television offerings: The Vampire Diaries, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and True Blood, to name just a few. A common theme in these shows is the fictional vampire’s dependency on blood as an essential life force.

Vampires are not merely figments of our imagination. The annals of true crime attest to the occasional deranged killer caught up in some twisted vampiric roleplaying. On top of that, there are scattered, peaceful blood-feeding communities in the United States, and perhaps elsewhere around the world. In a fascinating piece by David Robson for the BBC in 2015, one such group in New Orleans was uncovered. They are an eclectic bunch, bound together by a common “need” to drink blood. He describes a donor-vampire pair engaged in a “feeding”:

It begins as clinically as a medical procedure. His acquaintance first swabs a small patch on Browning’s upper back with alcohol [Browning being the name of the blood donor]. He then punctures it with a disposable hobby scalpel, and squeezes until the blood starts flowing. Lowering his lips to the wound, Browning’s associate now starts lapping up the wine-dark liquid.28

We learn that donors, who are hard to come by, can at least choose whether the blood is collected from a cut with a scalpel, or intravenously with a cannula or butterfly needle.

While blood feeding practices span thousands of years, their justification and rationale should be considered in the context of the times. Before the discovery of the circulation and the unraveling of humoralism, blood was widely seen to contain spirits – good and bad – that could be passed on to the consumer. Blood meals made perfect sense, if only you could find a source with the desired spiritual mix. Today, of course, we understand that blood, when ingested, is no greater than the sum of its nutritional parts and that its consumption is more likely to reflect a dietary preference or a ritualistic practice.

Blood taboos

Rules of avoidance – or taboos – are among the oldest of unwritten code of laws.29 Taboos are designed to protect against terrible consequences. With blood’s intimate connection to life and death, and its seeming potency as a magical force, there have been occasions where blood was viewed not as a positive life force, but instead as an evil force to be reckoned with.

We noted earlier that prehistoric peoples drank blood as a source of vitality. Others avoided drinking blood because it contained unwanted qualities. So, while one prehistoric tribe might drink blood from a hawk to sharpen their vision, other tribes might place a taboo on such an activity out of fear they would be possessed by the hawk’s spirit.

Invocations of blood in mainstream religious doctrine include dietary taboos. The Jewish taboo against blood is clearly articulated in the Old Testament: “And whatsoever man there be of the children of Israel, or of the strangers that sojourn among you, which hunteth and catcheth any beast or fowl that may be eaten: he shall even pour out the blood thereof and cover it with dust” (Lev. 17:13). Islam also forbids the consumption of blood. In both Jewish and Islamic faiths, draining of blood from the animal is required before consumption of the meat (though not all followers adhere to these guidelines). Blood taboos are only one dimension of religious mobilization of blood imagery. We will discuss the centrality of blood symbolism in Christianity in the section on “Blood Covenant”.

Perhaps the most notable (and universal) of blood taboos has revolved around menses, that natural phenomenon perpetually shrouded in secrecy and fear. Prior to our understanding of the inter-connection between ovulation and menstruation in the 1800s, mystical explanations prevailed, the most common being that menstruation periodically rids the woman’s body of something undesirable that had accumulated in the blood. According to this view, menstruation is a process of purification. A more magical belief was that menstrual blood contained an evil spirit, which would then have the capacity to harm her environment. For this reason, women were isolated during their menstrual cycle. For example, in prehistoric times menstruating women were typically quarantined for fear that anything they touched or looked at might be destroyed. Women in the Kafir tribes of South Africa were secluded from the cattle and milk supply, while Galela women were not permitted to enter tobacco fields for fear of damaging the crop.30

Contemporary blood taboos related to menstruation continue to shape themselves around symbols of impurity and filth. Cultural responses to this symbolism often involve gestures of isolation and social exclusion during the period of menstruation. In an article about menstruation myths in modern day India, Garg and Anand review some of these practices, writing that in many Indian households, menstruating women are barred from entering the kitchen (preparing and handling food is strictly forbidden) and restricted from offering prayers and touching holy books for fear of contamination.31

In Nepal, menstruating women are traditionally banished to a specially built hut, often lacking a proper bed, until menstruation has ceased. During the period of menstruation, they are forbidden from touching plants, cattle, or men. Such taboos around menstruation have caught the attention of global health leaders, who recognize their negative impact on “women’s emotional state, mentality and lifestyle and most importantly, health.”32 Cultural symbolism that associates menstruation with impurity shapes the routines, identities, and power dynamics experienced by menstruating women within those cultures.

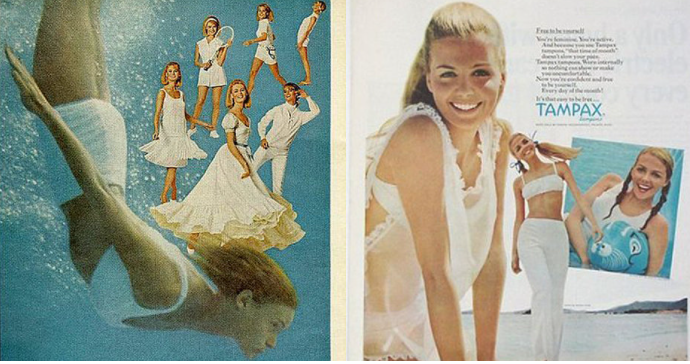

Discomfort with menstrual blood extends to Western cultures. When discussed, it is frequently characterized euphemistically as ‘that time of the month’. There is rarely explicit reference to blood itself. Advertisements for hygienic products have traditionally tiptoed around the concept of menstrual blood. Women are typically portrayed as fun-loving, physically active and dressed in white.

Interestingly, recent advertising campaigns have started to dismantle the taboo. For example, Kotex posted a new advertising campaign for pads featuring red liquid instead of the traditional blue. A company executive was quoted as saying: “Blood is blood. This is something that every woman has experienced, and there is nothing to hide.”33

Libra, a supplier of menstrual pads, launched a destigmatizing ad campaign in 2017 called Blood Normal.34 Not only did they show menstrual blood as red, but they did so on the inside of a woman’s thigh.

While blood taboos around menstruation are pervasive, the stigma of uncleanliness and disgust are particularly troublesome in women who cannot afford hygienic products. This situation, which has been labeled ‘period poverty’, leads to the use of unhygienic measures, such as paper towels, cardboard and toilet paper. Cultural shame associated with menstruation prevents these individuals from talking about their predicament.35 This is an example of how symbolic associations with blood may have material impact and supports the notion that symbols are important.

Seeman writes that blood taboos, as with blood magic, “must have arisen out of humanity’s relatively common response to a common need at a common level of cultural development”.36 That being said, the practice of blood consumption, which we discussed in the previous section, is antithetical to blood taboos and cautions against adopting a purely universalist interpretation of humankind’s cultural reaction to blood.

Blood covenant

With the development of organized religion in the early centuries BC, we see the consolidation of blood-related symbolism from disparate spiritual traditions into religious texts. This development is important in our tracing of cultural engagement with blood as substance and symbol. The advent of the printing press in the mid-15th century and the rise in literacy rates over ensuing years accelerated the dissemination of cultural ideas through language. Colonial violence and global expansion furthered the reach of ossifying notions of body, spirit, and symbol.

Blood is a pervasive Christian religious symbol. The Catholic Church holds that the blood of Jesus can cleanse us from all sin and that Christ’s shedding of blood at the Crucifixion represents the hope of salvation. The Bible mentions blood more than 400 times.37 In John 6:54 in the Bible, Jesus states: ”The man who eats my flesh and drinks my blood enjoys eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day.”38

The “blood” of Christ is mentioned in the writings of the New Testament nearly three times as often as the “Cross” of Christ, and five times more frequently than the “death” of Christ.39 The blood of Christ stands not for his death but rather for his life released through death.

Today, Christians take communion with the understanding that the cup of wine symbolizes Jesus’s blood. This is not unlike imitative magic practiced by prehistoric peoples. Some Roman Catholics even believe in transubstantiation, or the change of substance or essence by which the wine becomes in reality the blood of Jesus Christ.

Since the days of Jesus’s apostles in the 1st century, Christians have been directed to “abstain” and “keep” from blood.40 As mentioned above, both Jewish and Muslim doctrines forbid the consumption of blood. Kosher Jews adhere to the practice of draining blood from meat, both at the time of slaughter and through salting.41 Jehovah’s Witnesses traditionally implicate passages from both the Old and New Testaments in their refusal to receive blood transfusions, even when it means the difference between life and death.42

So, we see that religion, which until the emergence of modern medicine held sway over our views of blood as entity and concept – primarily through the promulgation of Galenism, but also by virtue of ritualization – continues to shape our cultural understanding of blood. As illustrated by the refusal of some Jehovah’s Witnesses to accept blood transfusions, such influence may have serious material consequences from a health standpoint.

Blood bonds

Blood has been used to cement relationships between individual members of society for centuries. Such transactions – typically carried out in the setting of a ceremony – are termed blood bonds or blood oaths. In 440 BC, Herodotus, an Ancient Greek historian, wrote:

Oaths among the Scyths are accompanied with the following ceremonies: a large earthen bowl is filled with wine, and the parties to the oath, wounding themselves slightly with a knife or an awl, drop some of their blood into the wine… lastly the two contracting parties drink each a draught from the blow.43

A blood oath was famously used to seal a pact among the leaders of seven Hungarian tribes in the 11th century. Participants cut their arms and let their blood spill into a chalice, sealing their status as blood brothers.44

The essence of the symbolism imbued in the practice of blood bonds persists in contemporary life. Blood oath ceremonies, which involve two or more people pressing together small cuts (generally on a finger, hand, or forearm), represent the idea that each person’s blood now flows in the other participant or participants’ veins.

Blood oaths establish people who are unrelated by birth as “blood brothers” or “blood sisters.” They appear in contemporary culture in a range of contexts. For example, blood oaths are used in initiation rituals in the Mafia, as well as in prison gangs.

There are variations on the theme of a blood oath. Consider, for example, the blood vial that was popularized by Angelina Jolie and Billy Bob Thornton. The actors each wore a necklace containing each other’s blood. “She thought it would be interesting and romantic”, said Thornton, “if we took a little razorblade and sliced our fingers, smeared a little blood on these lockets and you wear it around your neck just like you wear your son or daughter’s baby hair in one”.45

Lest others wish to follow suit, they can order their own vial necklaces online. Why would you choose to go this route? Well, they inform us, “to carry your lover’s blood is said to create a bond between two souls”.46 The vials and necklaces are purchased as part of a kit, which also contains a full set of medical supplies for drawing a few drops of blood. It even includes medical grade anticoagulant to keep the blood in liquid form!

Popular culture is rife with linguistic invocations of blood and oath, whether in the form of blood oaths, blood brothers, or blood pacts. They have been featured in numerous television shows and movies including Game of Thrones, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, The Andy Griffith Show, Punky Brewster Malcolm in the Middle, Star Trek, The Hangover, and The Lord of the Rings. The pervasiveness of imagery related to blood as ritual connector reflects the ongoing potency of this symbolism.

Blood red

The mobilization of the color red as a symbol of vitality and magical powers can be traced back to the paleolithic period, with burial customs calling for the use of ochre as a symbol of life-giving blood.47 A symbolic link between blood and red – both essential and timeless – finds expression in practices, rituals and symbols such as power, love, vigor, and beauty.

Prehistoric man painted bodies of the sick and dead the color red using ochre, likely in an effort to provide them with life force. Red was also used in prehistoric art, evidenced by traces found in caves across the world.48 In signifying blood, red – for example, in the form of jewelry or clothing – has symbolized love and fidelity for centuries. Red, symbolic of the blood of Christ, features prominently in Christianity, including the red robes worn by Cardinals.

With blood as its essential and organic signified, the color red continues to carry symbolic currency in mainstream contemporary culture. “New” trends, rituals, and practices engage red in gestures of vitality, danger, and remembrance.

In advertising, the color red is used to convey sensuality, desire, love, vitality, strength, power and danger.49 Research has shown that red, relative to other achromatic and chromatic colors, leads men to view women as more attractive and more sexually desirable.50 The extent to which the red-attraction or red-sex links are related to blood imagery and whether or not these connections are culturally conditioned or genetically programmed is unknown.

Nonetheless, modern day lipstick manufacturers have leveraged these concepts to advertise and display their red lipstick with great pride, if not guilty pleasure. One such brand is called Forbidden Lipstick: Written in blood, “the most perfect blood red lipstick we’ve ever found“.51 Another company markets a red lipstick for “its blood-red vitality”.52

In signifying blood, red makes us think of war and by extension sacrifice, danger and courage. Blood-red poppies, mentioned in the Introduction, have a long association with Remembrance Day. They are worn on lapels as a memorial, representing the sacrifice of the fallen soldiers in past wars. They are also presented on graves in the form of wreaths.

The symbolism of red, then, is highly context dependent. A parishioner may be spiritually enriched by the red robes of the clergy, whereas the same man may be aroused by the red lipstick of his partner. When Remembrance Day comes around, he may be surrounded on the streets by red poppies that conjure images of bravery and sacrifice in ways that a purple or back colored poppy would simply not evoke. And of course, whatever responses I have to the red color in these three scenarios may well be quite different from yours.

Blood language

The history of blood has seen no shortage of irrational ideas about its larger meaning. While modern science has laid to rest many of the folk theories and superstitions about blood (blood lore), they continue to permeate society, influencing our customs and language. Our everyday language is riddled with references to blood: hot-blooded, cold-blooded, bloodcurdling, bad blood, blue blood, bloodline, lifeblood, bloodbath, fresh blood, bloodthirsty, blood sport, blood money, bloodcurdling, half-blood, young bloods, blood feud, and bloodlust to name just a few examples.

In some cases, blood is used as a metaphor for language and emotions. Consider, for example, the following sentence, which draws on an analogy between blood and language: “Language is the blood of the soul into which thoughts run and out of which they grow”.53 Or the idea that blood running cold is related to fear, and boiling blood to anger.54 In other cases, the word blood is incorporated into terms (many examples are listed in the previous paragraph) used in reference to the qualities of a person, or a group of individuals.55 The interpretation and contextualization of these and other blood metaphors is highly language-dependent and varies between different societies.

There are potent associations between blood, identity and social relations. Keith Waloo, an historian from Princeton University, points out in his book Drawing Blood that blood is a “rich symbol of individual identity, social health and group relations.”56 Before the discovery of genetics, it was widely believed that blood carried the essence of the individual, the family, the race and the nation. Blood was believed to hold the soul of an individual and perpetuate special qualities. The intersection of symbolism, racism, and (pseudo-)science contained within this framework has mobilized blood as an agent of racial exploitation and extermination.

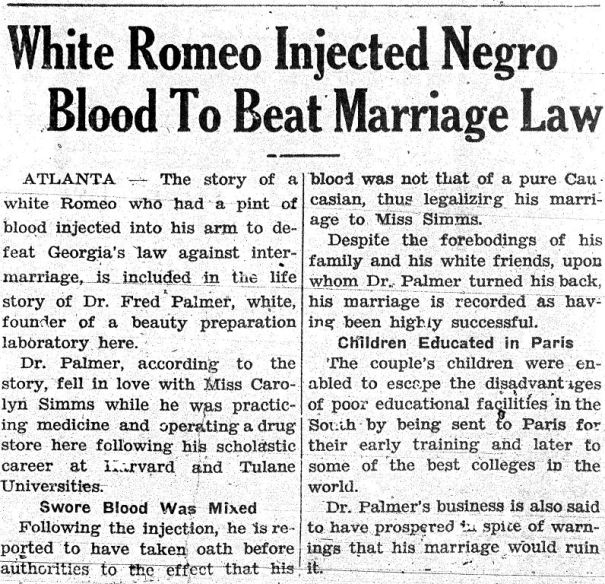

The notion of blood as a carrier of social, emotional, and intellectual worth through race was instrumental to the operation of slave society in America. Invocations of blood historically served to quantify Blackness and Whiteness, and systems of racial classification contributed to structural oppression, informing citizenship and basic rights.

Such notions continued to rhetorically and materially uphold anti-Black racism long after abolition. African-Americans were routinely categorized by the amount of their “blood” that was considered “African”, a measurement influenced by introductions of “white blood” into their lineage (with this miscegenation often perpetuated through acts of sexual violence).

During the Jim Crow era (from around 1880 to 1960), most states prohibited marriage between a “white person” and “a mulatto or person having one eighth or more of Negro blood”.57 Contemporary critical race scholars continue to explore the “one drop rule”, by which “anyone with a visually discernable trace of African, or what used to be called ‘Negro,’ ancestry is, simply, black”.58 In the structural oppression of African-Americans we see the potency of blood language as a determinant of lived and material experience.

Ideas around blood as an essential carrier of racial superiority and inferiority similarly propelled genocide during the World War II. Hitler’s racial conquest was rhetorically upheld by the violent defense of German or “Aryan” blood” While the term Aryan technically refers to a group of languages and not to people or nations, it was mapped onto notions of purity, nationhood, and whiteness.

To have Aryan blood meant that one had pale skin, blond hair and blue eyes, and non-Aryans were construed in Nazi Germany as impure and variably evil. Hitler became obsessed with “racial purity” and used the word Aryan to describe his idea of a “pure German race.” He argued fiercely for the superiority of the Aryan “race” and systematically confined, tortured, and murdered millions of people with “impure” (non-Aryan) blood.

As is the case across linguistics, any sense of neutrality related to blood language is illusory. Blood as substance or semiotic unit does not inherently mean identity, race, gender, culture, or citizenship. These associations, like all language, have developed through repetition and over time, here with material and sometimes lethal implications. De-naturalizing the link between blood and its colloquial referents allows us to uncover its ideological functions and effects.

Bloodbath

Cultural imaginings of war have long invoked imagery related to blood to reflect the tremendous loss of life wrought by conflict. “The tree of liberty,” said Thomas Jefferson, “must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” In 1913, a war enthusiast penned an essay for Life magazine in which he wrote, “War… causes the blood of the young to tingle so that they do the bidding of other, craftier and wiser men, and shed that blood so that these older, craftier and wiser may profit. Patriotism of this sort is a wonderful and essential thing in a Nation.”59 In 1921, the US Supreme Court proclaimed: “They (soldiers) pay the cost of war with their blood and their lives, and what is the greatest sacrifice of all, with the blood and lives of their loved ones.”60 During D-Day, about 4,000 men were killed or wounded on Omaha beach. The beach ran red with blood, earning it the grim name “Bloody Omaha.”

The word blood is often used metaphorically to describe wartime circumstances. “Chinese blood continued to flow after the Japanese surrender,” wrote an author in a piece for the New Yorker on the second world war in Asia, referring to the resumption of civil war between Nationalists and Communists in China.61 Soldiers in the Crimean war were “up their elbows in blood.”62 Churchill famously declared to his cabinet in 1940, “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.” In these examples, the use of the word blood objectifies violence and death, rather than animating the suffering and dying of actual people (someone’s brother, or someone’s son). When it comes to building and reinforcing patriotism and war effort support through language, the substitution of the word blood for the harrowing suffering of individual humans may serve a protective function to depersonalize and sterilize the narrative.

And the stripped-down narrative – with blood as euphemistic protagonist – has widespread appeal. A brief perusal of war literature reveals many examples of book titles that contain the word “blood”: Sealed with Blood War, Sacrifice, and Memory in Revolutionary America; Blood, Oil and the Axis: The Allied Resistance Against a Fascist Sate in Iraq and the Levant, 1941; The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War; Treaties, Trenches, Mud, and Blood – A World War I Tale. Titles help sell books, and the frequent appearance of blood on the front cover of these volumes cannot be an accident.

It is hard to imagine any publisher of a war book preferring a title that describes spilled guts, decapitation, or dismemberment. After all, this isn’t Hollywood or the boxing ring. This is the ‘real deal’. Perhaps we have a need to insulate ourselves if we are to scratch the surface and explore the subject with purpose. As a word that has both positive and negative meanings, and is familiar to every one of us, blood may provide a convenient aid or tool for navigating narratives of unspeakable tragedy.

Conclusion

In prehistoric times, blood was seen as seen as a life force. We did not really begin to understand the function of blood until the 1800s. So for tens of thousands of years, we were left to our imagination, and it is this imagination that has shaped our concepts of blood through the millennia.

Many of these ideas arose independently. For example, the practice of bloodletting spans all human eras, as do blood taboos. Attitudes towards menstruation are an example of behavior that connects prehistoric man with popular culture. Something about blood evokes near-universal reactions, as though we are somehow bound by immutable, cultural blood laws.

But then again, there are also interesting differences in blood concepts across time, and geographically. As just one example, some groups of individuals follow blood taboos while others consume blood for dietary or spiritual reasons. The existence of distinct blood practices between different people suggests that they are shaped, at least in part, by the contingencies of cultural and societal peculiarities.

This is important, because it suggests a certain fluidity or flexibility in the tapestry of blood concepts whereby cultural reactions or behaviors towards blood that are unhelpful or harmful, may be changed. We may never rid the entertainment world of blood sport and horror movies. But, as discussed earlier, efforts to encourage explicit communication about menstrual blood loss have reached the level of large-scale advertising. Though time will tell, there is hope that such strategies will minimize the shame associated with periods.

Blood is pervasive in body and mind. As substance, it is hidden from view, concealed within skin and flowing in veins. As symbol, it looms large as a fantastical construct whose meaning mutates at the whims of our imagination. We don’t talk about spleen sacrifice or liver bonds. There are no poppies decorated with the color of the pancreas. Blood occupies a privileged place in the hierarchy of body organs and tissues, inexorably woven into society in ways that transcend time and culture.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Alison Aird for her invaluable input and editing, and Marianne Grant for reviewing the final draft of the manuscript.

About the author

William C. Aird received his MD from University of Western Ontario. He completed a fellowship in Hematology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School in Boston and is presently a practicing hematologist at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. He is founder and Executive Director of The Blood Project. Click here to learn more.